Young adult books shine when they speak to the challenges faced by teenagers as they mature to adulthood. These three novels represent characters who experience mental illness, which impacts as many as one in six people between the ages of 6 and 17 in the United States each year. The books themselves span a range of genres and formats—one is a romance, one a graphic novel, another paced like a thriller—but each puts a face to mental illness and addresses teen mental health with the gravity and honesty it deserves.

★ This Is My Brain in Love

In a last-ditch effort to keep her family’s foundering Chinese restaurant afloat, Jocelyn Wu hires Will Domenici, who is looking to strengthen his resume with marketing experience, for a summer job. Over the course of one summer, the pair fall in love while dealing with mental illnesses that threaten both their relationship and the future of A-Plus Chinese Garden.

Jos’s work keeps her so busy, she hardly has time to consider her own mental health. She’s not even certain her parents, immigrants from Taiwan, even believe that mental illness is real. Jos appears outwardly hardworking and whip smart, and Will is the only person in Jos’ life who notices that she’s exhibiting many symptoms of depression. Will, an aspiring journalist from a wealthy family, experiences anxiety and panic attacks. His Nigerian mother has cautioned him about the risks of being open about his mental illness, so he stays guarded, even around Jos.

This Is My Brain in Love is both a sweet love story and a tension-packed drama that provides 101-level advice about overcoming the social stigmas and personal shame that can be associated with mental illness. Author I.W. Gregorio creates highly differentiated first-person narrative voices for both Jos and Will, and their complexity and nuance as characters add authenticity as well as relatability to the book. Their experiences also vitally widen the representation of mental illness to include teens of color and teens from immigrant families.

It’s a testament to Gregorio’s skill that by the time I finished This Is My Brain in Love, I felt like Jos and Will had become dear friends whose happiness in both life and love I was rooting for. I was sorry when their story came to an end.

The Dark Matter of Mona Starr

Mona, the teen girl in Laura Lee Gulledge’s graphic novel, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, refers to her depression and anxiety as “dark matter.” Taking the form of a black goblin that follows her around, Mona’s dark matter wreaks havoc everywhere in every aspect of Mona’s life.

When she feels well, Mona is a sweet, creative girl. But when her dark matter tightens its grip on her, she feels smothered by cruel, punishing thoughts. Gulledge’s illustrations depict Mona floating through space like a speck of dust, surrounded by thought bubbles with messages that include “You don’t matter” and “You’re no one.” It’s a pitch-perfect visual representation of the feelings of helplessness and isolation depression can cause.

Gulledge does not leave Mona to suffer in solitude, however. Throughout the book, Mona visits a compassionate therapist who coaches her (and readers) on how to corral negative self-talk and reframe harmful stories. Featuring chapters titles like “Notice Your Patterns” and “Break Your Cycles,” Dark Matter is instructive about the daily coping skills that mental illness often requires.

Favoring emotional exploration over a straightforward plot, Dark Matter demonstrates through clever and heartfelt illustrations how Mona’s experiences of anxiety and depression (dis)color her world. Mona has enough self-awareness to realize that not everyone spirals into turmoil so easily, and like many people who’ve just been diagnosed with mental illness, she feels broken. However, she gradually learns that she can manage her dark matter with the help of a strong support network and by embracing effective self-care and personal creativity. Gulledge includes a self-care plan in the book’s final pages to help readers form strategies for good mental health themselves.

The Lightness of Hands

Legerdemain is a branch of magic in which the performer uses their hands to perform acts of trickery or sleight of hand; deriving from French, it means “light of hands.” As the daughter of the Uncanny Dante, a once-famous magician, 16-year-old Ellie is gifted when it comes to legerdemain and other magical techniques.

But Ellie feels uneasy about her talent. She’s seen how just one mistake can ruin a career like her dad’s, and the bipolar II disorder she inherited from her late mother can cause her to spiral after performing. But her father has heart problems and has been shunned by the magic community, so Ellie must perform—as well as pickpocket and steal—to pay their bills.

Jeff Garvin’s The Lightness of Hands spins a sprawling, elaborate story. The central narrative involves Ellie’s plan to get her father to Los Angeles to perform his infamously failed magic trick, the Truck Drop, on live TV for the first time since it went disastrously wrong. The payday from this gig could profoundly improve their lives, which would include giving Ellie reliable access to the medication she needs.

