The novel in verse is experiencing a bit of a renaissance in children’s and YA literature. Writers including Kwame Alexander, Elizabeth Acevedo, Jason Reynolds, Candice Iloh, Jasmine Warga and Joy McCullough have garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success. These two YA novels feature teenage narrators for whom the carefully chosen words of poetry hold the key to self-discovery.

The title and cover of Tina Cane’s first YA book, Alma Presses Play, set the scene immediately: Portable cassette players and big headphones are the technology of the day as 13-year-old Alma and her Jewish Chinese family ring in the new year of 1982 in New York City.

For Alma, eighth grade and the following summer are a time when “there’s a lot going on / but also nothing at all.” She ponders her possibly romantic feelings for her neighbor Miguel, gets her first period, dodges her parents’ increasingly frequent arguments and misses a friend who moves away. Along the way, Alma’s guidance counselor, Ms. Nola, encourages her to write down her feelings about race, gender and life in her neighborhood. Plus there’s candy to eat and share—Tootsie Rolls and Pop Rocks and Twizzlers—and music for every mood, from Stevie Wonder and Blondie to David Bowie and the Pretenders.

The most noticeable feature of Alma Presses Play is the way Cane arranges Alma’s words on the page. Most lines consist of blocks of words set apart by white space, which allows readers to inhale between each phrase and makes Alma’s words feel breathy, immediate and authentic. Lists, letters, dictionary-style definitions and outlines break up the pace. Cane sprinkles in details of life in the 1980s such as mixtapes, Atari video game systems and Judy Blume novels, as well as the ever present question of what, exactly, the plural of Walkman is.

The Greek and Roman mythology that Alma studies in school—especially the character of Janus, the god of transitions, and stories of female protagonists such as Helen and Pandora—provides an ongoing lens through which Alma makes sense of her life. Cane offers multiple, sometimes contradictory versions of these myths, enabling Alma and the reader to wrestle with the stories’ alternating messages of women’s power and powerlessness. “Even though fiction is made-up / it contains a certain kind of truth," Alma muses, a fitting description of Cane's writing. As Alma makes decisions about school, relationships and even the city she wants to live in, it’s wonderful to watch her realize that she can set her life to the music that she chooses.

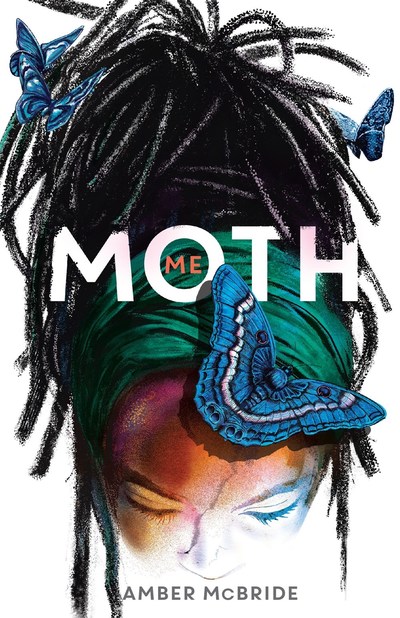

Two years ago, Moth’s parents and brother were killed in a car crash, leaving an emotionally and physically scarred Moth to live with her aunt. Despite being an elite, talented dancer, Moth vows that she will never dance again: It “feels too joyful, too greedy now.” Moth wishes that she had learned more Hoodoo practice from her grandfather, who promised before he died that he would “never leave [her] trapped—defenseless.”

None of the other Black kids at her mostly white school want to be friends, but soon Moth meets Sani, who also feels out of place living with his mother’s white family after his Navajo father left, and whose depression stops him from singing and playing the music that once brought him joy and meaning. Together, they depart on a cross-country road trip, visiting historical sites where enslavement and genocide underly white prosperity, exploring moth-related metaphors for growth and maybe even starting to fall in love. Will they find the courage to break out of their cocoons and emerge in new forms?

If you think you know where this story is going, think again. Me (Moth) will surprise you.

As in Alma Presses Play, the placement and alignment of words on the page plays a key role in the storytelling of Me (Moth). Line spacing varies, and some lines are only one or two words long. Even punctuation is unusual: Ampersands replace standard conjunctions, and names often appear in parentheses even when meanings are otherwise clear (“my aunt (Jack)” or “my mom (Meghan)”). Author Amber McBride rhymes occasionally (“the accident that split / our car like a candy bar”), drawing attention to the sounds of words, and her imagery is often tactile and tangible (“the choreography is choppy water instead of wind blowing / through a field of wheat”).

Moth engages in Hoodoo practices like lighting candles, burying significant objects and leaving offerings of food to ancestral spirits in the hopes of shifting odds in her favor. She also matches Sani’s Navajo creation stories with traditional Hoodoo stories of her own. “All stories have ghosts,” Moth tells Sani, and she’s right. In this brilliant novel, the past haunts the present in places where history, memory and spirituality intertwine.