LeUyen Pham's picture book Outside, Inside addresses the COVID-19 pandemic with sensitivity and compassion for young readers. BookPage spoke with Pham, a 2020 Caldecott Honor recipient, about the origins of her project, which began as a series of sketches during the early days of quarantining at home, as well as the real-life inspirations behind the feline guide who appears on every page of her book.

Your author’s note describes how you began “sketching moments from each day” during the early days of quarantine. When did you realize that your sketches could become a book?

I had to find a way to make sense of the sudden shift of the world, and I began collecting these thoughts in my head. They sort of spilled out on paper that way. I didn’t know exactly what it was that was happening, but after creating so many picture books, my mind automatically molds thoughts into that format. Still, I don’t think I was seeing the forest from the trees yet.

Out of sheer desperation, I called my editor and told her that I had something going on in my head. I didn’t know what it was—it didn’t have a form, it was just a series of disconnected dots. I remember her explaining very carefully to me that there was a difference between communicating strong feelings and telling a strong story. She wanted me to go for it some more. I called my agent, Holly McGhee, as well, and she encouraged me to just keep putting things down, that eventually the dots would connect, that something inside had to come out and I should just let it.

I think the moment for me when I suddenly saw it as a book was when I started binding the pictures together with words. Then it became more clear to me.

“We were always writing it from the perspective of the future, struggling to make sense of this time. The wild part is that we were making sense of it while we were going through it.”

Outside, Inside balances the feelings of sorrow, fear and loss many people have felt during the pandemic with unexpected silver linings, such as moments of connection and community. Was this a difficult balance for you to achieve?

It was as difficult to achieve on paper as it is to achieve in real life. Early on, we understood that this pandemic was going to affect different people in different ways, that while for some people it would require an adjustment of working from home and balancing your family’s life with your own work, for others the change was dramatic and suddenly put their livelihoods at stake. Even to say the words “silver lining” was insulting to a large portion of the population and indicative of the privilege of the person saying it. How do you allow for moments of goodness in such dark times?

In the end, I think we were able to get away with it because the book is a documentary of sorts. It’s a collection of moments happening in real time. I recorded what I saw at the time, without fully understanding how amazing those chalk drawings and window signs and neighborhood shopping trips were. I was overwhelmed by how much community I witnessed during a time in which we were essentially ordered to stay away from communities.

When I look at the book now, there’s a rhythmic pattern in its fluctuation between sorrow and connection. I'm chalking that up to my brain going into automatic children’s book mode, my editor’s gentle guidance, my agent’s encouragement and some universal wave we were all riding. We were all looking for that balance. Drawing it into pictures just clarified it all.

When I look at the book now, there’s a rhythmic pattern in its fluctuation between sorrow and connection. I'm chalking that up to my brain going into automatic children’s book mode, my editor’s gentle guidance, my agent’s encouragement and some universal wave we were all riding. We were all looking for that balance. Drawing it into pictures just clarified it all.

One spread in the book depicts scenes in hospitals and medical facilities. Was this a difficult spread for you to illustrate? How did you decide on all of the different scenes it includes?

This was one of the most difficult spreads I’ve ever illustrated. I simply could not process what these amazing health care workers were facing in those early days, when little was understood of the virus, supplies were short and emergency workers were finding workarounds with duct tape and plastic wrap.

These groups of frontline workers absolutely blow me away. What they were and are subjected to on a daily basis, at huge risk to their own lives, all in assistance of others, is simply unfathomable to the average human. I watched news stories of nurses, doctors, EMTs and even janitors and cleaners witnessing firsthand what this virus could do, but finding humanity in these desperate situations and giving hope, kindness and connection to those suffering from a virus that isolates you at the end of life. So many interviewees likened the situation to a war zone, and I could understand why. When people complain about losing their freedoms by being forced to wear masks, I wish they would look at the cost of rejecting that minor act, at the undeniable impact on these workers and their patients who are at the tail end of that decision.

I cried all the way through drawing this spread. It is truly the one scene in the book that I hope people will spend time on. All the images are based on real people and real situations. There is a scene depicting a woman in a hospital room with nurses coming in with a birthday cupcake for her, which is based on the real story of a woman who turned 82, I think, on her third day in the ICU. She died the next day, and the nurses were her stand-in for family. There is an image of doctors and nurses who are exhausted and suiting up like they’re entering a war, an image of a nurse staring with dismay at a ventilator that she hopes will work and an image of a man holding up a sign outside the hospital, projecting his love and gratitude to the nurses and doctors who saved his wife’s life. I don’t remember how I chose the images. I just remember that there were too many to share.

