Jaime Cortez is a celebrated Chicano graphic novelist, visual artist, writer, teacher, performer and LGBTQ rights activist. His collection of short stories, Gordo, reveals that he also possesses the eye of a photographer. Like Diane Arbus or Weegee, Cortez depicts warts-and-all moments of vulnerability precisely, sometimes even harshly, and without sentiment. Unlike Arbus and Weegee, his camera is the printed word, rather than a Nikon or Speed Graphic.

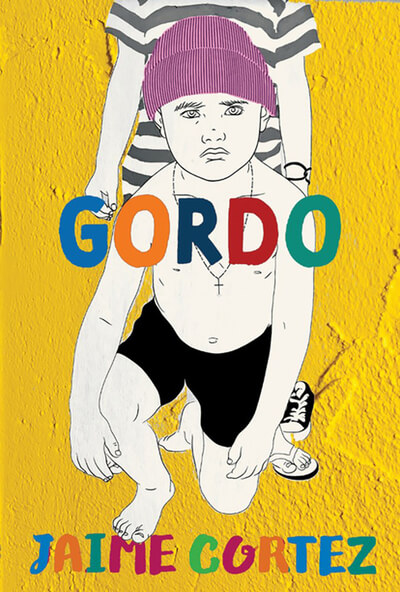

The protagonist of many of these short stories is a young lad nicknamed Gordo who feels confused by the world as he grows into his oversize frame during the 1970s. He lives in the ag-industrial maw of central California, where a person’s horizons are frequently circumscribed by the limited choices available (working in the fields or trundling off to one of the mega food processors that stipple the landscape), particularly if that person’s first (or only) language is Spanish.

Like many of John Steinbeck’s characters in The Grapes of Wrath and Cannery Row, the people who inhabit the pages of Gordo are often poor in economic terms but lead richly complex lives. There’s Raymundo, who as a boy is bullied for growing his hair long, and as an adult unexpectedly finds himself in a position to assist a former classmate. Nelson Pardo is an Salvadoran ex-army colonel who hates his janitorial gig at the Jolly Giant vegetable plant. And an accident with a chainsaw reveals Alex’s gender to Gordo, who is shocked by the realization that everybody else already knew.

Cortez is native to this locale, and it shows. He succinctly portrays a largely overlooked California landscape that’s as far removed from the worlds of Silicon Valley and Hollywood as it is from the 14 moons of Neptune. What ultimately draws the reader in, though, is the book’s emotional honesty. Gordo is no smarty-pants, wise-beyond-his-years kid; even as he grows up, he’s often puzzled by life’s abundant mysteries. The characters in and around his life exhibit kindness and cruelty in fluid motion. Cortez artfully frames these characters’ daily struggles and captures them in the freeze-frame flash of a master at work.

Note: Edited for clarity on 9/20/2021.