It would take a whole lotta stamps to send an elephant in the mail, so young Sadie opts for a more personalized touch in Special Delivery, the new picture book romp from Philip C. Stead and Matthew Cordell. Sadie and her pachydermic package try a plane, a train and even an alligator in their postal voyage to Great-Aunt Josephine. As stamp collectors will recognize, the cover of Special Delivery is a nod to the famous Inverted Jenny stamp. Even more delightful are the book's end pages, which feature a great big pile of stamps, many of which seem to be inspired by classic children's literature. Cordell and Stead go behind their new book to share a bit more about the stamps in Special Delivery.

Matthew Cordell, illustrator

Matthew Cordell, illustrator

There is an awful lot going on in Special Delivery, but the book revolves around our determined hero, young Sadie, doing her darnedest to deliver (of all things) an elephant to her Great-Aunt Josephine. Sadie’s first instinct is to try and mail the big creature over and she tries this idea out at the Post Office with her postal clerk friend, Jim. Jim promptly lets Sadie know it will take a whole wheelbarrow-full of stamps to make this happen. This is one of my favorite moments in the book. I love this exchange and I love that it starts Sadie on her journey, but I also love the idea of all those stamps. I love stamps for their itsy-bitsy size, for their fun and sophisticated design and illustration, and for their historical significance. They have a sweet yet dignified nostalgic quality about them. And anyways, nothing says “Special Delivery” like a well-designed postage stamp.

The case cover (or “stamp-splosion” as I call it) was at first presented as an idea for illustrated endsheets. Whenever possible, as an added oomph of art, I like to squeeze in some well-thought illustrated endsheets into a picture book. But we were stretched thin as it was on the book’s page count. So Phil and I and our most excellent editor, Mr. Neal Porter, arranged for the stamp-splosion to stretch itself across the case cover, becoming a surprise eyeful of art hidden just beneath the book’s dust jacket. Incidentally, I knew there was going to be so much time needed to create that massive collage of stamps, that I decided to spend no time whatsoever in planning or sketching it out. When it came time to create the finished artwork, I just drew the entire thing as I went, in ink, from one end to the next. Which is very unusual for me. I typically plan and re-plan things in pencil sketches before finalizing all of my artwork. As I began drawing, I had very little idea what would be on any of these stamps other than characters or moments from the book itself. Much of it was stream of consciousness, but I ended up sneaking in a bunch of fun things including my wife and kids, my collaborators Phil and Neal, and several favorite classic picture book characters from years past.

The cover image materialized about midway into the sketching of the book. Phil and Neal and I were on the phone one afternoon having a great time discussing the first round of sketches, talking about what worked and what could yet be expanded upon to amp up the rambunctiousness of the whole thing. It was an incredibly productive and inspiring phone call that went on for over two hours. When I hung up the phone, my brain was buzzing. And it was at that exact moment that the image of the Inverted Jenny stamp popped into my head.

It was a perfect homage for this book’s cover. Not only does the book feature stamps, but there is also a sequence involving a wild ride in an old biplane. What wild ride in an old biplane would be complete without having turned the plane upside down? The 1918 stamp’s plane went upside down by accident, but in our case, it was all on purpose. I roughed it out as quick as I could and emailed the sketch over to Phil and Neal about 10 minutes after I’d hung up the phone. We all agreed that it simply couldn’t be any other way. Thankfully, by the time it came to print the book, everyone still agreed!

Philip C. Stead, author

Philip C. Stead, author

I've been a stamp collector since the fourth grade. So of course when Matt floated his idea for the "stamp-splosion" book case I said: Let's do it! For me, stamp collecting is all about the thrill of discovery. The diminutive size of most stamps only enhances that sense of discovery. Big and bizarre stories can be found in these tiny pieces of art.

For example, canine space travel!

Or how about this funny little creature? That's quite a sweater he's wearing!

And then there's this one. Hunting elephants from hot air balloons in a curious thing to do, but not so curious, I guess, that it doesn't warrant its own stamp. (Raise your hand if you're rooting for the elephant.)

I love sifting through piles of discarded stamps to find these gems. It's a similar feeling I get when browsing the bookstore or the library. The littlest discovery can expand my entire universe!

Philip C. Stead is the author of the 2011 Caldecott Medal book A Sick Day for Amos McGee. His book A Home for Bird received four starred reviews, while his most recent book, Hello, My Name Is Ruby, has earned three starred reviews. Philip lives with his wife, illustrator Erin E. Stead, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Check out his website.

Matthew Cordell created Trouble Gum, published by Feiwel and Friends. He has also illustrated several picture books, including Mighty Casey by James Preller and the Justin Case series by Rachel Vail. He lives outside Chicago with his lovely wife, the author Julie Halpern, their adorable daughter and their generally well-mannered cat. Check out his website and follow him on Twitter.

Images reproduced by permission of Roaring Brook Press. Check out Special Delivery at Macmillan.com.

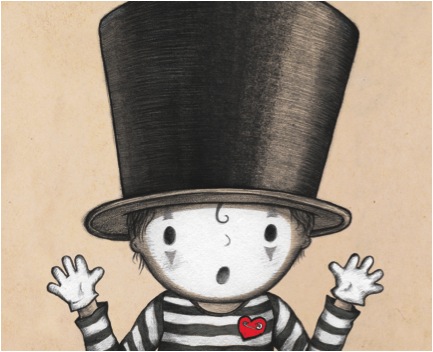

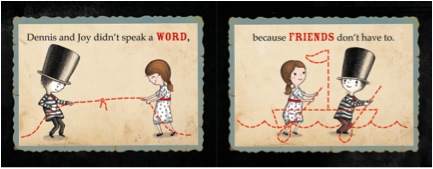

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled.

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled. On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.

On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.