Tips for Teachers is a monthly column in which experienced teacher and children’s librarian Emmie Stuart shares book recommendations and a corresponding teaching guide for fellow elementary school teachers.

I’ve been meeting with my students virtually for about eight weeks. Last week, I asked them to share what they miss most about school. Most of them answered without hesitation: They miss their friends.

Childhood friendships are some of the most formative, intense and enriching friendships we’ll ever have. My best friend from kindergarten came to town this weekend. Spending time with her renewed my weary spirit and reminded me that there is life beyond face masks and virtual happy hours. As Alexander McCall Smith writes in The Ladies’ No. 1 Detective Agency, “You can go through life and make new friends every year—every month practically—but there was never any substitute for those friendships of childhood.”

The following two books demonstrate the tenderness and joy of childhood friendships.

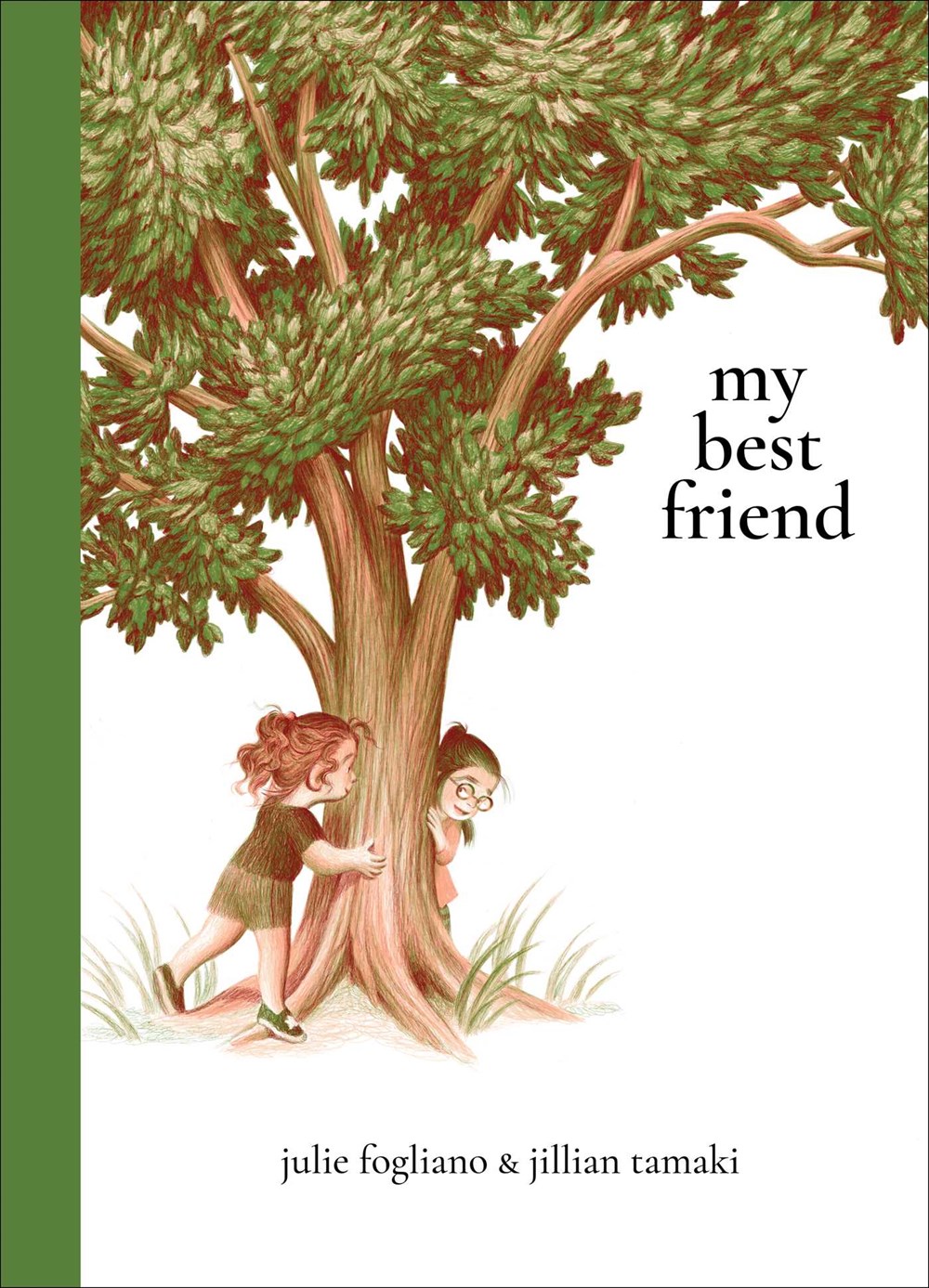

My Best Friend

My Best Friend

By Julie Fogliano, illustrated by Jillian Tamaki

A little girl meets a new friend at a park. Her new friend “laughs at everything” and is “so smart.” The two girls learn more about each other as they twirl, create, pretend and explore the park together. Their adventures and commonalities lead the narrator to the conclusion that “she is my best friend / i think.” Only at the story’s end does author Julie Fogliano reveal that the girls have yet to know each other’s names.