As Ellie tries to persuade the Uncanny Dante to stage a comeback, she experiences the manic and depressive episodes that define her illness. They cause her to lash out at her dad, her best friend and her maybe-boyfriend, as well as to constantly second-guess herself. Garvin, who shares in an author’s note that he also has bipolar II, vividly portrays the emotional whiplash of the disorder.

Garvin walks a tightrope between a story chock full of juicy secrets of magical tradecraft and the community of people who make their living as professional magicians and the more grim reality of Ellie’s life, which includes realistic and weighty representations of the aftermath of parental suicide as well as Ellie’s suicidal ideation and attempts. Ellie’s thoughtful reflections about her identity and experiences give the book heart, and the support system she constructs around herself give it hope. In the hands of teens who need it most, The Lightness of Hands will be a beacon beaming out the message that life with mental illness is always worth living.

Society journalism—that is, the gossip pages—doesn’t carry the same gravitas as other areas of journalism. That might change with Gatecrasher. Author Ben Widdicombe, a former gossip reporter, shares lessons about the world’s wealthiest people gleaned from attending Academy Awards parties, lunches at Elaine’s and weddings at Mar-a-Lago for the past two decades.

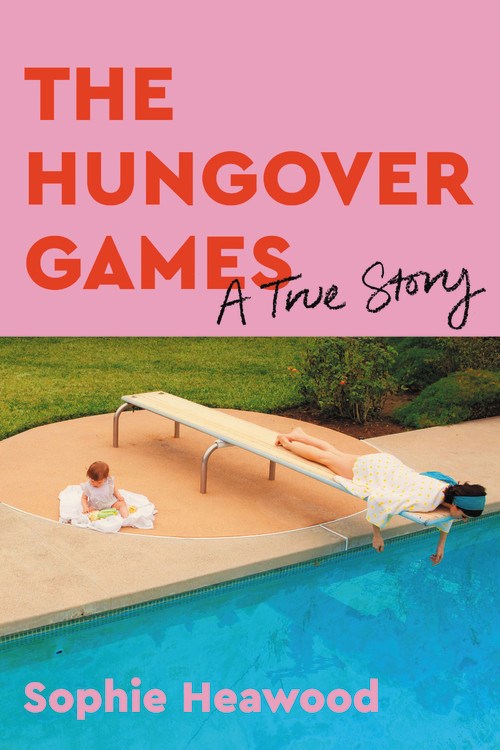

Society journalism—that is, the gossip pages—doesn’t carry the same gravitas as other areas of journalism. That might change with Gatecrasher. Author Ben Widdicombe, a former gossip reporter, shares lessons about the world’s wealthiest people gleaned from attending Academy Awards parties, lunches at Elaine’s and weddings at Mar-a-Lago for the past two decades. British writer Sophie Heawood was living her dream, working as a journalist covering the entertainment industry in LA. She wrote breezy celebrity profiles, went out every night and came home to her tiny Sunset Boulevard apartment.

British writer Sophie Heawood was living her dream, working as a journalist covering the entertainment industry in LA. She wrote breezy celebrity profiles, went out every night and came home to her tiny Sunset Boulevard apartment. Do you think helmets are for wimps and seat belts are for suckers? Is following rules something other people do? If your answer is “Hell, yeah!” then you would’ve loved Action Park, a 35-acre New Jersey amusement park that provided dangerous entertainment for 20 crowded, wild summers beginning in 1978. Gene Mulvihill was the charismatic, impulsive, creative, law-avoiding, retail magnate, millionaire founder, and Andy Mulvihill, who wrote Action Park with journalist Jake Rossen, is his son.

Do you think helmets are for wimps and seat belts are for suckers? Is following rules something other people do? If your answer is “Hell, yeah!” then you would’ve loved Action Park, a 35-acre New Jersey amusement park that provided dangerous entertainment for 20 crowded, wild summers beginning in 1978. Gene Mulvihill was the charismatic, impulsive, creative, law-avoiding, retail magnate, millionaire founder, and Andy Mulvihill, who wrote Action Park with journalist Jake Rossen, is his son.