Breathtaking picture books, heartwarming chapter books and enthralling middle grade books await young readers—or anyone who enjoys a good story—in our list of most anticipated children’s books this fall.

Sam’s Super Seats by Keah Brown, illustrated by Sharee Miller

Kokila | August 23

Author Keah Brown created the viral hashtag #DisabledAndCute to challenge widespread misperceptions and representations of disabled people, themes she also explored in The Pretty One, her essay collection for adult readers. In Sam’s Super Seats, her first picture book, Brown introduces Sam, a girl who has cerebral palsy, which means that sometimes she needs to sit down and rest. Engaging illustrations by Sharee Miller capture a fun shopping trip to the mall that Sam shares with her friends before the first day of school. Cheerful and conversational, Sam’s Super Seats is an intersectional addition to the back-to-school picture book canon.

Patchwork by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Corinna Luyken

Putnam | August 30

In recent decades, the Newbery Medal has typically honored longer works of children’s literature, so author Matt de la Peña defied both convention and expectation by winning the 2016 Newbery for Last Stop on Market Street, a picture book that also earned illustrator Christian Robinson a Caldecott Honor. De la Peña has been on a hot streak ever since, publishing two more books with Robinson (Carmela Full of Wishes and Milo Imagines the World) as well as Love, which features art by Loren Long.

In the meantime, illustrator Corinna Luyken has established a name for herself via thoughtful picture books, including the bestsellers My Heart and The Book of Mistakes, her 2017 debut, as well as through her work with writers such as Kate Hoefler (Nothing in Common) and Marcy Campbell (Something Good). Luyken and de la Peña’s first picture book together, Patchwork is a poetic ode to possibility that’s perfect for readers who love de la Peña’s lyricism and Luyken’s effortlessly impressionistic art.

