I’m a real believer in the light bulb moment—not the Encyclopedia Brown version, in which all the clues fall neatly into place and the mystery is solved (ah-ha!), but the type of real-life experience in which a relatively small event creates a spark that inevitably becomes something grander and more exciting. When kids ask me “when did you know you wanted to be a cartoonist?” I tell them about my light bulb moment.

It happened when I was in second grade. Or maybe third. I’m not really a detail person. But I can very clearly recall being in the basement of our small house in New Hampshire with my older brother and some neighborhood friends. We were drawing with colored pencils. One of the boys—we called him Munch—announced that he was going to draw a picture of the Jolly Green Giant (we were all familiar with the TV commercials for Green Giant frozen vegetables), and he scooted off to a corner to work in private. After five minutes he’d finished it: a drawing of a green, leafy foot that filled up an entire 9×12 sheet of drawing paper. Slightly baffled, I asked, “Where’s the rest of him?” And Munch answered, “He was too big to fit on the page.”

Rimshot. Hello? Is this microphone on?

Okay, so 40 years later it’s not all that funny. But at the time, it was an absolute scream. All of us howled. And what I’ve since realized (although it escaped me at the moment, probably because I was laughing so hard) was that it was the first time I’d ever really seen someone create a cartoon. I was fascinated. Almost immediately I began reading all the comics I could get my hands on. Comic books were great, but they cost a quarter—or sometimes even 50 cents. I soon grew to prefer newspaper comics. They were fresh every day of the week. I could examine the work of dozens of cartoonists on a single page of newsprint. They had their own utterly unique visual vocabulary. (Sweat beads, motion lines and, yes, light bulbs.) And newspaper comics were free! Or so I thought. I wasn’t the one paying the paperboy.

I taught myself to draw by copying my favorite comic strip characters. (It was one of the great disappointments of my young life that I could never draw Charlie Brown’s head quite right. But I soldiered on.) As I grew older, I started creating comics of my own featuring self-invented characters like Super Jimmy, a bumbling superhero, and the Sea Scouts, a couple of clumsy park rangers. And—of course!—I began drawing rather mean-spirited cartoons depicting some of my teachers. My friends loved them (the drawings, not the teachers) and asked me to decorate their notebooks with my comics. It was intoxicating stuff for an aspiring cartoonist—until the day a particularly unpleasant math teacher discovered a drawing I’d done of her. I remember vividly the feeling of horror that washed over me as I watched her methodically crumple my masterpiece into a tiny ball. The worst part was that it happened on the third day of school. It ended up being kind of a long year.

There’s no doubt that Big Nate, the comic strip I created in 1991, grew out of these experiences and others like them. When I first submitted the strip for syndication, it was a family-based feature with an emphasis on domestic humor. But it didn’t take long for me to realize that, for both Nate and me, school was where the action was. I was pleased to discover that my memories of events from my own middle school career were very clear. No, I don’t remember anything about the Second Continental Congress or how to divide fractions. But I can summon up in almost photographic detail the vision of our music teacher, Ms. Brown, leading us in a spirited rendition of “Frankie & Johnnie,” oblivious to the fact that she’d split her pants when she’d sat down at the piano. I soon realized that those three years I spent at Oyster River Middle School in the mid-1970s were a comedic gold mine. Even after I’d become a high school art instructor years later, it was my own memories of schoolboy days, rather than my adult observations from a teacher’s perspective, that most directly informed the tone and tenor of Big Nate.

I love writing a comic strip. I am entirely at home within the daily framework of four identically-sized panels. Every day I get to create a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, usually in sixty words or less. But the format does have its limitations. Over the years I have often imagined what kinds of Big Nate stories I could tell if I had more time and space to work with. Now, happily, I’m finding out. Big Nate: In a Class by Himself is the book I’ve always wanted to write. Truth be told, it practically wrote itself. The story is entirely new, but the characters and themes featured in its pages are old friends to me. The book is an amplification of the smaller stories I’ve been telling in the newspapers for nearly 20 years. And here’s the part my inner middle-schooler really loves: there are drawings on every single page. I’d never written a book before, and the experience has been a revelation. Turns out I love writing books every bit as much as I’ve always enjoyed writing comics.

I’d call that another light bulb moment.

Visit Lincoln Peirce’s website at www.bignatebooks.com.

