Bake

Though he’s best known as the “Great British Baking Show” judge with an icy blue stare fit to scare any hopeful contestant, Paul Hollywood is also an exceptional baker in his own right. With BAKE, he shares his go-to recipes for all the classics, from cakes and cookies to doughnuts, pastries and pies. There is, of course, an extensive chapter on bread in which Hollywood really shows off his expertise.

Chetna’s Easy Baking

The latest offering from beloved 2014 contestant Chetna Makan includes over 80 recipes for sweet and savory bakes. Chetna has always been known for her flavor combinations, and Chetna’s Easy Baking showcases this skill with mouthwatering offerings like pear, chocolate, star anise and hazelnut tarte Tatin and mini saffron vegan cheesecakes.

Simply Vegan Baking

Freya Cox made a splash in 2021 as the first contestant to create all vegan bakes. Her first book, Simply Vegan Baking, takes 70 recipes for familiar treats—such as carrot cake, cinnamon rolls and jam doughnuts—and shows bakers how to make them without eggs, milk or butter, and without sacrificing that delicious, comforting flavor.

Read our review of ‘Bliss on Toast’ by “Great British Baking Show” judge Prue Leith.

Baking Imperfect

Lottie Bedlow felt underqualified and ill-prepared for her time as a contestant on “The Great British Baking Show” in 2020. With Baking Imperfect, she vows to tell the truth about her baking struggles and imperfections so that others might feel brave enough to give baking a go. Each recipe is rated on a scale of one to five broken eggs so that bakers of every skill level will know where to start.

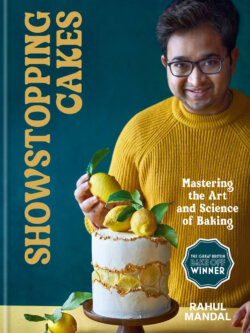

Showstopping Cakes

Winner of the 2018 season Rahul Mandal defied expectations when he awkwardly, endearingly rose to the top. His first book, Showstopping Cakes, captures the decorative pizazz he is known and loved for by breaking down each element of an eye-popping cake—from ganache to mirror glaze to marzipan—so that bakers can construct their own masterpieces at home.

Cook as You Are

Ruby Tandoh is one of the most published “Great British Baking Show” contestants, and Cook as You Are is her fourth release. This collection focuses on recipes that are easy, affordable and accessible to everyone, no matter what relationship you have to food or to your body. With recipes for whatever-you’ve-got fried rice and goes-with-everything groundnut soup, there’s truly something for every appetite and energy level.

Bake, Make, and Learn to Cook Vegetarian

Winner of the 2019 season David Atherton thinks kids should be able to whip up their own meal, snack or treat when they’re hungry. Bake, Make, and Learn to Cook Vegetarian will teach them how, with adorable illustrations by Alice Bowsher that break down each step of the process for creating vegetarian stir fry, cheesy rabbit crackers, jam tarts and more.

Giuseppe’s Italian Bakes

When Giuseppe Dell’Anno won the 2021 season, fans everywhere shouted “Saluti!” Now he’s packed all his favorite home bakes, inspired by his dad’s recipes and notes, into Giuseppe’s Italian Bakes. From polenta sponge cake to panna cotta and focaccia, every recipe is rustic, delicious and authentically Italian.