Who are Americans, and what do they believe? How does our history shape our future? Six exceptional picture books explore our complicated, captivating country and offer meaningful perspectives on these vital questions about the great American experiment.

America, My Love, America, My Heart

In the author’s note of America, My Love, America, My Heart, Daria Peoples-Riley recalls growing up as “the only brown girl” at school, which made her feel like she wasn’t “free to be myself. . . . My country, America, didn’t feel free to me.” Her book is a glorious gift that will reassure children that they don’t have to change to accommodate people who don’t love every part of who they are.

In spare text accompanied by powerful images, Peoples-Riley conveys big, beautiful ideas. The first page depicts the narrator, a Black boy in a red shirt, his arms outspread, standing in a spotlight and looking down at his eagle-shaped shadow. “America, the Brave. America, the Bold,” writes Peoples-Riley.

From this striking opening, the book launches into a series of questions the boy asks his country. “Do you love me when I raise my hand? My head? My voice? When I whisper? When I SHOUT?” he wants to know. Complex legacies of injustice and activism are embedded in every question.

Peoples-Riley’s muted spreads contain splashes of red, white and blue that pop with pride on every page. Her illustrations portray people of various ages and many different skin tones. She employs a variety of settings, including vast fields, towering cityscapes and the interiors of churches and classrooms. The book builds toward a resounding challenge to embody the American ideal of inclusiveness: “America, Land of the Free. America, ’Tis of Thee. America, I am you. America, you are me.”

America, My Love, America, My Heart is exquisitely wrought and provides a perfect first glimpse at patriotism and equality.

We Are Still Here!

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Indian Appropriations Act, which effectively declared that Native tribes and nations were not sovereign entities with whom the federal government could form treaties. Indigenous people often disappear from American history curricula after this event. “We are still here!” is the resounding refrain of Traci Sorell and Frané Lessac’s excellent informational picture book, We Are Still Here!: Native American Truths Everyone Should Know.

Sorell, who is a dual citizen of the Cherokee Nation and the United States, has created an amazing repository of Native American history and presents it in an engaging, accessible manner. The book is her second collaboration with American-born Australian illustrator Lessac; their first, We Are Grateful: Otsaliheliga, received a Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award Honor in 2019.

The book’s title page shows a diverse group of students and their families entering the Native Nations Community School, where a clapboard by the door reveals that they’re celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Subsequent spreads represent student reports on topics such as assimilation, relocation and tribal activism. This framing device is a clever way to address many issues, with bright, colorful and kid-friendly illustrations depicting both the historical topics and the school scenes. Detailed back matter—which includes further information on each topic, an extensive timeline, a glossary, a bibliography and an author’s note—reveals the careful research that informs each spread.

An excellent resource, We Are Still Here! is an important book that highlights the sovereignty, strength and resilience of Native American peoples, tribes and nations despite centuries of mistreatment.

Areli Is a Dreamer

Areli Morales describes her personal experience growing up as an immigrant who came to America without legal permission in Areli Is a Dreamer: A True Story, a heartwarming, thoughtful and accessible introduction to contemporary immigration issues. The book will be simultaneously published in a Spanish-language edition, translated by Polo Orozco.

Morales excels at gently conveying the emotional challenges of her story. Readers meet young Areli when she and her older brother, Alex, are living with their abuela in Mexico. Areli’s parents, who have already immigrated to New York, have “been away so long, they felt like strangers.” When Areli finally joins them, she is heartbroken at leaving her grandmother and friends behind but thrilled to be reunited with her family.

However, Areli’s new city is intimidating, and her classmates tease her and call her “an illegal.” When her mother explains that without legal documentation, Areli can be sent back to Mexico and can’t become a citizen, she struggles to understand. She begins to grasp the significance of her journey during a field trip to Ellis Island. In a memorable spread, Areli gazes at the Statue of Liberty and envisions a boat full of immigrants. “She did not feel illegal,” Morales writes. “She felt like she was part of something very big.”