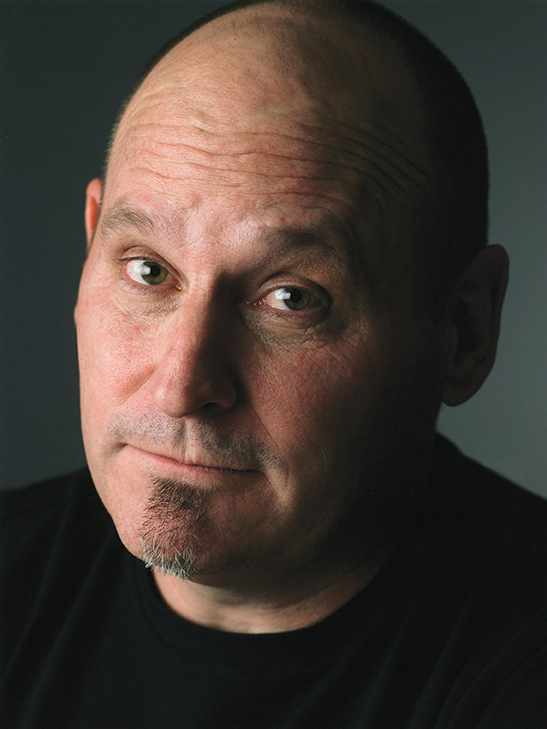

Lincoln Peirce photo courtesy of Jessica Gandolf.

By Kristin Tubb

By Kristin Tubb

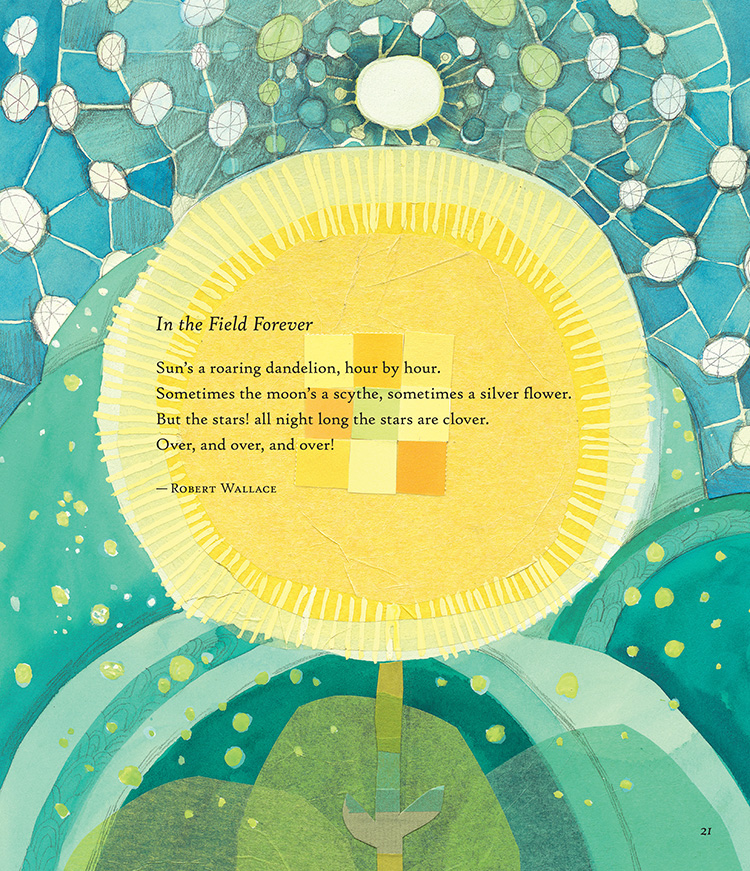

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.

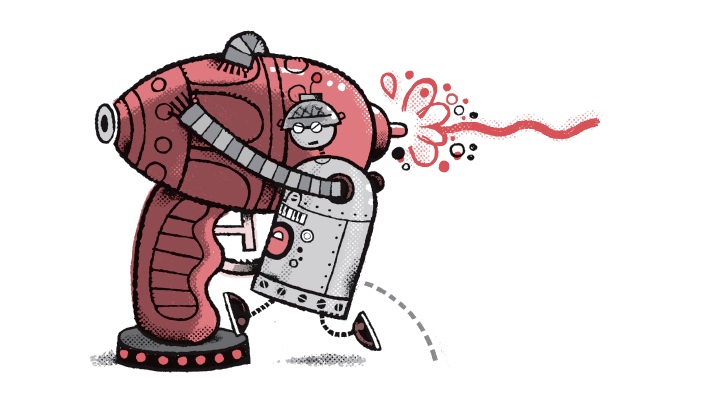

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.