“I didn’t have to paint evidence of love, I simply had to record it. That’s the best way I can explain it.”

I noticed that you’ve chosen to write the book in the past tense. Can you talk about that choice?

You know, no one has asked me that question before, and I had to think about it. Which means, of course, that the idea to write in past tense was a foregone conclusion at the time the book was made. I don’t think anyone on my publishing team even questioned that the book could be written any other way. What does that say about all of our mindsets at the time?

I truly believed that by the time of the book’s publication, this would all be past us. Remember, the book was made over a six-week period of time in June and July. I remember my editor stressing its value beyond this time frame—that we had to find lessons that were timeless, stories that went beyond the current situation, to make it worthy of being a book. I was always writing it from the perspective of the future, struggling to make sense of this time. The wild part is that we were making sense of it while we were going through it. Trying to wrap my head around that is like listening to Mrs. Who explain to Meg what a tesseract is in A Wrinkle in Time.

We’re still in the middle of this, but eventually our world will catch up to the past tense of the book.

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our review of Outside, Inside.

Can you talk about some of the ways you used color in these illustrations?

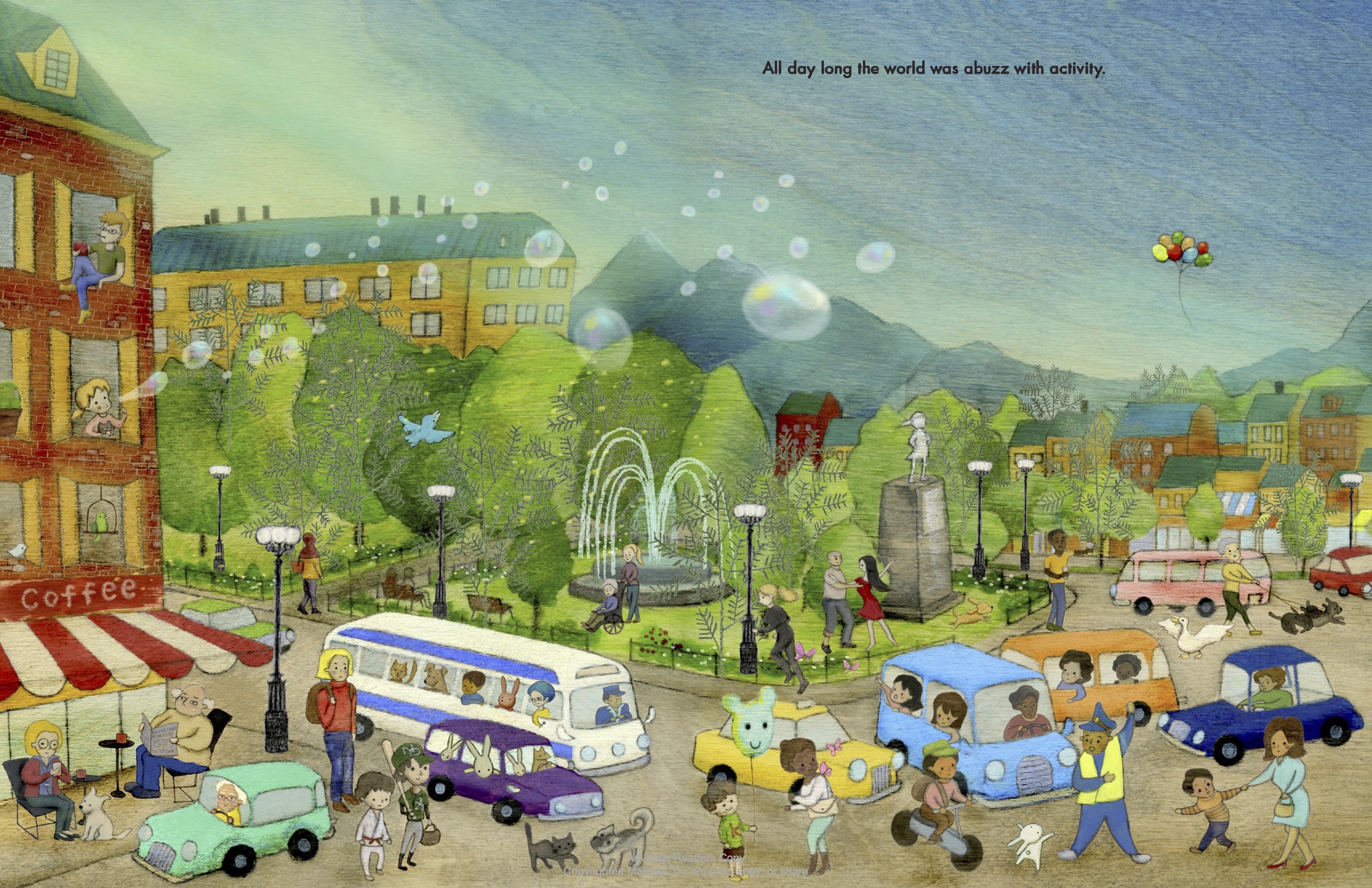

I used color to communicate ideas that simply couldn’t be put into words. I think the first two spreads are the best representation of this. The opening spread reveals a busy and colorful crowded street scene, with bright saturated colors and lots of reds and yellows. The next spread shows the world shut down, and the imposing grays and lack of colors illustrate that. From that point on, the book is painted in muted colors and grays. I wanted that to be felt immediately, that shift in color as we shifted to this new reality. The book gradually moves back toward color, as the world grows and signs of spring emerge.

A spread toward the end of the book talks about why we went inside and shows groups of people standing together. Some are in full color, and some are painted in a muted light blue. This is a spread of real people I found articles about at the time. The people who are painted in full color survived the virus. The figures painted in blue did not. The heartbreaking ones are the people in full color who stand in the arms of the people in blue.

And of course, the last spread of the book, the gatefold, opens to full color at last, as spring has finally returned. That’s an image that hasn’t yet come to pass as this book comes out into the world. It’s still a hope, as it was when I painted it this past year.

I love the character of the black cat who is featured in every illustration, including the cover, the endpapers and the title page. Do you have a cat? Was this cat part of the book from its inception? Can you talk about the role that the cat plays in the book?

I do have a cat. Her name is Sardine, and she’s a lovely striped tabby, not the sleek elegant cat of this book. I considered using Sardine as a model, but her colors are rather muted and would have made her hard to find in the grey images. I needed a little slip of a shadow, a figure who could weave in and out of the images without calling too much attention to itself but could be clearly seen.

