America may have abolished Jim Crow laws, but prejudice is a clever shape-shifter. Certainly, the black experience is not solely defined by injustices inflicted by white America. Regardless, the black experience in this country cannot be discussed without the ever-looming menace of racism and the complementary institution of white supremacy. These four recent releases offer a nuanced spectrum of views on what it means to be black in America.

For many Americans who believed in the concept of “colorblindness,” the election of Donald Trump abruptly shattered the myth of a post-racial America. Yet for many minorities, the unapologetic racism and bigotry that helped elect Trump served as a reminder that the institution of white supremacy is alive and thriving. At a young age, Patrisse Khan-Cullors learned that blackness functioned as a target and watched as racism chipped away at the humanity of her loved ones. Yet Khan-Cullors, who co-founded the Black Lives Matter movement with Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, found strength within the unconditional love she held for her family, which provided a refuge from the dehumanization tactics of white supremacy. The title of her memoir, When They Call You a Terrorist, co-authored with asha bandele, references the labeling of Black Lives Matter as a terrorist movement by conservative media outlets, politicians and government officials. According to a report leaked by Foreign Policy, the FBI’s counterterrorism division determined that “black identity extremists” were a violent group of domestic terrorists. Activists such as Khan-Cullors cite this assessment as an example of dog-whistle politics. For those under the banner of white supremacy, it’s deemed radical to say that black lives matter—because black people are rarely seen as human.

HARD TO SAY

Talking about race in America can feel like chatting with a mouth full of thorns. Even for the white Americans who vow to be allies, talking about race is taboo: If you’re not racist, then why are you noticing skin color in the first place? Equal parts an excavation of personal history and a piece of sharp political commentary, author Ijeoma Oluo inhabits a narrative tone that is neither condescending nor coddling in So You Want to Talk About Race. Racism in America can take the form of so much more than the “N” word, and here Oluo astutely dismantles issues such as police brutality, cultural appropriation and microaggressions, and the pervasive, poisonous power of racism and white supremacy. Balancing the intimacy of a memoirist with the dedication of an investigative journalist, Oluo recognizes that her offerings are a starting point. The work required to effectively battle racism can begin with conversation, but if these principles are not put into consistent practice, then lasting change has little chance. Systemic racism benefits from silence just as much as it thrives under white liberals who refuse to check their privilege—those who assume that proximity to their black friend, love interest or neighbor proves that they are not complicit. So You Want to Talk About Race argues that with the right tools, discussions about race in America can serve as bridges rather than battlefields.

FINAL WORDS

In 2014, the killing of 43-year-old Eric Garner, a black Staten Island resident and neighborhood fixture, was caught on video. The footage shows white New York City police officer Daniel Pantaleo wrestling Garner to the ground and using what appears to be an illegal chokehold. Garner struggles, uttering those infamous last words, “I can’t breathe.” The medical examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide. Regardless, a grand jury chose not to indict Pantaleo on a charge of murder. In I Can’t Breathe: A Killing on Bay Street, a carefully constructed and researched portrait of Garner, Rolling Stone staff writer and author Matt Taibbi utilizes the tragedy to hold a mirror to the degrading, demoralizing and crippling manifestations of American racism. I Can’t Breathe not only examines the wide-reaching effects of racism but also specifically breaks down how the ideas of “law and order” contribute to a system of racist, predatory policing. Although Taibbi recognizes that Garner had his flaws, he pushes beyond them to compile a rich, nuanced depiction of a devoted family man who became yet another victim of bad luck, unforgiving environmental circumstances and the racially fueled injustices of the country’s police forces. I Can’t Breathe demands readers ask: Who are the police really intended to protect?

AMERICAN GLORY

When we think of the black renaissance, we typically conjure images of bustling Harlem streets and flashy zoot suits alongside the black excellence of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. We may even think of Chicago and its cultural icons such as author Richard Wright and playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Memoirist and reporter Mark Whitaker’s Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance is a thoroughly researched celebration of the black community and culture in Pittsburgh from the 1920s through the 1950s. Pittsburgh’s black residents, Whitaker argues, offered cultural contributions that significantly shaped black history—and the nation. With the diligence of a seasoned anthropologist, Whitaker spotlights the city’s stunning feats of black achievement and resilience through the lens of his extensive cast of influencers and icons. While some of the names may be unfamiliar, each subject’s narrative is a nuanced portrayal meant to challenge our country’s often narrow, dismissive version of black history. Cultural heavyweights such as boxer Joe Louis are treated as historical catalysts rather than extraordinary oddities. Black history, as evident in the cultural renaissance of Pittsburgh, is not defined by oppression. Despite the setbacks of systemic racism and discrimination, black excellence flourishes regardless of the white gaze.

This article was originally published in the February 2018 issue of BookPage. Download the entire issue for the Kindle or Nook.

