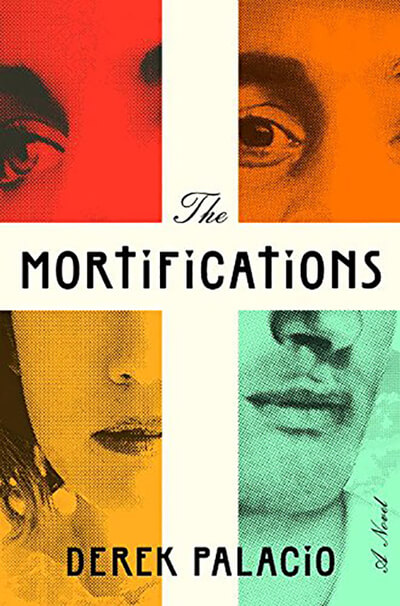

The Mortifications, Derek Palacio’s beautifully written debut novel, begins in 1980, during the Mariel boatlift that took refugees from Cuba to the United States. Soledad Encarnación packs her 12-year-old son, Ulises, and his twin sister, Isabel, onto an overcrowded lobster boat that carries them away from their village of Buey Arriba. Her husband, Uxbal, chooses to stay behind, but not without first trying to prevent his family’s departure by holding Isabel ransom.

In Connecticut, Soledad becomes a court stenographer and attracts the attention of lawyers who find her exotic. She falls in love with Henri Willems, a Dutch horticulturalist who grows Cuba’s Habano tobacco in the Connecticut River Valley.

At 17, Ulises, a budding Latin scholar, gets a job working in Henri’s fields. The more devout Isabel volunteers with the terminally ill at Jude the Apostle. Soon, she takes a vow of chastity and silence and leaves for Guatemala to establish a school funded by the church. And all of this is before Soledad’s diagnosis of breast cancer and a letter from Uxbal, who demands his family’s return to Cuba.

The Mortifications is a devastating portrait of the realities we construct for ourselves, the parts of our history we choose to embrace and those we yearn to escape. In deceptively simple prose, Palacio writes movingly of dreams and family legacies and reminds us that, no matter how far away you travel, some aspects of one’s ancestry are forever a part of you.

This article was originally published in the October 2016 issue of BookPage. Download the entire issue for the Kindle or Nook.