Thank goodness Jennifer Doudna didn’t listen to her high school guidance counselor, who told her that girls don’t do science. Instead, Doudna followed her passion and pursued biochemistry, inspired by her childhood explorations of beaches, meadows and lava flow caves in her hometown of Hilo, Hawaii. When Doudna read James Watson’s book The Double Helix as a sixth grader, she realized that “science can be very exciting, like being on a trail of a cool mystery and you’re getting a clue here and a clue there. And then you put the pieces together.”

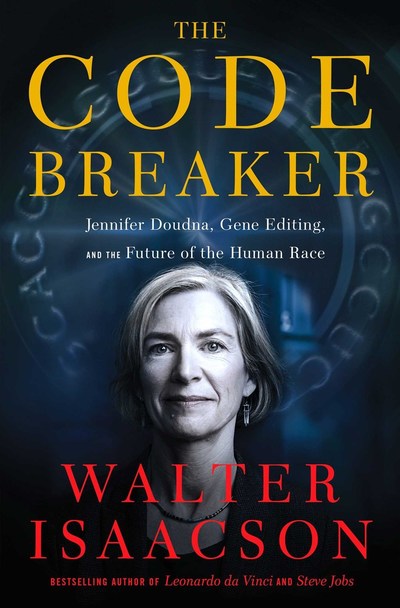

That’s exactly the feeling you’ll have while reading Walter Isaacson’s marvelous biography The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race. It’s a hefty but inspiring book that chronicles Doudna’s and others’ development of the gene-editing tool CRISPR. With his dynamic and formidable style, Isaacson explains the long scientific journey that led to this tool’s discovery and the exciting developments that have followed, noting, “In the history of science, there are few real eureka moments, but this came pretty close.”

Like Lab Girl on steroids, The Code Breaker paints a detailed picture of how scientists work. As Doudna interacts with a variety of talented colleagues over the years (color photos are included), she experiences excitement, uncertainty, rivalry, betrayal and more. At one moment she’s joyfully stirring spaghetti while explaining CRISPR to her 9-year-old son; during another, she’s standing in her backyard in the middle of a rainy night, reeling from the realization that leaving her academic post at the University of California, Berkeley to work in the genetics industry was a huge mistake.

The timing of Isaacson’s book could hardly be better. He was well into his research and writing when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and while many of us were baking bread and worrying about toilet paper, Doudna headed to Berkeley to lead one of the teams developing diagnostic tests and messenger RNA (or mRNA) vaccines, catapulting CRISPR into the global spotlight as a lifesaving tool. The Code Breaker includes a lengthy section about these recent events, culminating in Doudna winning a Nobel Prize in October 2020. As the Moderna chairperson put it when he saw the promising clinical trial results of the company’s vaccine, “It was a bad day for viruses. . . . We may never have a pandemic again.”

In addition to being an accomplished historian of science and technology, Isaacson is a professor at Tulane University and former editor of Time magazine. His previous biography subjects include Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs—all united by their creative intellect and natural curiosity. As a biographer, Isaacson is truly an immersive tour guide, combining the energy of a TED Talk with the intimacy of a series of fireside chats. For this book, he tried his hand at gene editing and enrolled in Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. He takes a big-picture approach to CRISPR’s significance and legacy as well, discussing its many uses for treating diseases such as sickle cell anemia, while also considering the myriad complicated moral issues surrounding CRISPR’s use.

For readers seeking to understand the many twists, turns and nuances of the biotechnology revolution, there’s no better place to turn than The Code Breaker.