Enter the glamorous (and not-so-glamorous) world of life in a band through Charlotte Huang's debut YA novel, For the Record. High school student Chelsea has just become the lead singer of the popular band Melbourne, and she's dealing with being on a bus tour with three guys, attracting the attention of heartthrob Lucas Rivers and coping with the sink-or-swim music industry.

Huang shares the backstory of For the Record and explains how her music agent husband helped structure the story and provide authentic details of life on tour.

By the time I started writing For the Record, I already had years of material to draw from. Since my husband and several of our close friends work in the music industry, I’ve listened to hours of music talk over dinners, gone to probably hundreds of shows, and chatted with and gotten to know many musicians. I felt totally confident that I could write a realistic story about a famous band on tour. However, as I got deeper into the draft, I realized that there were gaps in my knowledge that would require the help of some experts.

Tour routing

This was the easiest hurdle to overcome. Well, maybe not for my husband who actually had to do it. As a music agent, he plans tours all day long for his clients so I thought he’d be able to do it in his sleep. But according to him I tied his hands in impossible ways, worse than any real manager would—“but I want them to shoot a video before this date”; “but I need them to be in Detroit after this happens”; “are you sure they wouldn’t be able to get from here to there in just one day?”—yet somehow, Melbourne has a great tour and I’m still married!

Bus life

I’ve never had to live on a tour bus, a fact for which I am grateful. So I took a friend, who often does have to live on a bus, out to lunch. A lot of the detail and texture about noise pollution, bus etiquette and how to negotiate space come from this conversation and about a billion follow-up texts and emails. I probably owe her another lunch.

Tour logistics

While my husband books the tours, he doesn’t have to go on tour. So for this one, he was off the hook. Fortunately, I’ve killed enough time in production offices, both pre-and post-show, that I was able to base Melbourne’s tour manager’s exacting and rigid ways on firsthand observation. But to get a little more specific, I interviewed a tour manager friend.

On stage

Here was the single biggest hole in my understanding of what it’s like to be in a band. I mean, if you dangled me over a cliff and told me to route a 30-day U.S. tour off the top of my head, I could probably do better than the average person. But ask me what it’s like to get up and sing in front of thousands of people? Obviously I had no clue. So I asked one of my husband’s clients for some insight. My questions were endless: What’s the difference to you between a good show and a bad show? What goes through your head if you mess up? What do you do when one of your band mates messes up? What song do you hate? How do you feel when you have to perform it? Our conversations gave me a much more intimate appreciation of what my main character experiences during the shows.

Talking to people who live the touring life made the experience of writing For the Record much richer. And I can only hope that the same is true of reading it.

Charlotte Huang grew up near Boston, graduated from Smith College and received an MBA from Columbia Business School. She lives in Los Angeles. When not glued to her computer, she cheers her two sons on at sporting events and sometimes manages to stay up late enough to check out bands with her music-agent husband. For the Record is her first novel. To learn more, visit her website and blog at charlottehuangbooks.com.

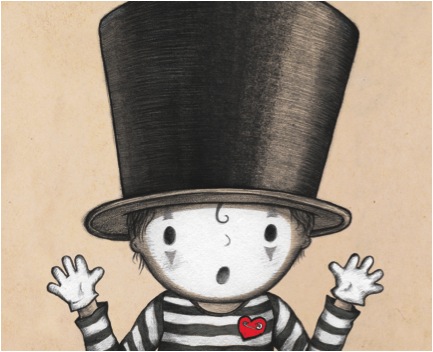

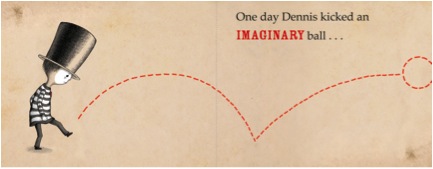

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled.

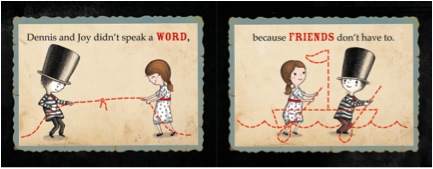

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled. On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.

On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.

We grew to appreciate his genius all over again, his unique ability to give life and concrete reality to the most extravagant story idea. There was Stuart Little, hammering the faucet in the bathroom of his family’s New York apartment. There was Wilbur the pig, turning somersaults in his barnyard, and Templeton the rat fetching Charlotte’s egg sac from the barn ceiling. There was Sailor Dog, “born in the teeth of a gale,” building himself a shelter after being wrecked on a desert isle. There was Miss Bianca, pleading with the carousing Norwegian mice to lend their help to the Prisoners’ Aid Society or coolly facing down Mamelouk the cat. There was little Laura Ingalls, skipping through the big woods, twirling her straw hat with abandon. Scores of stories and scores of memorable pictures, delighting both children and their weary parents.

We grew to appreciate his genius all over again, his unique ability to give life and concrete reality to the most extravagant story idea. There was Stuart Little, hammering the faucet in the bathroom of his family’s New York apartment. There was Wilbur the pig, turning somersaults in his barnyard, and Templeton the rat fetching Charlotte’s egg sac from the barn ceiling. There was Sailor Dog, “born in the teeth of a gale,” building himself a shelter after being wrecked on a desert isle. There was Miss Bianca, pleading with the carousing Norwegian mice to lend their help to the Prisoners’ Aid Society or coolly facing down Mamelouk the cat. There was little Laura Ingalls, skipping through the big woods, twirling her straw hat with abandon. Scores of stories and scores of memorable pictures, delighting both children and their weary parents.