Making predictions before reading

Students who are asked to make predictions before they read will form connections between their own personal knowledge and what they discover in a book. This is a great strategy for keeping readers actively engaged.

Before reading, hold up the cover of My Best Friend and ask, “What do you predict will happen to the two girls you see here? Why do you think the illustrator used only two shades of colors? Do you have a best friend? What makes a best friend? How do we make new friends?”

The whole book approach

Educator and children’s literature scholar Megan Dowd Lambert created the whole book approach as a way to invite children to engage with all the parts of a picture book—not just the story but also the illustrations and production and design elements—in order to support both visual and verbal literacy. My Best Friend provides ample opportunities to try this approach with young readers. Here are some elements you can discuss.

Typography

Text placement throughout the book varies; there are only a few capital letters (the words “LOVES” and “HATES” are written in all caps), and the only punctuation is a period after the book’s final phrase. Show students the page with “skeleton hand” leaves; the word “Boo” is capitalized and set in a larger size that spans across the page. Ask, “How does the size and shape of this word show us how to read it?” A few cursive letters illustrate the narrator’s “fanciest” handwriting. Ask students whether they think these letters are part of the book’s text or its illustrations.

Color

My Best Friend employs a limited color palette dominated by warm, rosy peaches and deep forest greens. Ask students why they think illustrator Jillian Tamaki chose these colors.

Lines and white space

The illustrations’ ample white space and the book’s white background keep visual focus on the book’s vignettes and full-spread images. Several of the vignettes run off the edge of the page. The illustrations contain many fine lines that add texture and movement, and the girls’ adventures are dominated by curves and swirling lines. Prompt students to speculate about what kinds of artistic materials illustrator Jillian Tamaki used to create the images. What is the effect of her choice to “cut off” some of the images on the edge of the page?

Production elements

Underneath the dust jacket, the book’s case cover features a wraparound illustration of the girls playing hide-and-seek. Ask students to reflect on this image before and after reading the book. The book’s front and back endpapers are a warm chestnut shade of brown, while its back jacket is forest green. Ask students to speculate about why these two colors were chosen. The book has a strong portrait orientation. Discuss why this shape was the best choice for the book.

Cross-curricular activities

With a little creative thinking, it’s easy to create activities that incorporate picture books into many parts of the curriculum. Here are a few ideas for activities to extend learning after reading My Best Friend.

Personal reflection

Discuss what activities students like to do with friends. What is something about ourselves that our good friends understand? Invite younger students to respond to these prompts and the discussion through drawings or other visual art. Invite older students to respond through journaling.

Nature art

The two girls in My Best Friend make skeleton hands out of leaves. Take students outside and give them time to create something from items they find. Divide them into small groups to share their creations.

Similarities and opposites

The narrator of My Best Friend hates strawberry ice cream, but her new best friend loves it. Divide students into pairs and let them interview each other. Each pair must determine one way in which they are alike and one way in which they are different. Gather students back together and prompt them to share what they learned about one another.

Creative movement

The narrator makes her new friend laugh by pretending to be a pickle. Divide students into pairs. Ask one partner to name a noun; their partner must act out the word.