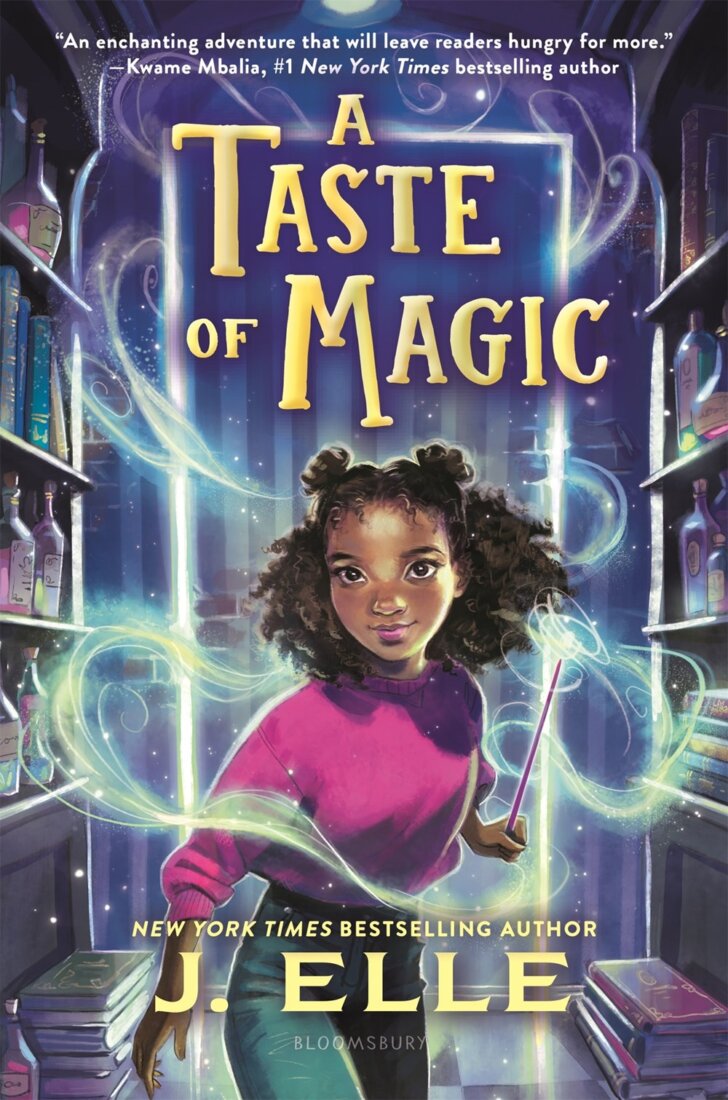

A Taste of Magic by J. Elle

Bloomsbury | August 30

We don’t like to pat ourselves on the back too much, but we did highlight author J. Elle’s debut novel, a YA fantasy called Wings of Ebony, as one of our most anticipated books of 2021, and the book went on to become an instant bestseller and establish Elle as one of the most exciting new voices in YA. So we were thrilled when Elle’s first book for younger readers, A Taste of Magic, was announced. The story of a young witch named Kyana who enters a baking contest in the hopes of using the prize money to save her magical school, A Taste of Magic looks enchantingly scrumptious.

Magnolia Flower by Zora Neale Hurston, adapted by Ibram X. Kendi, illustrated by Loveis Wise

HarperCollins | September 6

Earlier this year, HarperCollins announced an ambitious new project: National Book Award-winning author and scholar Ibram X. Kendi would adapt six works by Zora Neale Hurston for young readers. Hurston is best known today as a novelist, but she also wrote short stories and collected folk tales as an anthropologist throughout the South. In this first volume, Kendi’s adaptation of one such short story is paired with vibrant illustrations by Loveis Wise, a rising star who has recently illustrated picture books by Ibi Zoboi (The People Remember) and Jeanne Walker Harvey (Ablaze With Color). We can’t think of two people more perfectly suited to bring Hurston’s work to a new generation of readers.

Spy School: Project X by Stuart Gibbs

Simon & Schuster | September 6

In the decade since middle grade author Stuart Gibbs published Spy School, a mystery novel about a boy named Ben who attends the CIA’s top secret Academy of Espionage, Gibbs has written nine more books in his Spy School series. What’s more, he’s also released books in four additional blockbuster series, publishing 14 titles across them. This year, Gibbs publishes his 10th Spy School novel, the opaquely titled Spy School: Project X, in which Ben will go head to head with his longtime nemesis. How is it possible, we ask, to create such consistently thrilling, entertaining reads at such a rapid pace while also getting the recommended eight hours of sleep every night? Our current working theory involves clones, but if Gibbs wants to enlighten us, he knows how to find us.

Farmhouse by Sophie Blackall

Little, Brown | September 13

In the 84-year history of the Caldecott Medal, only a handful of illustrators, including Barbara Cooney, David Wiesner, Leo and Diane Dillon and Robert McCloskey, have won multiple medals. Author-illustrator Sophie Blackall joined their rarified ranks in 2019 when she won her second medal for Hello Lighthouse. (She won her first in 2016 for Finding Winnie.) To create Farmhouse, Blackall incorporates mixed media into her illustrations as she tells a remarkably personal story about a family and their home.

Odder by Katherine Applegate, illustrated by Charles Santoso

Feiwel & Friends | September 20

Author Katherine Applegate has been turning kids into readers with fantastical stories filled with heart for more than two decades, and we’re fortunate that the 2013 Newbery Medalist shows no sign of slowing down. In order to know whether you’ll love this novel in verse about a young sea otter whose life is changed at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, you really only need to look at the cover. Seriously, we dare you to attempt to resist its charms.

The Door of No Return by Kwame Alexander

Little, Brown | September 27

Poet Kwame Alexander took the world of children’s literature by storm when he won the 2015 Newbery Medal for The Crossover, a novel in verse. Not content to rest on his laurels, Alexander won a Newbery Honor in 2020 for The Undefeated, a picture book for which illustrator Kadir Nelson also won the Caldecott Medal. The Door of No Return sees Alexander take another exciting, ambitious step forward, this time into historical fiction. The novel opens in West Africa in 1860 and follows a boy named Kofi who is swept up into the unstoppable current of history.

