Linda Spalding—who has lived in Canada for 30 years—has written fiction and nonfiction over her long and varied career. With her third novel, The Purchase, which won Canada's 2012 Governor General's Award for Fiction, she draws from her own family history for the very first time. It's the story of a Quaker man who moves to Virginia in 1798 and finds his abolitionist principles tested by the reality of the slave economy. In an exclusive behind-the-book story, Spalding writes about her discovery of this story and how it inspired this poignant historical novel.

My grandfather’s grandfather left an established life in Pennsylvania with a wagon full of children bound for the far western edge of Virginia. The year was 1798. When he finally stopped at the edge of what was then the United States, just a few miles from the Cumberland Gap, he erected a small cabin, the pieces of which still lie scattered on the ground of Jonesville, Virginia.

Daniel’s migration brought wealth to the family but it cost us everything we valued.

As a child, this story struck me as wildly adventurous, but also troubling. What father would take such risks? How long was the trip? Was it cold? What did they eat? And why had they left? What was wrong with life in Pennsylvania? “He was disowned by his community,” my father admitted once over his nightly highball. “He was sent off into exile!” I learned that Daniel Dickinson, this migratory ancestor, was a Quaker, one of those good people of strong moral purpose and fervent belief who began abolitionism. Therefore, my father’s next admission horrified me. “We didn’t stay long in the south,” he said. “And we freed all our slaves before we left.”

My father was a civil rights lawyer and I had always maintained absolute faith in our familial virtue. Old Daniel a slave owner! What eclipse of honor could have brought him to such a choice? What must he have felt when he first raised his hand at an auction in order to buy a human being? How did he live with his very well-developed conscience after making that unconscionable choice? I think the puzzle of this must have nagged at me for many years as I became more and more interested in Quakerism, participated in meetings of worship and made a pilgrimage to early Quaker sites with a group of international students. Never were there people of sturdier ethical fabric than the early Quakers.

Then I was given the genealogy a paternal aunt had carefully prepared and found part of an answer. Daniel Dickinson had lost his first wife in childbirth and quickly married a Methodist. That was all there was to the exile. Needing a mother for his many children, he must have felt desperate. Then, shunned for marrying outside the faith, he had packed his family into a wagon and driven them to the edge of the world. And there, in that wilderness, he had found dilemmas insurmountable.

I made a journey by car along the route Daniel took when he left Pennsylvania, and by the time I reached the little spot in Virginia where he finally pulled to a halt and unloaded his family, I began to understand. In 1798, there was no town in that wild place. There was a bit of land he could have in exchange for one of the warrants he’d brought from Pennsylvania. Land warrants, these were, given to veterans of the war with King George. How did Daniel come by them? He had certainly never fought. He was a pacifist, and anyway too young for that war. The warrant he exchanged for his first six acres was worth $50. I was able to find the deed and other documents in the courthouse. With children too young to help him farm, he needed a worker. And there was no paid labor to be had.

I stepped over the stones of his fallen chimney and saw, adrift in the grass, three graves. I saw the pretty creek and the mansion his son had built in 1830, every red brick of which had been molded by slaves. What must have been the reaction of those children who had been brought up so diligently, torn from their home, and brought to a place where their father lost his way? Daniel’s migration brought wealth to the family but it cost us everything we valued.

For a novelist, all of it had to be imagined and felt right down to the bones, remembering that class and race and religion determined everything in 1798. The smallest differences caused distrust, hostility and violence. And when you migrated from one place to another, social signals were often impossible to navigate. Quakers. Methodists. Africans. Confederates. There was all of that to understand. But grief and shame and envy have felt much the same to everyone in every time. My characters were waiting in the yellowed pages of that genealogy with their passions and their frailties, their crimes, their secrets and their sorrows. Each of them had a story to tell.

There were many things I liked about my Grandmother Puffer’s home: cartoons on television (We didn’t have a TV at home: hippie parents.), Cheerios for breakfast (ditto), and all manner of ancestral relics. There was a genuine family tree—branches wider than my arms—and artifacts like a chair that Myles Standish had sat in (and in which we were not to sit) and a bugle that had been played at President Wilson’s inauguration. More than all this stuff, there were the tales my grandmother could tell.

