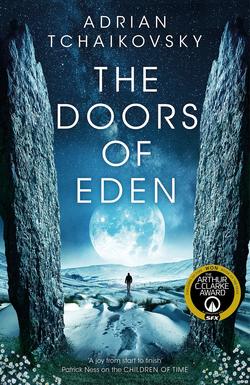

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s latest idiosyncratic novel leaps easily from the micro to the macro, beginning with two cryptid-hunting friends and expanding to encompass an entire alternate history of the development of life itself. Through it all, Tchaikovsky’s irrepressible wit and effervescent intelligence serve as lifelines for the reader as The Doors of Eden take them on a truly unique and fantastical ride. We talked to Tchaikovsky about crafting his latest awe-inspiring trip through space and time.

You excel at creating a tone that bounces between humor and horror. How do you strike that balance as a writer?

That’s kind of you to say. I suspect the rather appalling truth is that while I’m aware of various things that horrify others, they don’t necessarily horrify me in the same way. The human-spider interactions in the middle of Children of Time, say, or certain adventurous scenes in its sequel, aren’t written as horror, because they’re written from the point of view of the thing that horrifies, rather than the beneficiaries of that emotion. That discontinuity also tends to produce the horror, and the incongruity of the horror makes the humor, and the humor makes the horror that much worse.

You dreamed up a menagerie of beasts both small and large for this book. Did you scrap any concepts for other life-forms from the great beyond? Care to share any?

There’s the whole of evolutionary creation to plunder. I’d have liked to do more with anomalocarids and other Cambrian explosion fauna, because a real seed for this book was Stephen Jay Gould’s Wonderful Life, which includes a detailed description of the mainstays of that fossil biota. And I leave large gaps—there’s about a hundred million years of dinosaurs I never touched, mostly because dinosaur speculative evolution is one of the more common areas of thought. And it might have been fun to depart further from current evolution—have some wild card rise to dominance in a later era, such as a tertiary invertebrate, or late birds or fish. Most vertebrates are teleost fish after all and there’s no reason why they couldn’t have a resurgence. However, having a narrative that follows each “new” group from when it made its grand mark in the fossil record is probably easier for the reader.

“. . . to expand the mind with grand ideas is a great thing.”

The relationship between Lee and Mal anchors the book. What characters or people did you draw from, even informally, when shaping their relationship?

I think I drew a little from a lot of people to construct the pair of them. Mal is very much based on an old live-action role-playing friend of mine, plus a few other people. Overall, they are each about 50% made up and 50% stitched together from many, many friends and acquaintances.

Julian’s character shows the potential effects of understanding more than we ever wanted to. Do you think most of us are unready or unwilling to have our worldviews totally turned upside down?

I think most of us would be just as lost as poor Julian is, but you can never know until it should happen. A lot of portal-fantasy/science-fiction characters, having gone through the mirror, display a sang-froid about the whole business that I know I wouldn’t. I can certainly think of a few people of my acquaintance who I feel would be absolutely in their element if they woke up in another world.

A phrase that kept playing in my mind while reading was the phrase "a sense of wonder." Does that phrase ring true to you when thinking about this book?

A phrase that kept playing in my mind while reading was the phrase "a sense of wonder." Does that phrase ring true to you when thinking about this book?

Absolutely, yes. The whole book is kind of a background hymn to the wonders, not of any particular imaginary world, but the actual real world, past and present, which we so often take for granted. Life (back me up, Sir David Attenborough) is so varied and so intricate and so beautiful, and we waste a great deal of it. And beyond that, yes, I think a sense of wonder is an integral part of a certain kind of science fiction—to expand the mind with grand ideas is a great thing.

I found myself completely riveted by the interludes from the fictional book within this book, Other Edens. How did these fit into your plan for the story? Did you want to use such a structure from the beginning?

Honestly, I had to practice a great deal of discipline to bring them down to just what’s in the book! The interludes and their thought experiments are absolutely the inspiration for the book, without which it wouldn’t exist. And of course, many of them provide the useful background on what is going on, which would be cumbersome to try and insert in the actual text, but many others are just there for the hell of it, to show the myriad variety of the worlds I’m presenting.

In a lot of ways, The Doors of Eden challenges us to think about what we don't know or see in the world around us. What frontiers in science do you think hold the most promise for opening our eyes to something important that was there all along?

If we achieve anything like a real artificial intelligence (not just a complex algorithm that can learn how to fake being people) then that should show us a great deal about how we ourselves think, and might also find a lot of priceless but unintuitive solutions to other problems we have, in that way that computers sometimes can. Similarly, if the recent discoveries on Venus lead to the discovery of actual extraterrestrial life, that would teach us so much about the possibilities of evolution and biology in very non-Earthlike conditions (or in the buried oceans of Europa, say, or some other place within the solar system—or even an exoplanet, although that has its own raft of practical issues).

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our starred review of The Doors of Eden.

When you think back to writing this book, are there passages that you remember writing more vividly than others?

The museum sequence, frankly, was an absolute bear. I rewrote it several times over, and ended up breaking it up a lot between the characters to try and tame it. So, I remember that vividly enough, for all the wrong reasons. Beyond that, my chain of evolutionary logic that led to immortal giant trilobites is something I’m pretty damn proud of. . .

If you could dream up another Earth, a unique paradise just for you, what would it look like?

I wanted to make some cheap joke about having lots of legs and a warning that it contains spiders, but honestly I think what my perfect paradise would have would be variety—multiple viewpoints, multiple minds, complexity built of diversity. And not in danger of being extinguished by monstrous short-sighted greed, for preference.

A lot has been said about how history repeats itself and we're doomed to relive our mistakes over and over. Does that idea ring true for you when you think about Kreya and the gang?

A lot has been said about how history repeats itself and we're doomed to relive our mistakes over and over. Does that idea ring true for you when you think about Kreya and the gang?