Meanwhile Back on Earth . . . by Oliver Jeffers

Philomel | October 4

Author-illustrator Oliver Jeffers is one of the most successful picture book creators working today. He’s sold more than 12 million copies of titles that include Stuck, The Heart and the Bottle and, of course, The Day the Crayons Quit, which features text by author Drew Daywalt paired with Jeffers’ unmistakable artwork. Meanwhile Back on Earth continues a theme Jeffers has been exploring since his 2017 book, Here We Are, portraying a parent introducing their children to some aspect of human existence. In this case, Jeffers addresses the long history of conflict among people.

A Rover’s Story by Jasmine Warga

Balzer + Bray | October 4

If you loved Wall-E and Peter Brown’s The Wild Robot, or if looking at the recently released photographs from the James Webb Space Telescope filled you with awe and wonder, you won’t want to miss Jasmine Warga’s middle grade novel A Rover’s Story. Warga has a knack for plumbing the emotional depths of a story, so imbuing a Mars rover with humanity and heart seems like exactly the sort of new challenge we love to see authors take on.

The Real Dada Mother Goose by Jon Scieszka, illustrated by Julia Rothman

Candlewick | October 11

Author Jon Scieszka began his kidlit career with three postmodern picture books: The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs!, illustrated by Lane Smith; The Frog Prince, Continued, illustrated by Steven Johnson; and The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, another collaboration with Smith that earned a Caldecott Honor. In the three decades since, Scieszka has brought his signature humor to chapter books, middle grade novels and a memoir. He even served as the first National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. He comes full circle with The Real Dada Mother Goose, partnering with illustrator Julia Rothman to offer a new take on another beloved work of children’s literature, Blanche Fisher Wright’s The Real Mother Goose. We can practically hear the storytime giggles now.

I Don’t Care by Julie Fogliano, illustrated by Molly Idle and Juana Martinez-Neal

Neal Porter | October 11

Picture books illustrated by multiple illustrators aren’t unheard of, though in such cases, each illustrator typically works individually, creating separate images and giving each page a different look and feel. It’s much less common for illustrators to truly collaborate and create artwork together, as Caldecott Medalists Molly Idle and Juana Martinez-Neal did with I Don’t Care, a quirky ode to friendship with text by bestselling author Julie Fogliano. We hope their work inspires more collaborative picture books in the future.

Our Friend Hedgehog: A Place to Call Home by Lauren Castillo

Knopf | October 18

Caldecott Honor recipient Lauren Castillo published Our Friend Hedgehog: The Story of Us in May 2020—little more than two years ago, and yet it feels like centuries have passed since then. Castillo completed our Meet the Author questionnaire in February of that year. “What message would you like to send to young readers?” we asked her. “Be brave,” she wrote, with no way of knowing how much bravery we were all about to need. In Our Friend Hedgehog: A Place to Call Home, Castillo returns at long last to the woodsy world of Hedgehog and her friends for more stories of adventure and friendship, and we can’t wait to join her there.

The Three Billy Goats Gruff by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen

Orchard | October 18

Author Mac Barnett and illustrator Jon Klassen first collaborated in 2012. The result of that collaboration, Extra Yarn, won a Caldecott Honor. They’ve since created five more picture books together, including Sam and Dave Dig a Hole, which won another Caldecott Honor, and the Shapes trilogy (Triangle, Square and Circle), all featuring Barnett’s dry wit and Klassen’s deceptively simple art. The duo will enter ambitious new territory this fall as they launch a planned series of reenvisioned fairy tales, beginning with the Norwegian story of The Three Billy Goats Gruff.

The Tryout by Christina Soontornvat, illustrated by Joanna Cacao

Graphix | November 1

In 2021, Christina Soontornvat joined an exclusive club, becoming one of only a few authors to receive Newbery recognition for two different books in the same year. What’s more, Soontornvat’s two Newbery Honors were for two very different books, a fantasy novel (A Wish in the Dark) and a work of narrative nonfiction (All Thirteen). But Soontornvat has always had range, publishing fiction and nonfiction picture books and a chapter book series in addition to her middle grade titles. With The Tryout, Soontornvat takes on two more new categories in one book: graphic novels and memoir. Accompanied by illustrations from webcomic artist Joanna Cacao, Soontornvat tells a story drawn from her own middle school experiences that fans of Jerry Craft’s New Kid and Shannon Hale’s Real Friends will enjoy.