It’s a frigid day in Milwaukee when I call author-illustrator Lois Ehlert to talk about her newest book, The Scraps Book: Notes from a Colorful Life. Not surprisingly, she is inspired.

“It is these gray winter days that stir my creativity,” Ehlert says. “I am so happy to stay in and work. I am sitting here right now with a bag of scraps on my drawing board. I have green paint underneath my fingernails. I am as happy as a clam.”

It is this abundant creativity we have to thank for Ehlert’s long list of distinctive picture books for children in a career that has spanned decades and which once began with the study of graphic design.

Ehlert’s signature collage illustrations, which celebrate color, shape and form, immediately attract the curious eyes of the youngest of readers. In 1989, she received the Caldecott Honor for Color Zoo, and in 2006 the inventive Leaf Man, a story told with real autumn leaves, was awarded a Boston-Globe Horn Book Award. Early in her career, Ehlert illustrated the perennially best-selling Chicka Chicka Boom Boom, written by Bill Martin Jr. and John Archambault.

The Scraps Book: Notes from a Colorful Life is an autobiographical picture book, filled with old family photos, bits of art, Ehlert’s inspirations, early sketches and book dummies. It is a splendid book, telling the story of Ehlert’s childhood and subsequent career as an illustrator, while also dispensing earnest yet never cloying bits of wisdom for young, aspiring artists. There is a real energy and spontaneity in Ehlert’s work, and the book captures that with style.

“It isn’t the kind of book you do when you are 21 years old,” Ehlert says. “I am not a formal person that likes to do a biography. That is not my world.”

The book was entirely her idea, not an editor’s or agent’s. “You have thoughts like this as you get older,” Ehlert explains. “I wanted to share. I do a lot of workshops with children at the art museum here. I delight in it. I need to set it down while I still have my marbles.”

Ehlert also shares photos of her personal collections in the book, everything from multicolored fabrics to folk art to ice fishing decoys. “There are a lot of things that call out to me, ‘Lois, buy me,’ ” she jokes, adding that it’s been frequent travels over her lifetime that have generated so many rich and diverse collections. “The world is full of such interesting things. I have Indian moccasins, textiles from all over the world. I have African masks, and I have pre-Columbian pots and a lot of books. I like fabric, so I have a lot of textiles with embroidery and stitching. I have pieces of clothing, children’s dresses from India, lovely things that probably will not exist in this world any longer. [They are from] a different time when people spent more time doing handwork.”

The Scraps Book is not only an affirmation of art, color and creativity, but it also serves as a touching tribute to Ehlert’s family. Raised by parents who encouraged her art—“I was lucky; I grew up with parents who made things with their hands”—she always had art supplies and tools at the ready.