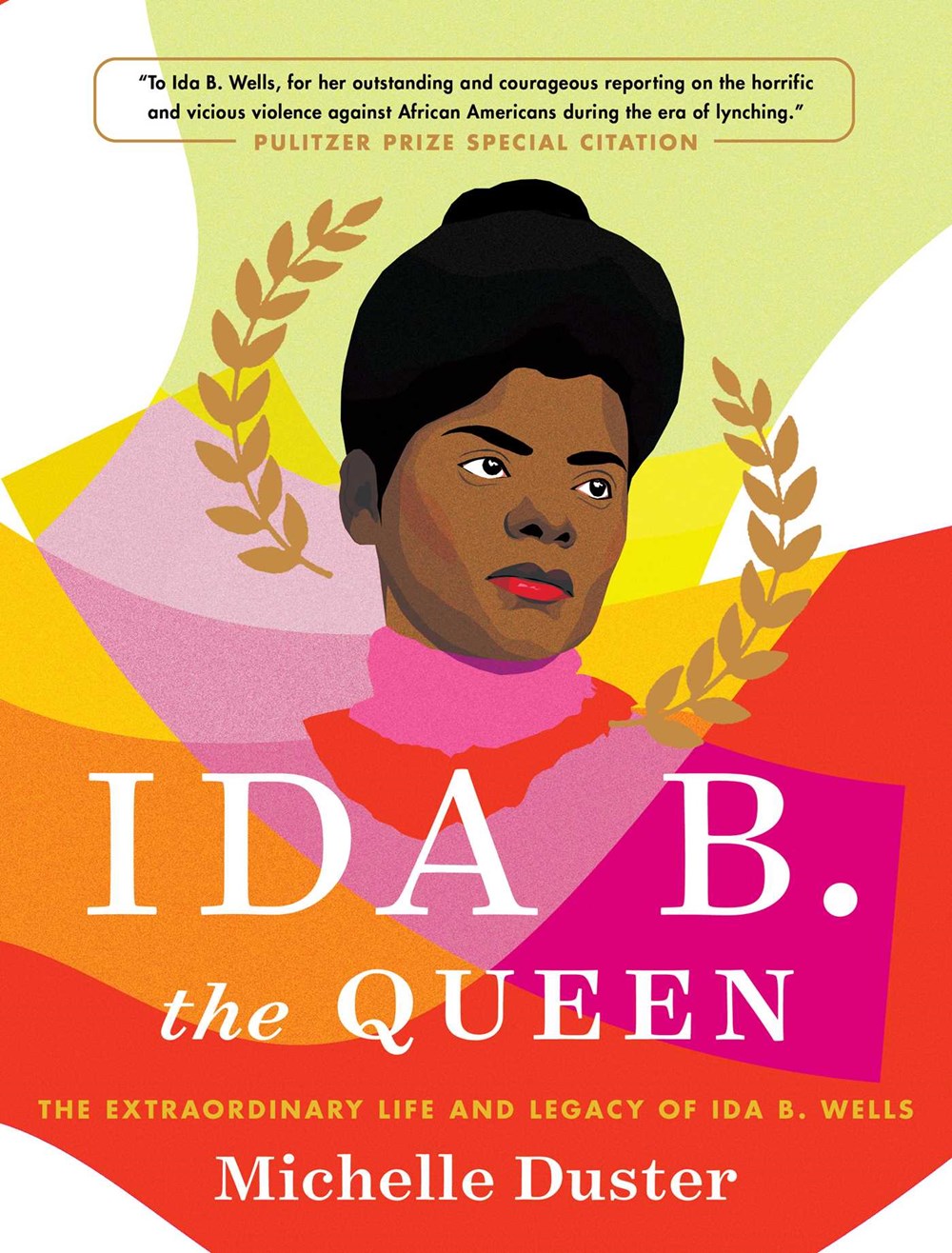

Ida B. Wells gets the royal treatment in Ida B. the Queen: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells, written by Michelle Duster, Wells’ great-granddaughter.

Ida B. Wells gets the royal treatment in Ida B. the Queen: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells, written by Michelle Duster, Wells’ great-granddaughter. If you’re looking for a single work that spans the entirety of the Black experience in America, pick up a copy of Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619–2019, edited by

If you’re looking for a single work that spans the entirety of the Black experience in America, pick up a copy of Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619–2019, edited by  One valuable yet often overlooked leader in the fight for Black equality is finally getting his due in Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement. The late author’s lectures from his prolific teaching career, assembled here for the first time, are full of firsthand lessons from his direct involvement in the civil rights movement.

One valuable yet often overlooked leader in the fight for Black equality is finally getting his due in Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement. The late author’s lectures from his prolific teaching career, assembled here for the first time, are full of firsthand lessons from his direct involvement in the civil rights movement. Imagine being woken up in the middle of the night by a mob outside your house, calling your name, accusing you of crimes that you didn’t commit. Then imagine that they start throwing explosives and firing guns at your house, at your family. You defend yourself and your home as best you can, and one of the assailants dies from the intervening fight. Suddenly you find yourself, a Black man, a formerly enslaved person, fleeing through 1890s Kentucky, trying to stay out of the hands of lynch mobs. With the Ku Klux Klan and newspapers calling for your execution, you’re forced to put your life in the hands of a lawyer who fought to uphold slavery.

Imagine being woken up in the middle of the night by a mob outside your house, calling your name, accusing you of crimes that you didn’t commit. Then imagine that they start throwing explosives and firing guns at your house, at your family. You defend yourself and your home as best you can, and one of the assailants dies from the intervening fight. Suddenly you find yourself, a Black man, a formerly enslaved person, fleeing through 1890s Kentucky, trying to stay out of the hands of lynch mobs. With the Ku Klux Klan and newspapers calling for your execution, you’re forced to put your life in the hands of a lawyer who fought to uphold slavery. If you’re looking for something lower octane that still offers an intriguing exploration of what could have been, take a trip to Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia. Author

If you’re looking for something lower octane that still offers an intriguing exploration of what could have been, take a trip to Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia. Author  For education that’s easy on the eyes, snag The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker (

For education that’s easy on the eyes, snag The Black Panther Party: A Graphic Novel History by David F. Walker (