There were many things I liked about my Grandmother Puffer’s home: cartoons on television (We didn’t have a TV at home: hippie parents.), Cheerios for breakfast (ditto), and all manner of ancestral relics. There was a genuine family tree—branches wider than my arms—and artifacts like a chair that Myles Standish had sat in (and in which we were not to sit) and a bugle that had been played at President Wilson’s inauguration. More than all this stuff, there were the tales my grandmother could tell.

A single act of defiance from a daughter. An impulsive decision from a father, made in a burst of anger. A life changed forever.

A single act of defiance from a daughter. An impulsive decision from a father, made in a burst of anger. A life changed forever.

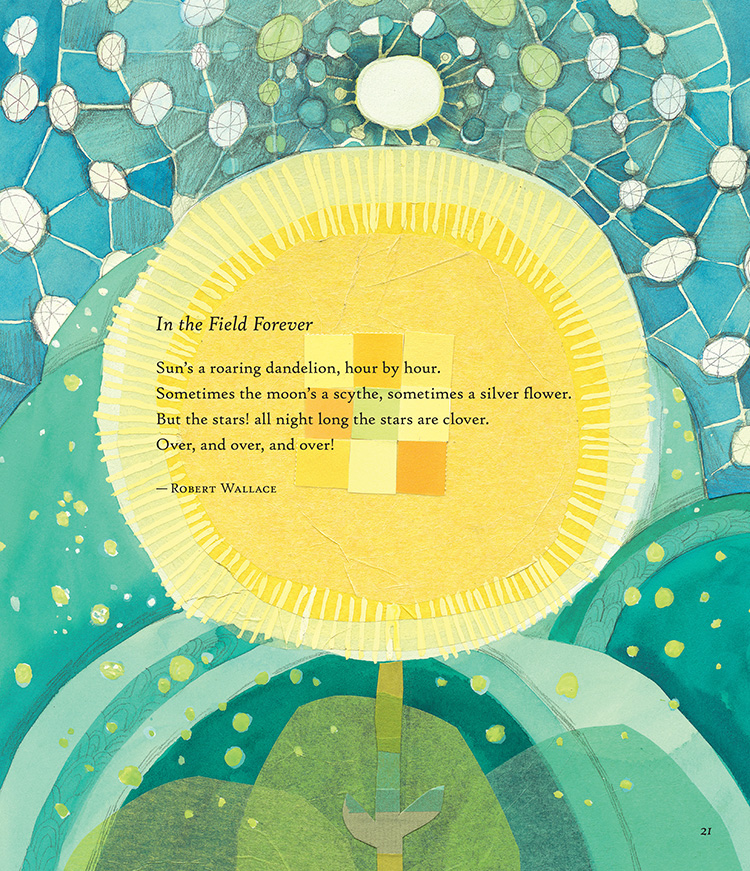

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

In 2002, I took my first trip to Kabul, Afghanistan. I was accompanied by my parents, who had left the country in the early 1970s, a peaceful and progressive time in the nation’s tumultuous history. We reunited with family, explored conditions of local hospitals and searched through piles of rubble where a family home once stood. It was a bittersweet experience for us all, especially my parents, who often felt foreign in their own homeland. This was not the country they had left behind. The decades of war in Afghanistan set the nation back in a devastating way. My mother and her sisters all attended college and worked alongside men in the airline industry, international organizations and engineering companies. From what we have seen on the news in the last few years, it is hard to imagine such an Afghanistan ever existed.

In 2002, I took my first trip to Kabul, Afghanistan. I was accompanied by my parents, who had left the country in the early 1970s, a peaceful and progressive time in the nation’s tumultuous history. We reunited with family, explored conditions of local hospitals and searched through piles of rubble where a family home once stood. It was a bittersweet experience for us all, especially my parents, who often felt foreign in their own homeland. This was not the country they had left behind. The decades of war in Afghanistan set the nation back in a devastating way. My mother and her sisters all attended college and worked alongside men in the airline industry, international organizations and engineering companies. From what we have seen on the news in the last few years, it is hard to imagine such an Afghanistan ever existed.

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.