Despite the hardships and uncertainty that Areli experiences, Luisa Uribe’s illustrations portray scenes of Areli’s family, as well as her changing surroundings from Mexico to New York, in a lively, reassuring way. An energetic scene of July Fourth fireworks conveys Areli’s feelings of acceptance in her new home, while a visual motif of stars highlights her hopes and dreams for a bright future.

Areli Is a Dreamer speaks to the fears and difficulties of immigration in a well-told story that never loses sight of its young heroine’s hopes and dreams. It’s a touching portrait of a loving, determined family as they deal with uncertainty and discover what it means to be American.

A Day for Rememberin’

A Day for Rememberin’ is a fictionalized account of the incredible events that occurred in Charleston, South Carolina, on May 1, 1865. In one of the first known observances of Decoration Day, now known as Memorial Day, 10,000 formerly enslaved people, along with other members of the community, decorated the graves of 257 Union soldiers who died and were buried at a racetrack that had been used as a Confederate prison during the Civil War.

Leah Henderson tells this story through the eyes of 10-year-old Eli. In lively prose, she incorporates details about Eli’s family at this critical juncture in American history. Eli’s parents had been enslaved. His mother secretly taught herself to read and tells her son that he has the “hard-earned right to learn and what it’s gonna get you beyond.” On this special day, Eli is proud to be chosen to lead a procession of children to the graves because he’s “fastest at learning [his] numbers and letters.”

Using warm sepia tones, Coretta Scott King Award-winning illustrator Floyd Cooper brings the newly freed people in Eli’s community to life, filling their faces with expressions of determination, remembrance, mourning and celebration. Henderson’s writing is specific and energetic, from the roses and hawthornes carried by Eli’s classmates to his mother’s calico dress to Eli’s description of leading the parade: “Right out in front, I stomp, knees high.”

A Day for Rememberin’ relates a fascinating, little-known historical event with a moving story about slavery, freedom and the importance of honoring those who sacrifice their lives for others. Sumptuously told and illustrated, it’s likely to be long remembered.

Twenty-One Steps

“I am Unknown. I am one of many,” declares the narrator of Twenty-One Steps: Guarding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Author Jeff Gottesfeld writes from the perspective of the first soldier to be interred at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. His book describes the monument’s history, the rigor of the highly select group of people who serve as guards and the meticulous changing of the guard ceremony.

This is by no means an easy subject for a picture book, but Gottesfeld navigates the tricky turf well. Though his focus is on the Tomb itself, the specter of “combat’s vile fury” hangs over many of the spreads. In an appropriately elegiac tone, the text delicately evokes a range of emotions and images, including the horrors of World War I’s bayonets and mustard gas, the grief of surviving family and friends, and the admiration and remembrances of those who flock to the monument to “marvel at our sentinels.”

Illustrator Matt Tavares knows his way around American history, having previously illustrated books about Benjamin Franklin, Helen Keller, John F. Kennedy and even the Statue of Liberty. He begins with an engaging close-up of a framed photograph of a Black soldier, suggesting what the unknown soldier interred in the Tomb might look like. His illustrations show the Tomb during the day and at night, in snow, sleet and under bright skies, emphasizing the unwavering presence of its guards.

Twenty-One Steps is such a vivid tribute that readers will practically hear the rhythmic click of the guards’ heels as they walk back and forth, a measured reminder of the loss and sacrifice the Tomb represents.

This Very Tree

Native New Yorker Sean Rubin tells the story of a Callery pear tree that survived the September 11 terrorist attack on his city in This Very Tree: A Story of 9/11, Resilience, and Regrowth, transforming the tree’s story into a beautiful allegory about trauma and healing.

Writing from the tree’s perspective, Rubin describes the moment of the attack in plainspoken language: “It was an ordinary moment. Until it wasn’t.” A multipanel spread shows glimpses of stunned onlookers’ faces, the pants and shoes of people running away, debris, smoke and flames, followed by a spread that shows the tree buried beneath a mountain of twisted black and gray metal. “Around me it was dark and hot and close. Did the sun even exist anymore?” the tree recalls. After being pulled from the wreckage, the tree is taken to a nursery, where it spends nine years healing. Ultimately the tree is returned to the plaza at the Sept. 11 memorial.