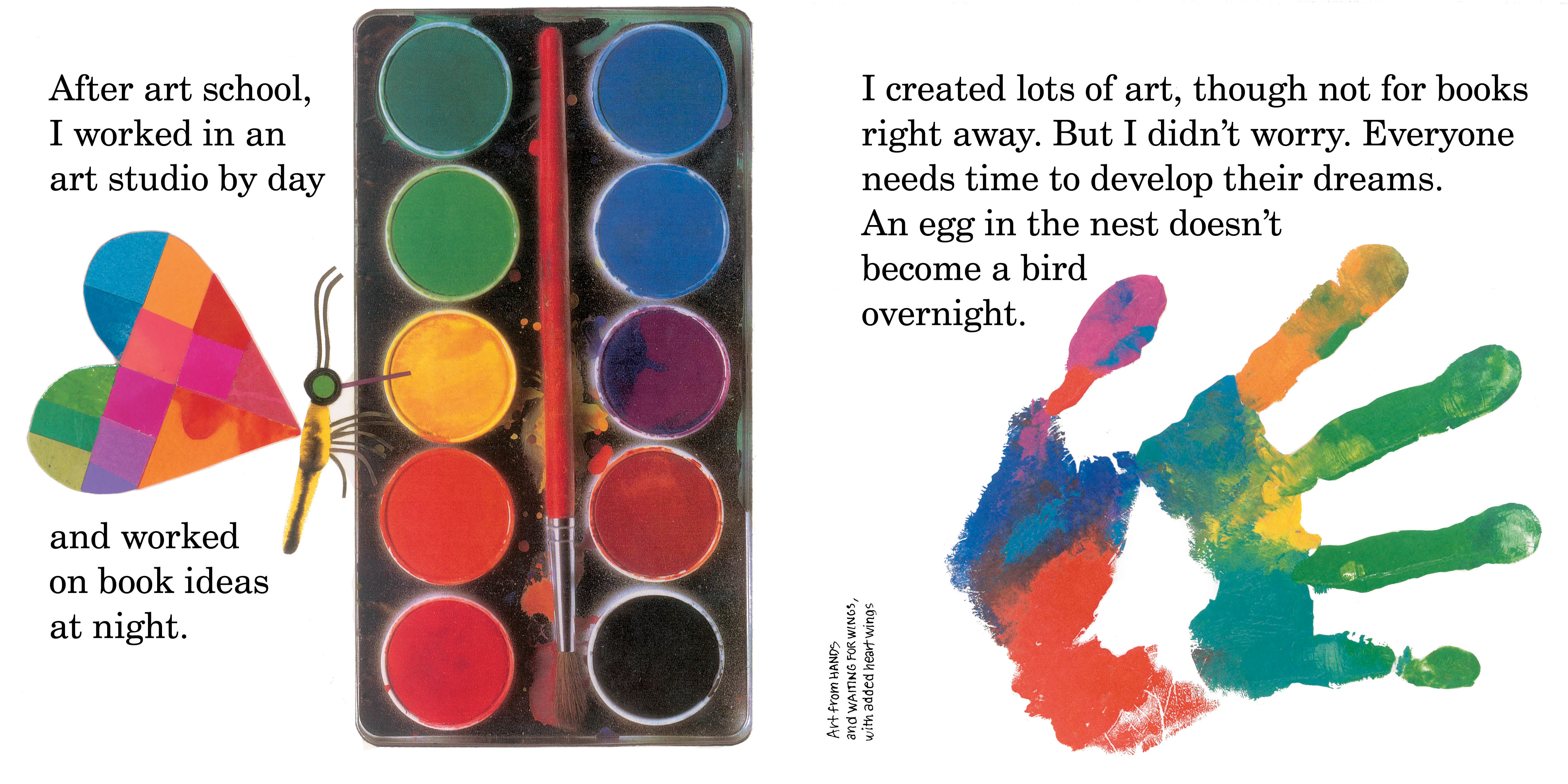

One spread features photos of her dad’s brush and her mother’s pinking shears. “It is another example of recycling,” Ehlert says. “It is [about] growing up with not much money—but a lot of spirit. I think that is also what I am trying to say. If you look at some of my books, [you see that] you do not have to go to the art supply store for everything. Look into nature.

“I asked my mother one time if she really knew what she was doing for me,” Ehlert adds. “She said no, that they just knew I was interested in [art]. Isn’t it wonderful that a parent is that perceptive?”

Nor did her parents discourage her from art school. “You would think they might, because I was the oldest of three children. How was I going to make a living, and how was it going to work out? You just have to follow your instincts. I have had other jobs, but if you love to do something, do it as well as you can.”

Find a spot for creating art, get comfortable and begin, Ehlert advises aspiring artists in the book. Oh, and don’t forget to get messy. Given that her tools are often as simple as scissors, construction paper and glue, it’s far from an intimidating notion for children, rich or poor. It’s empowering as well, one of many qualities that make this book special.

“My wish,” Ehlert says, “is that there will be little kids like I was, who read that and say, ‘Well, if she can do it, I can do it.’ It may take them 20 years. I was a relatively late bloomer.”

And it all began, as noted on the first page of The Scraps Book, with a young girl who read all the books on the library shelves and thought maybe someday she could make a book.

When I point out to Ehlert how much I love that opening, she says, “I had no clue how to do [it]. It is kind of funny, but look what happened.”

Julie Danielson features authors and illustrators at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, a children’s literature blog.

Images from The Scraps Book, reprinted with permission.