“For decades, I wrote adult novels advocating for race, class, religious and gender equity. I write for children now. I believe they are our best hope for a better world.”

The heightened national awareness of police brutality's effects on American minorities has brought a wave of brilliant, devastating novels for teen readers like The Hate U Give and Tyler Johnson Was Here. Award-winning author Jewell Parker Rhodes’ (Sugar, Bayou Magic) Ghost Boy, which follows a 12-year-old boy named Jerome as he navigates the afterlife following his death in a police shooting, is one of the first books to breach this sensitive, necessary topic for younger readers. Here, Rhodes opens up about motherhood, the legacy of Emmett Till, the importance of honesty in stories for children and the issues of racial and social justice that fuel her writing.

I was born a year before Emmett Till was murdered, and I still recall seeing images of his mutilated body in Jet and Ebony magazines. I grew up with images of men lynched—one that still haunts me had corkscrew holes all over his body. I was raised in a segregated ghetto in Pittsburgh, where no one shielded children from racist actions and images. I watched civil rights battles and cheered Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. I believed during my lifetime, a time would come when people were judged “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” I married Brad, a white man, in Maryland (a state that didn’t recognize interracial marriages until 1967). We had a son with brown skin and a daughter with white-toned skin. And within our own family, we experienced how the world treated our children differently. Our daughter was given the “privilege” of being white, and I was considered her nanny. Our son, the older he grew, was seen as more suspect, and his father was presumed to have adopted him. Dozens of strangers declared there was no way our daughter and son could be siblings.

Rodney King was battered when our son was 2. I wrote an essay, “Evan,” for Between Mothers and Sons: Women Writers Talk About Having Sons and Raising Men, that spoke of our family’s anguish that 2-year-old Evan—who loved Legos and ants—would one day as an adult be stopped and attacked by police. When the officers who beat and hog-tied King were acquitted and the LA riots began, our family drove north—as far as Monterey Bay—to find a refuge.

My son heard my worried “walking, talking [and] driving while black” speeches. But as a high school student when President Obama was elected, Evan believed his mother, in particular, was too traumatized by past racial woes. However, as a graduate student stopped almost daily by police, he learned how some systematically devalued him and doubted he knew “his lowly place” as a black man. The constant harassment was horrific. More horrific were the numerous contemporary media examples of police officers who brutalized and killed black men across America.

I thought the world had gotten better, more tolerant. Now, as a grandmother, I worry racism and racial bias are again tearing our nation apart. I worry that my generation lost the battle for more tolerant hearts and minds. I worry that my children and grandchild have to fight and struggle on for equity and social justice.

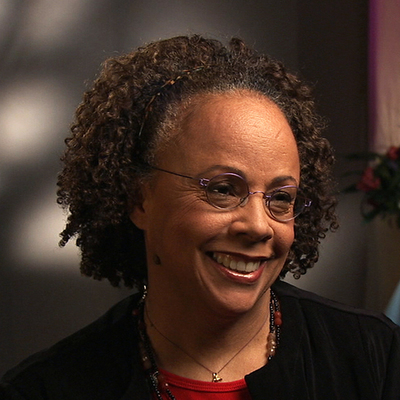

For decades, I wrote adult novels advocating for race, class, religious and gender equity. I write for children now. I believe they are our best hope for a better world. The young are curious and have such open hearts. I write challenging stories not to embitter them but to empower them to “be the change,” to remember always the sense of justice and fairness they knew instinctively as children when they become adults. Writing stories about ending all forms of bias and discrimination, I hope will be my legacy—my own personal attempt to “bear witness” beyond the grave.