Lincoln’s legacy lives on Abraham Lincoln was born in February of 1809, in humble surroundings. When he was assassinated 56 years later, he was one of the most famous human beings on earth. Even Uncle Sam himself had gradually evolved into a Lincolnesque figure. To this day Lincoln is the supreme deity in American mythology, and his profile on the penny is the most frequently reproduced portrait in the world. In an author’s note at the front of Lincoln: A Foreigner’s Quest (Simon ∧ Schuster, $23, 0684855151), Jan Morris offers respectful and apologetic gratitude to the living and dead scholars upon whose work she built her own. Perhaps they should thank her instead. Many historians have written about Lincoln, but few have brought the man and his times alive so vividly as Morris does in this 200-page book. She waves her imagination across the dry old facts and they stand up and dance.

Jan Morris first visited the United States during the 1950s, when Lincoln idolatry was at its peak. Over the years Morris remained skeptical but intrigued. Finally, in the late 1990s, she visited contemporary Springfield, researched the city as it was in Lincoln’s time, and wrote about both experiences. She did the same with Gettysburg and Washington and the prairie countryside. The result is this splendid book.

Lincoln rose above his humble origins by becoming a lawyer and a legislator. According to Morris, Lincoln, like many ambitious politicians, made shady deals, rewarded patronage, and made empty promises. Only later, as president, when he had nowhere else to climb and his perpetual melancholy and Shakespearean outlook grew into a sense of destiny, did he rise to the occasion and become an Emersonian great man. Morris’s account of this personal growth is riveting. Although Lincoln never lost his taste for cheap jokes, gradually he replaced the stilted rhetoric of his early years with sinewy prose of almost Elizabethan grandeur.

Morris’s description of slavery also helps bring to life the era and its issues, from the horrors of punishment to the appeal of the genteel slave-based culture of the South. Although in time he opposed slavery, Lincoln considered blacks decidedly inferior and dreamed of their repatriation to their native lands or segregation in a separate colony. Skeptical at first, always objective, Morris nonetheless grew to like her subject. Ultimately she decides that the contradictory aspects of Lincoln’s personality may be resolved by accepting that he was by nature as much an artist as anything else. The moods, the contradictions, the evasiveness, the questioning of accepted truths, the playacting, the sexual complexity, the sad resolution, and the power to move the spirit, all made a poet of this consummate politician. Two other new books address Abraham Lincoln in ways dramatically different ways from Morris’s approach. Historian and novelist Richard Slotkin has written a novel about Lincoln’s upbringing and early years, titled simply Abe. It is an adventurous, violent, and yet thoughtful melodrama based in historical research but not strangled by it.

Usually Slotkin has a light touch that brings the man alive without dressing him up as the myth. This skill shows especially in such scenes as the teenage Abe working on his reading skills, even when he pores over a book that contains the Declaration of Independence. After all, reading really was Lincoln’s salvation, and his first inklings of the power of language and the language of power came from the already sacred American gospels. Slotkin nicely renders the requisite Huck Finn scenes, such as Abe’s momentous journey down the Mississippi. However, there are moments when the author’s admiration for his hero gets out of hand. At one point Slotkin’s teenage Abe is mistaken for a high yaller octoroon and actually quotes Shylock’s Hath not a Jew eyes? speech with references to slaves replacing those to Jews. Jan Morris is skeptical about the mythological Abraham Lincoln, and Richard Slotkin’s narrative urge is inspired by both the myths and the facts. Another new book examines the ways in which Lincoln’s powerful figure captured the imagination of Hollywood and other purveyors of popular culture. Abraham Lincoln: Twentieth-Century Popular Portrayals, by Frank Thompson (Taylor, $26.95, 0878332413), is a curious labor of love. Thompson has thoughtfully examined every movie about Lincoln, including silents, and also the many portrayals on television. After all, the cinematic Lincoln ranges the spectrum from Henry Fonda’s Young Mr. Lincoln to comic appearances in Police Squad and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure. Through this surprisingly entertaining tour, Thompson evaluates the popular status of Abraham Lincoln. Apparently the myth is alive and well.