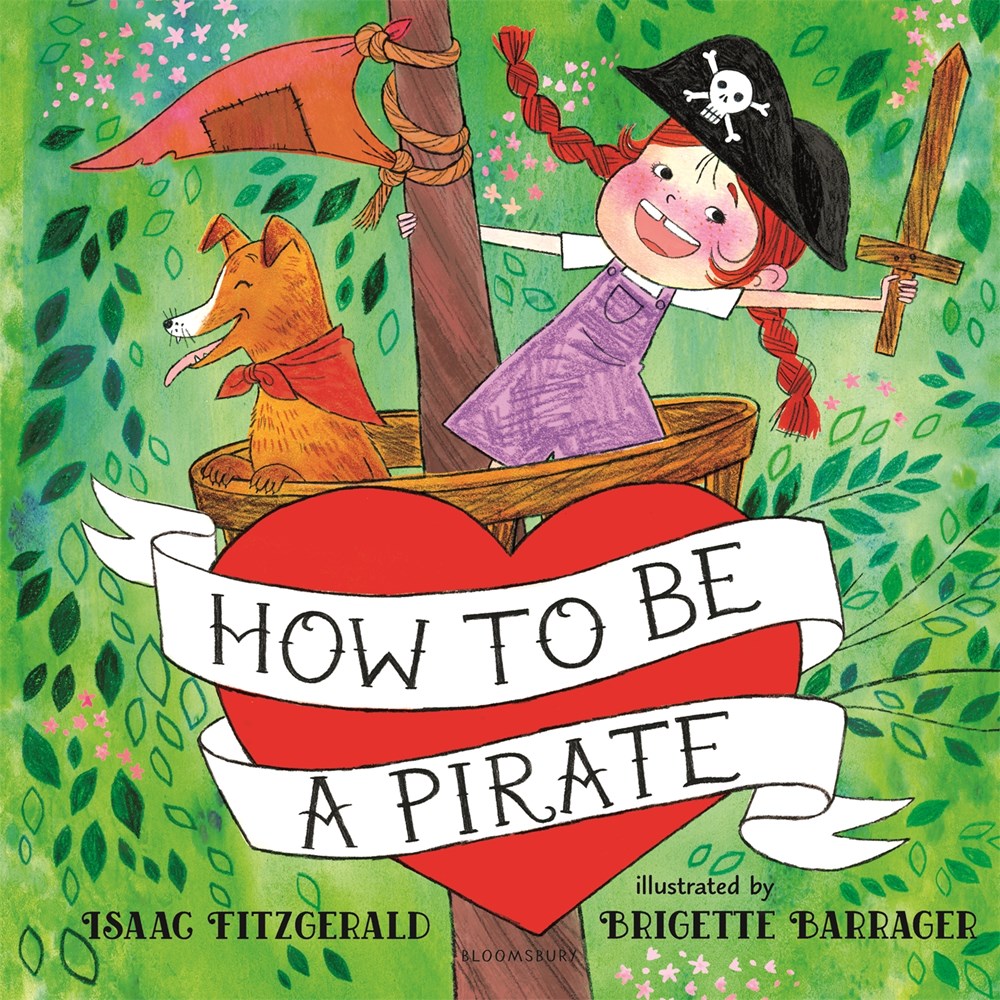

How to Be a Pirate

How to Be a Pirate

By Isaac Fitzgerald, illustrated by Brigette Barrager

When her aspirations are squashed by neighborhood boys who tell her she can’t be a pirate, CeCe visits her grandfather. She asks him, “What’s it like to be a pirate?” Using his tattoos as inspiration, Grandpa tells CeCe that pirates are brave, quick, fun and independent—but the most important thing a pirate needs is love. Her spirit renewed, CeCe returns to the boys with an emboldened and tenacious spirit. How to Be a Pirate wonderfully explores themes of intergenerational friendship, self-confidence and imaginative play.

Dialogic read aloud

Read How to Be a Pirate once straight through without stopping. Then read it again and pause to ask the following questions and to discuss students’ responses.

- How do you think CeCe feels on the title page of the book? What makes you say that?

- Before CeCe goes inside Grandpa’s house, what do the illustrations tell us about Grandpa?

- Once the illustrations show us Grandpa’s living room, what clues can you find to tell you even more about him?

- Why does CeCe believe that Grandpa can teach her how to be a pirate?

- Are CeCe and Grandpa really on a ship or in a jungle? What evidence can you find in the illustrations?

- Do you notice anything about the dog?

- Grandpa says pirates must be independent. Do you agree? Why or why not?

- How does Grandpa show CeCe that he loves her?

- What other traits can you think of that would help CeCe face the boys and be a pirate?

Writing letters

Ask students to think about different types of friends. For many students, conceptualizing a grandparent, a beloved pet or a cousin as a “friend” will be a novel idea, so ask students to think about a friend who is not in their classroom or in their grade level. Give them time to make a list of the ways this friend enriches their life, then guide students in transforming their lists into letters to their friends. Be sure to provide logistical instructions on how to fold, address and mail the letter.

Future homes

Readers learn so much about Grandpa through Brigette Barrager’s illustrations of his home. Ask students about their goals for when they are older. Provide pieces of oversized drawing paper and drawing supplies and challenge them to draw a house that reflects their future aspirations. For example, a librarian’s house might have lots of bookshelves and a Little Free Library in the front yard. An artist’s or musician’s home might have a studio. Encourage them to add details to their houses’ interiors and exteriors.

Gender stereotypes

Children receive messages about gender norms from birth. Invite students to categorize imaginative play activities as “for girls” or “for boys.” Let their responses guide you toward questions that give them space to consider why they consider activities to be divided between these categories. Provide time for them to share moments when they were excluded from playing with others or stereotyped because of their gender.