Two new picture books with expertly crafted illustrations encourage young readers to venture off the path.

In Susanna Mattiangeli’s The Hideout, a young girl named Hannah decides to live in the park. Topping off her orange hair with a raccoon hat, Hannah sets up a shelter amid the dense foliage. She’s not alone, though. After finding an Odd Furry Creature, she shares her secret hideout, making them each a bed out of leaves and matching capes out of feathers.

Together, they relish their time in the wild, eating biscuit cookies, roasting pigeons on the campfire and collecting caterpillars, sticks and other bits. But what does this Odd Furry Creature even look like? Illustrator Felicita Sala’s intriguing watercolor and colored pencil illustrations slowly reveal its unusual features, from its talon fingers to its fluffy blue tail. Sala also conveys the differences between the quiet and increasingly overgrown vines of the hideout and the bustling activity in the rest of the park.

Although Hannah enjoys her undisturbed time with the Odd Furry Creature, she also realizes that time spent with dogs, balloons and people is also important. She leads her new companion out of the thicket and into the brightly lit park, but when an adult calls to her again, the story ends with Hannah back in her bedroom. With a fine blend of imagination and friendship, Hannah’s adventure is reminiscent of Where the Wild Things Are.

Once there was a river that flowed through a forest. But it didn’t know it was a river until Bear came along. When Bear’s tree-trunk perch snaps, it sends Bear floating down the river on the log, but he doesn’t know it’s the start of an adventure until Froggy hops on him. Thus begins Richard T. Morris’s uproarious Bear Came Along. The fun continues as Bear and Froggy are joined by the Turtles, Beaver, the Raccoons and Duck. Encouraged by the river’s twists and turns—and Beaver’s captain skills—they don’t know to be cautious until a waterfall comes along.

As the woodland animals hold onto one another, they survive the fall, enjoy the ride and realize that although they sometimes live separately, they all rely on one another. Illustrator LeUyen Pham’s watercolor, ink and gouache illustrations show the animals’ exaggerated expressions, which add to the hilarity and tension leading up to the waterfall, and the details in the patterned landscape offer an enriched reading experience.

The opening endpapers offer a black-and-white panoramic view of the story ahead. As children turn the pages, they’ll notice more and more colors as each animal arrives. The final scene and endpapers burst with colors as nature thrives together. Many humans will find plenty to learn about friendship and community from these spirited animals.

You Are Home

You Are Home Camp Tiger

Camp Tiger If I Were a Park Ranger by Catherine Stier, illustrated by Patrick Corrigan