The cat was always meant to be part of this book. She wasn’t in any of my original sketches, but I think her presence was felt even early on, before I’d turned it into a book. I knew I needed to have a narrator of sorts, a figure that children could enter the book with, a figure that couldn’t be human and could be relatable. At first I thought the animal should be a dog or a bird. But then I realized that of all the pets we have, the cat is the one animal that is allowed to have free rein both inside and outside. She was the perfect animal to follow.

I wanted her in the story because I needed there to be a stable presence on each page, someone that kids could follow through the scenarios with, could look for in some of the heavier images, a reliable force on the page. There’s something, even for adults, that is very reassuring about seeing this little creature on each page. It is, after all, a children’s book. It’s meant to comfort, to guide, to make you smile. That’s the job of this little cat.

“During these dark moments, I also saw evidence of more humanity than I ever suggested in my books.”

I want to ask about one more statement from your author’s note. You write, “My career has been devoted to drawing the world as I would like it to be, my version of a happy world. This is the first time that I have catalogued the world as it is.” How would you describe what it looks like and how it feels when you draw “the world as [you] would like it to be” versus “the world as it is”?

I’ve always drawn the world as though it exists without prejudice. Every book I’ve ever made, from my earliest picture books to my latest graphic novels, feature diversity and acceptance.

When I was growing up, I didn’t see myself in books very often. Being a person of color, and of mixed race at that, it was hard to identify with most picture and chapter books. I made it a goal for myself early on to reflect as much of the world’s population as I could within the 32 pages of a standard picture book. I chose stories that reflected people and characters caring for one another, which I wanted to see reflected more often in our society. I like to think I create a utopian world where everyone is accepted. When I illustrated God’s Dream by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, he often commented that he had selected me as his illustrator because he loved to see the love in my characters for one another. I guess you’d call it my own little artistic bubble—paint the world as you want it to be, and it will become that way.

It’s fair to say that the real world isn’t always this way. Outside, Inside was the first time I really allowed myself to paint exactly what I saw. The world is filled with injustice and disinformation and much more anger than I’d ever allowed myself to believe. But during these dark moments, I also saw evidence of more humanity than I ever suggested in my books. The human spirit, when put to the test, can be quite amazing. I didn’t have to suggest a utopian society this time, because there were elements of selflessness and graciousness and simple kindness that I witnessed every day. It’s a reminder that perhaps the fantasy we tell ourselves and the reality we choose to live can be one and the same. I didn’t have to paint evidence of love, I simply had to record it. That’s the best way I can explain it.