The process of excavating, rescuing and bringing the tree back to life is likely to fascinate young readers. A spread of eight panels reveals parallel stages in the construction of One World Trade Center and the tree’s regrowth. Rubin’s text often includes emotional details that will help readers relate to the tree’s journey. As it’s transported back through the city, the tree reveals that it’s worried. “What if something bad happened again?” Rubin keeps the story simple and focused, relying on ample back matter to provide curious readers with further information. It makes for a stirring story of hope and healing in the aftermath of immense tragedy.

Make Meatballs Sing: The Life & Art of Corita Kent

Make Meatballs Sing: The Life & Art of Corita Kent Unbound: The Life and Art of Judith Scott

Unbound: The Life and Art of Judith Scott

The Ramble Shamble Children

The Ramble Shamble Children When My Cousins Come to Town

When My Cousins Come to Town The House of Grass and Sky

The House of Grass and Sky

Becoming Vanessa

Becoming Vanessa Norman’s First Day at Dino Day Care

Norman’s First Day at Dino Day Care I Can Help

I Can Help Henry at Home

Henry at Home

As a child in Puerto Rico, Pura Belpré learns Puerto Rican folktales from her grandmother. When Belpré immigrates to New York City, she takes her abuela’s stories with her. In busy, bustling Harlem, Belpré loves her job at a library. But when she decides to share the stories she learned as a child—stories that have not been published and therefore are not approved by the library—she begins a journey that will change storytelling forever. Pura’s Cuentos: How Pura Belpré Reshaped Libraries With Her Stories is an enchanting look at a woman who left an indelible mark on children’s literature.

As a child in Puerto Rico, Pura Belpré learns Puerto Rican folktales from her grandmother. When Belpré immigrates to New York City, she takes her abuela’s stories with her. In busy, bustling Harlem, Belpré loves her job at a library. But when she decides to share the stories she learned as a child—stories that have not been published and therefore are not approved by the library—she begins a journey that will change storytelling forever. Pura’s Cuentos: How Pura Belpré Reshaped Libraries With Her Stories is an enchanting look at a woman who left an indelible mark on children’s literature. Like Belpré, Luz Jiménez was a storyteller, but she was also an artists’ model, teacher and advocate for the Nahua, the native people of Mexico. Born in 1897, Jiménez learned the Nahua language, traditions and stories and longed to share them with the world. Written by Gloria Amescua and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh, Child of the Flower-Song People is a reverential portrait of a woman who never lost sight of her dreams.

Like Belpré, Luz Jiménez was a storyteller, but she was also an artists’ model, teacher and advocate for the Nahua, the native people of Mexico. Born in 1897, Jiménez learned the Nahua language, traditions and stories and longed to share them with the world. Written by Gloria Amescua and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh, Child of the Flower-Song People is a reverential portrait of a woman who never lost sight of her dreams. Some storytellers use words to entertain listeners and readers, while others share their tales in song. Nina: A Story of Nina Simone gracefully brings the life of one such legendary musician into readers’ hearts.

Some storytellers use words to entertain listeners and readers, while others share their tales in song. Nina: A Story of Nina Simone gracefully brings the life of one such legendary musician into readers’ hearts.

Little Bat in Night School

Little Bat in Night School Bird Boy

Bird Boy This Is Ruby

This Is Ruby

Dumplings for Lili

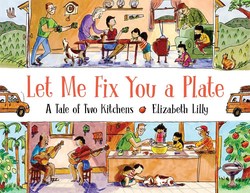

Dumplings for Lili Let Me Fix You a Plate

Let Me Fix You a Plate Soul Food Sunday

Soul Food Sunday

Have You Seen Gordon?

Have You Seen Gordon? Vampenguin

Vampenguin The Little Wooden Robot and the Log Princess

The Little Wooden Robot and the Log Princess