If I Were a Park Ranger by Catherine Stier, illustrated by Patrick Corrigan

Papa Put a Man on the Moon by Kristy Dempsey, illustrated by Sarah Green

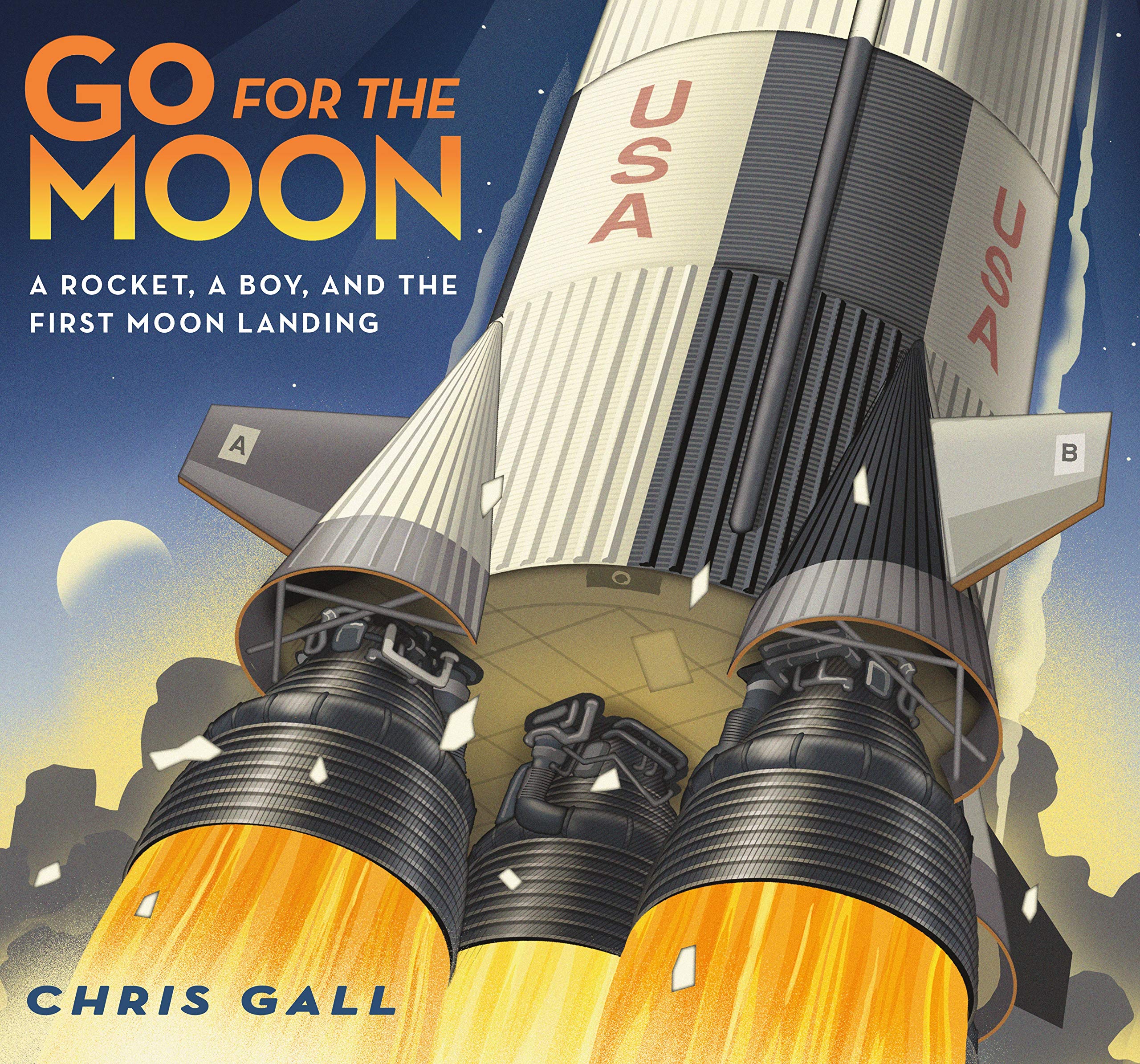

Papa Put a Man on the Moon by Kristy Dempsey, illustrated by Sarah Green Go for the Moon: A Rocket, A Boy, and the First Moon Landing by Chris Gall

Go for the Moon: A Rocket, A Boy, and the First Moon Landing by Chris Gall  Daring Dozen: The Twelve Who Walked on the Moon by Suzanne Slade, illustrated by Alan Marks

Daring Dozen: The Twelve Who Walked on the Moon by Suzanne Slade, illustrated by Alan Marks  The First Men Who Went to the Moon by Rhonda Gowler Greene, illustrated by Scott Brundage

The First Men Who Went to the Moon by Rhonda Gowler Greene, illustrated by Scott Brundage

Manhattan: Mapping the Story of an Island by Jennifer Thermes

Manhattan: Mapping the Story of an Island by Jennifer Thermes I Can Write the World written by Joshunda Sanders, illustrated by Charly Palmer

I Can Write the World written by Joshunda Sanders, illustrated by Charly Palmer  Nelly Takes New York written by Allison Pataki and Marya Myers, illustrated by Kristi Valiant

Nelly Takes New York written by Allison Pataki and Marya Myers, illustrated by Kristi Valiant

¡Vamos! Let’s Go to the Market by Raul the Third

¡Vamos! Let’s Go to the Market by Raul the Third My Papi Has a Motorcycle written by Isabel Quintero, illustrated by Zeke Peña

My Papi Has a Motorcycle written by Isabel Quintero, illustrated by Zeke Peña  One is a Piñata: A Book of Numbers written by Roseanne Greenfield Thong, illustrated by John Parra

One is a Piñata: A Book of Numbers written by Roseanne Greenfield Thong, illustrated by John Parra  Hummingbird written by Nicola Davies, illustrated by Jane Ray

Hummingbird written by Nicola Davies, illustrated by Jane Ray