The harrowing and horrifying stories of human trafficking are not something we necessarily want to read—we would like to believe that we live in a world without slavery—but they are stories that need to be heard. In her powerful book Breaking Free, Abby Sher has collected the true stories of Somaly Mam, Minh Dang and Maria Suarez, three women who survived servitude and have become leading activists in the anti-trafficking movement. Sher shares a story from the research for Breaking Free, when she met Minh Dang, whose abuse occurred in a quiet suburb of California.

The harrowing and horrifying stories of human trafficking are not something we necessarily want to read—we would like to believe that we live in a world without slavery—but they are stories that need to be heard. In her powerful book Breaking Free, Abby Sher has collected the true stories of Somaly Mam, Minh Dang and Maria Suarez, three women who survived servitude and have become leading activists in the anti-trafficking movement. Sher shares a story from the research for Breaking Free, when she met Minh Dang, whose abuse occurred in a quiet suburb of California.

If I were a trafficking survivor, I wouldn’t trust me either.

I used to write sketch comedy for a living. I have been known to tweet about potty training my toddler. Why was I calling Minh Dang—survivor, activist and recently named a "Champion of Change" at the White House—to chat about her experiences?

Because once I heard her story, I couldn’t unhear it.

We both grew up in neat houses with rose bushes in our front yards. We both loved peeling off dirty shin guards after a soccer match. We both collected stickers and stationery.

The only thing was, at night, Minh’s parents were molesting her from the time she was 3 years old. Then selling her body at a local café. She was enslaved and/or abused by them for 17 years before she was able to break free.

Before I dialed her number, I read all of her blog posts for Don’t Sell Bodies. Then I reread them, studying her every comma or question mark. I felt like she was in the room, sitting next to me. Everything she shared was so vivid and intimate. When she wrote about rehumanizing survivors, or finding ways to relate to even her perpetrators, I thought, This woman is a superhero.

Then I read her next piece, which said, Don’t call me a hero. Call me human.

Easier said than done.

It’s so hard for me to talk to someone I admire without getting stammery and silly. If I see a celebrity of any kind, I usually blush or pretend there’s something super interesting about the floor. With Minh, I knew that would be kind of an insult to idolize her, because what she was writing was all about our collective humanity.

Lucky for me, she sent me a message that she was going through a rough time and needed to cancel our phone date.

I wrote back saying that I was here, and I only wanted to help, not to pry.

An hour later, we were on the phone, both feeling a little raw and shaky.

We talked about the weather. We talked about our favorite color. We talked about comedy clubs and dating and yes, I even mentioned potty training.

When I hung up I felt giddy, like I had a best-friend crush.

A few weeks later, I was walking up to her cottage in Berkeley, California. It was one of those so-perfect-I-have-to-pinch-myself days where the sun and the blooming flowers were laughing out loud.

I knew from pictures that Minh was naturally beautiful, but even more so in person. She had dark, intense eyes and a short bob framing her face. No makeup, but long hoop earrings glittered when she spoke. She immediately invited me to sit on the couch together, and we just started gabbing. She asked me how my flight was and offered me some frittata. I couldn’t help it—I asked her if we could be best friends. (She still hasn’t answered me on that one yet).

Over the next two hours, Minh taught me the most important lesson ever (no offense to all my great teachers and mentors through the years.): We are all human. We are all the same. So as Minh says, the first step in making a real change in anti-trafficking starts with self-love. To believe in Minh is to believe in humanity.

Each of the women in this book is astoundingly brave and fierce. They are also incredibly human. And somehow, they trusted me. It was an honor to write their stories.

Thank you, Abby!

Some people say that certain songs remind them of a time in their life. For me, it’s each of my books. When I started Still Missing I was in a transitional stage, not happy in my career, my relationship or my house. I started writing the book on my old computer in the upstairs bedroom of the character home I owned. The temperature was inconsistent, and I was either too cold or sweltering in the summer. Six months later, I sold that house, and continued writing in the office at my townhouse. I can still close my eyes and see Post-it notes stuck all over the wall from when I was mapping out the sessions.

Some people say that certain songs remind them of a time in their life. For me, it’s each of my books. When I started Still Missing I was in a transitional stage, not happy in my career, my relationship or my house. I started writing the book on my old computer in the upstairs bedroom of the character home I owned. The temperature was inconsistent, and I was either too cold or sweltering in the summer. Six months later, I sold that house, and continued writing in the office at my townhouse. I can still close my eyes and see Post-it notes stuck all over the wall from when I was mapping out the sessions.

says, her words broken up by a sharp vocal outburst, her head jerking. “Everyone was always so happy to be around me. I just don’t feel like myself anymore.” Her name is Thera Sanchez, and I first saw her on the “Today” show in January 2012, a time when she and several other female teens in Le Roy, New York—all with similar vocal tics and twitches—were appearing everywhere: the morning shows; CNN; every major newspaper and magazine. All these lovely, panicked girls begging for answers to the strange affliction that seemed to be spreading through their school like a plague. Watching them and their terrified parents, I couldn’t look away.

says, her words broken up by a sharp vocal outburst, her head jerking. “Everyone was always so happy to be around me. I just don’t feel like myself anymore.” Her name is Thera Sanchez, and I first saw her on the “Today” show in January 2012, a time when she and several other female teens in Le Roy, New York—all with similar vocal tics and twitches—were appearing everywhere: the morning shows; CNN; every major newspaper and magazine. All these lovely, panicked girls begging for answers to the strange affliction that seemed to be spreading through their school like a plague. Watching them and their terrified parents, I couldn’t look away.

No one is a villain (or a sidekick or a mentor) in her or his own story, and in my recent work I’ve enjoyed exploring well-known stories from the point of view of their secondary characters. King of Ithaka tells part of Homer’s Odyssey from the point of view of Telemachos (Odysseus’ teenage son), and

No one is a villain (or a sidekick or a mentor) in her or his own story, and in my recent work I’ve enjoyed exploring well-known stories from the point of view of their secondary characters. King of Ithaka tells part of Homer’s Odyssey from the point of view of Telemachos (Odysseus’ teenage son), and

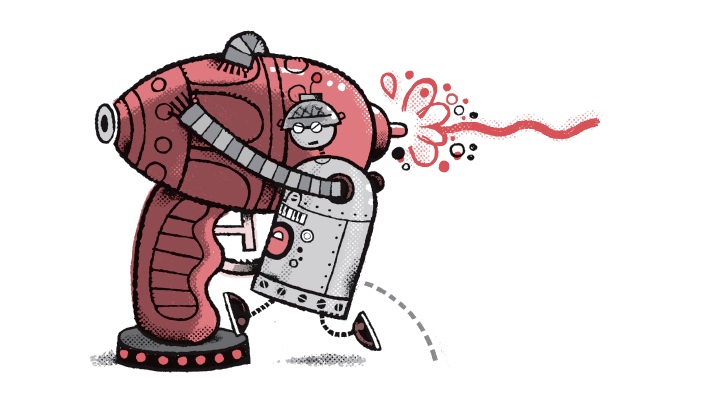

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.