The book’s back cover is an illustration of a kitchen scene, with a loaf of what looks to be sourdough bread on the table. Did you get into baking your own bread during quarantine? Did you pick up any other new hobbies or ways of spending time?

Who didn’t get into baking during this time? It’s the one thing the rational side of my brain could latch onto and feel like it was accomplishing something. Yes, I make bread now. I haven’t gone so far yet as to make a starter. From what I hear, they’re almost like pets, because you need to devote so much time to feeding them every day. But it’s been nice discovering how pliable my kitchen is.

We also take lots more walks together as a family, just around our neighborhood. I’ve gotten more creative with cooking. We’ve introduced the kids to “The Twilight Zone”; we don’t have our television hooked up to regular broadcasting, so they’ve never really watched TV shows before. I’ve learned to cut hair. But for the most part, I’m sticking to making books.

Photo of LeUyen Pham by Anouk Kluyskens. Illustration from Outside, Inside used with permission of Macmillan Children's Publishing Group.

Each of these things together can make a book, but if you’re falling down on any part of those responsibilities, chances are the book won’t find its legs. Being an editor, then, is about making every part of the process personal—and that's even more the case if you’re running your own imprint. The stakes are high because my name is on it, sure, but also because I desperately want success for the authors and illustrators and the books they’re birthing.

Each of these things together can make a book, but if you’re falling down on any part of those responsibilities, chances are the book won’t find its legs. Being an editor, then, is about making every part of the process personal—and that's even more the case if you’re running your own imprint. The stakes are high because my name is on it, sure, but also because I desperately want success for the authors and illustrators and the books they’re birthing. I read that you were introduced to illustrator

I read that you were introduced to illustrator  Illustrators, I find, believe it or not, trolling Instagram. There are so many beautiful artists showing off their work there—proving they can tell a story through pictures. I have a folder and I save posts that catch my eye. I can get lost for hours reveling in the art and plotting who would be the perfect pairing for the stories that come my way, especially if they’ve never illustrated books.