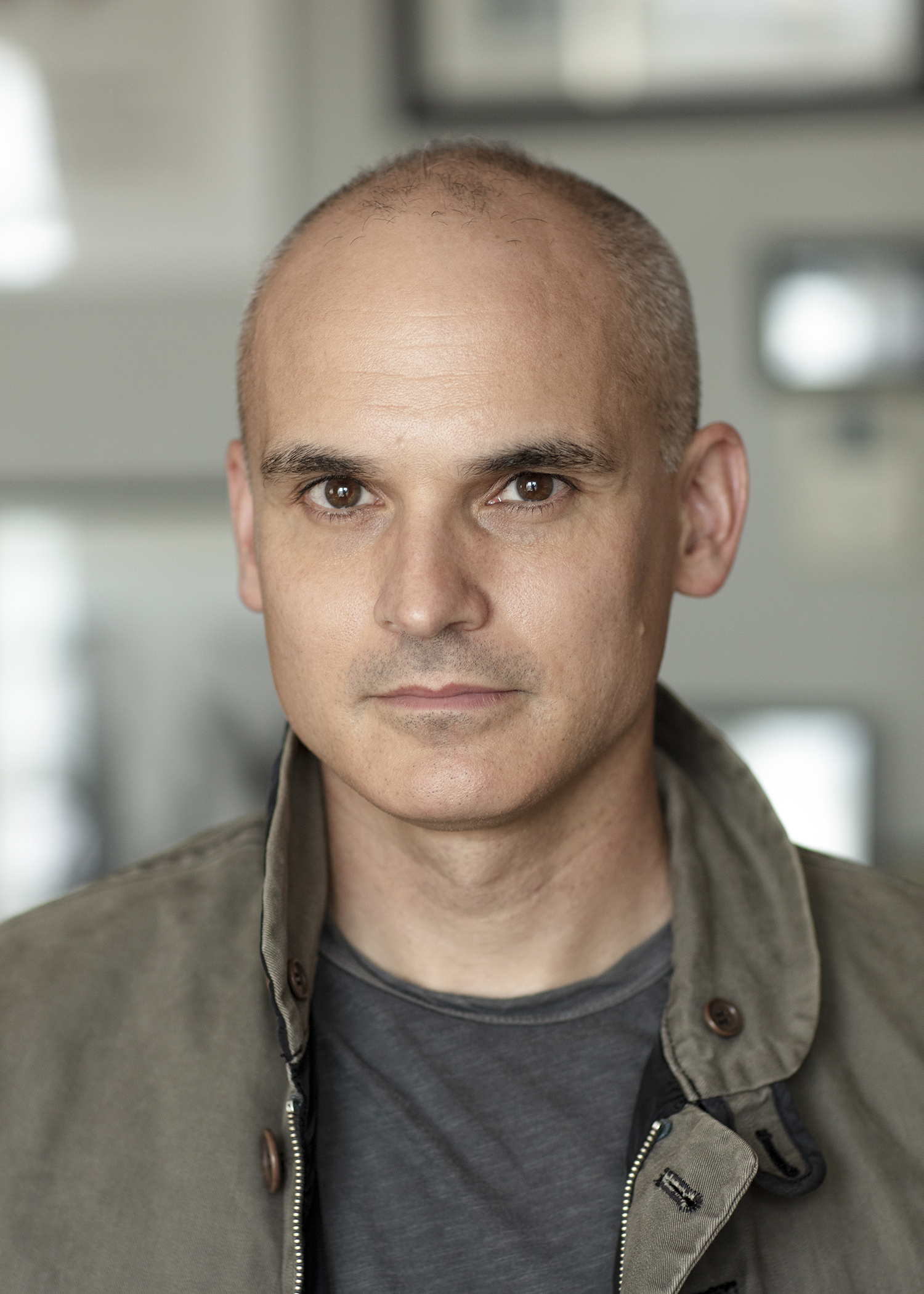

Michael Sims is the author of Darwin’s Orchestra (Henry Holt).