There’s this thing that follows you around every day of your life if you grew up as a Korean-American kid. It invades your home every evening, it hypnotizes your parents, it is a magical link to a faraway place.

The thing is Korean dramas.

When I was a kid growing up in Los Angeles, my parents worked very hard, like a lot of immigrant parents. My dad made the hour-long trek to Long Beach at the crack of dawn to work for the Department of Defense; my mom worked so much that she would take “naps” at red lights until my sister or I poked her awake.

Hey, this was the ’80s. That kind of stuff was fine.

So, when it was evening, their escape was found in the form of dramatic yelling and crying via VHS tapes of Korean dramas. Back then, they were acquired at the local video store, a tiny hole-in-the-wall next to a Korean grocery store filled floor to ceiling with VHS tapes. The spines had titles written on sticker labels layered over previous labels. Layers because they were recorded over and over again. Sometimes you got the billionth-generation tape and had to return it because it was wobbly and unwatchable.

In my young adult novel I Believe in a Thing Called Love, the main character, Desi Lee, decides to use the “K Drama Steps to True Love” to snag her crush. When she has her epiphany, she’s surprised to see the answers in what she calls “the white noise of her life.” K-dramas were also the white noise of my life. They were always on in the background while I did homework, ate dinner or read in bed.

Because for my parents, it was their connection to Korea. Having immigrated to the U.S. right before their marriage, they were far from smoothly assimilating into American life. My mom was hesitant to complain about shitty customer service because of her poor English (which, in retrospect, was pretty good). My dad had to listen politely to my ex-military neighbor’s constant inquiries into North Korea even though he’s from the South. Both my parents reminded my sister and me, over and over again, that we were Korean. Not just American. That we should never forget it.

But when you’re an immigrant kid, you do everything to forget it. To distance yourself from that foreignness, to wriggle into your American skin. To hold your breath and hope that no one notices the whiff of Korea on every part of you—quite literally, from the scent of kimchi in your house to the way you pronounce “freeway.”

So Korean dramas were just another thing that set my family apart from others. Why couldn’t my parents just watch “Growing Pains” with me and understand it? Why were the dramas always so melodramatic and loud?

I’m not sure when I made the turn from resenting K-dramas to enjoying them. I often watched them with parents even when I didn't quite like them. Try as I might to distance myself from this part of my parents, I also felt a familiarity with the people on screen that comforted me. And so I began to like them. And when I was in high school, I had a group of Korean-American friends and we started watching the “cool” ones in earnest.

Years later, I would download them illegally during my freshman year of college. I only moved two hours south to San Diego, but they reminded me of home and I would stay up late into the night watching them, willing away my homesickness. When I moved to Boston, a city so homogeneous that it was disorienting, I found a video store renting out DVDs of K-dramas near my apartment in Brighton and would trek there in the snow so that I could wrap myself up in that white noise.

In my book, Desi uses K-dramas as a map to true love. In my life, K-dramas are always a map back home.

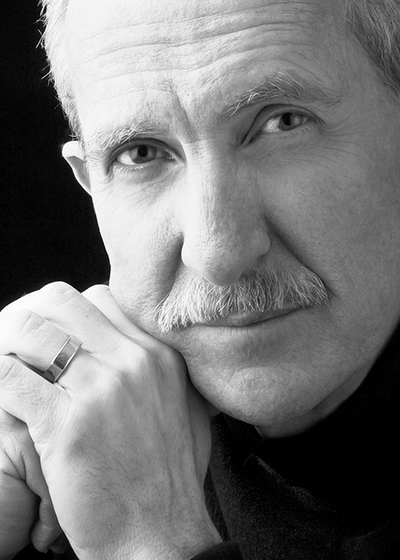

Maurene Goo grew up in a Los Angeles suburb surrounded by floral wallpaper and piles of books. She is the author of Since You Asked . . . and I Believe in a Thing Called Love and has very strong feelings about tacos and houseplants. You can find her in Los Angeles with her husband and two cats—one weird, one even more weird.