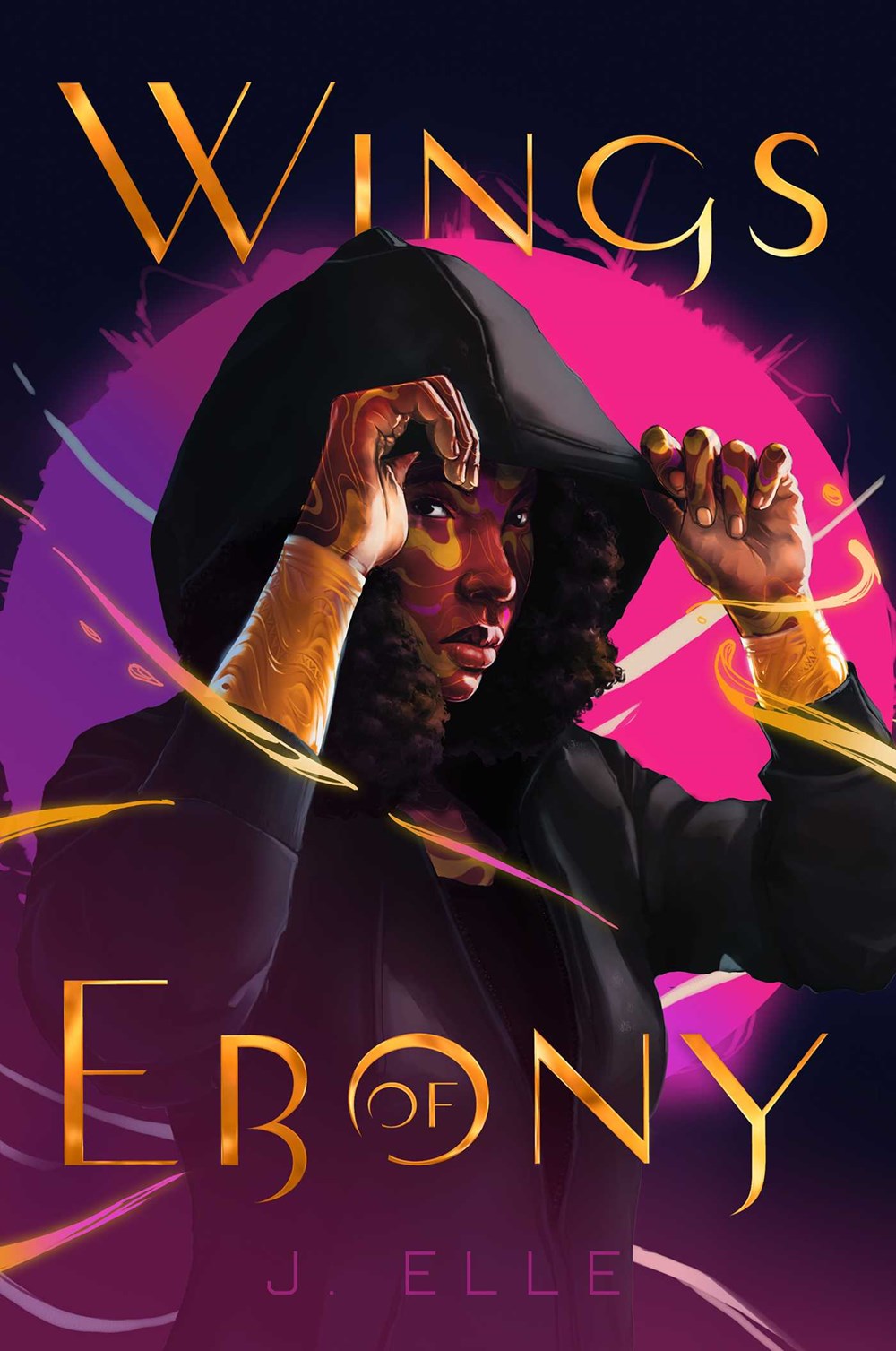

Illustrators, I find, believe it or not, trolling Instagram. There are so many beautiful artists showing off their work there—proving they can tell a story through pictures. I have a folder and I save posts that catch my eye. I can get lost for hours reveling in the art and plotting who would be the perfect pairing for the stories that come my way, especially if they’ve never illustrated books. And then my first YA novel debuts early next year—J. Elle’s fantasy novel, Wings of Ebony. It’s a magical story about a Black girl who discovers she is half-god, half-human, with magical powers she uses to liberate her beleaguered inner city Houston, Texas, community from the hands of racists who are flooding it with crime and drugs. It’s a thrill ride—think Black Panther meets Wonder Woman—and the first book in a series. I’m super excited for that book and for J. Elle, who is a dynamic debut author.

And then my first YA novel debuts early next year—J. Elle’s fantasy novel, Wings of Ebony. It’s a magical story about a Black girl who discovers she is half-god, half-human, with magical powers she uses to liberate her beleaguered inner city Houston, Texas, community from the hands of racists who are flooding it with crime and drugs. It’s a thrill ride—think Black Panther meets Wonder Woman—and the first book in a series. I’m super excited for that book and for J. Elle, who is a dynamic debut author.

When I look at the book now, there’s a rhythmic pattern in its fluctuation between sorrow and connection. I'm chalking that up to my brain going into automatic children’s book mode, my editor’s gentle guidance, my agent’s encouragement and some universal wave we were all riding. We were all looking for that balance. Drawing it into pictures just clarified it all.

When I look at the book now, there’s a rhythmic pattern in its fluctuation between sorrow and connection. I'm chalking that up to my brain going into automatic children’s book mode, my editor’s gentle guidance, my agent’s encouragement and some universal wave we were all riding. We were all looking for that balance. Drawing it into pictures just clarified it all.

Barb Rosenstock: It wasn’t me. I don’t think to ask those “who did what” questions because picture books are the ultimate team sport. We all work with and around each other’s ideas and opinions for four years, and then we wind up with a book—so I don’t know, but it is perfect.

Barb Rosenstock: It wasn’t me. I don’t think to ask those “who did what” questions because picture books are the ultimate team sport. We all work with and around each other’s ideas and opinions for four years, and then we wind up with a book—so I don’t know, but it is perfect. Mary GrandPré: It was my idea. I like to design the title type while I am in the concept stage of the cover art, and the Monet signature seemed like a good way to bring that feeling of brushstrokes into the cover.

Mary GrandPré: It was my idea. I like to design the title type while I am in the concept stage of the cover art, and the Monet signature seemed like a good way to bring that feeling of brushstrokes into the cover.