We begin each new reading year with high hopes, and sometimes, when we’re very lucky, we find our expectations rewarded. So it was with 2021.

It must be said that a lot of these books are really, really long. Apparently this was the year for total commitment, for taking a plunge and allowing ourselves to be swallowed up.

Also, it should come as no surprise that books-within-books frequently appear on this list. For all our attempts at objectivity within our roles as critics, we just can’t help but love a book that loves books. Amor Towles, Ruth Ozeki, Jason Mott, Maggie Shipstead and Anthony Doerr all tapped into the most comforting yet complex parts of our book-loving selves.

But most of the books on this list hit home in ways we never could’ve prepared for, even when we had the highest expectations, such as in Will McPhail’s graphic novel, which made us laugh till we cried, and Colson Whitehead’s heist novel, which no one could’ve expected would be such a gorgeous ode to sofas.

And at the top of our list, a book that accomplishes what feels like the impossible: Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ epic debut novel, which challenges our relationship to the land beneath us in a way we’ve never experienced but long hoped for.

Read on for our 20 best works of literary fiction from 2021.

20. What Comes After by JoAnn Tompkins

In JoAnne Tompkins’ debut novel, faith is simply part of life, a reality for many that is rarely so sensitively portrayed in fiction.

19. How Beautiful We Were by Imbolo Mbue

To those disinclined to question the role that economic exploitation plays in supporting our modern lifestyle, reading this novel may prove an unsettling experience.

18. Gordo by Jaime Cortez

In his collection of short stories set in the ag-industrial maw of central California, Jaime Cortez artfully captures the daily lives of his characters in the freeze-frame flash of a master at work.

17. Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro continues his genre-twisting ways with a tale that explores whether science could—or should—manipulate the future.

16. Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

Francis Spufford’s graceful novel reminds us that tragedy deprives the world of not only noble people but also scoundrels, both of whom are part of the fabric of history.

15. Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen

Jonathan Franzen is one of our best chroniclers of suburban family life, and his incisive new novel, the first in a planned trilogy, is by turns funny and terrifying.

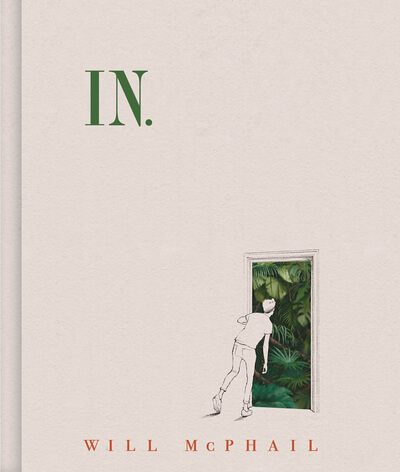

14. In by Will McPhail

Small talk becomes real talk in this graphic novel from the celebrated cartoonist, and the world suddenly seems much brighter.

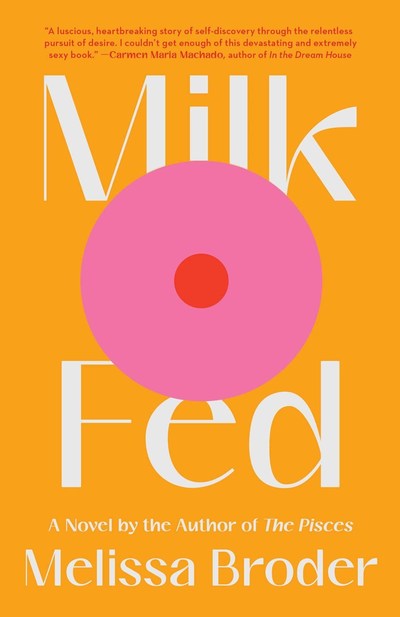

13. Milk Fed by Melissa Broder

With hints of Jami Attenberg’s sense of mishpucha and spiced with Jennifer Weiner’s chutzpah, Melissa Broder’s novel is graphic, tender and poetic, a delicious rom-com that turns serious.

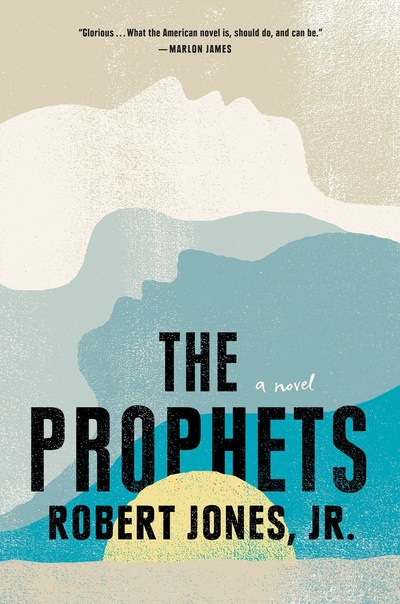

12. The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr.

Robert Jones Jr.’s first novel accomplishes the exceptional literary feat of being at once an intimate, poetic love story and a sweeping, excruciating portrait of life on a Mississippi plantation.

11. Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson

In her exceptional debut novel, Ash Davidson expresses the heart and soul of Northern California’s redwood forest community.

10. The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

“There are few things more beautiful to an author’s eye . . . than a well-read copy of one of his books,” says a character in Amor Towles’ novel. Undoubtedly, the pages of this cross-country saga are destined to be turned—and occasionally tattered—by numerous gratified readers.

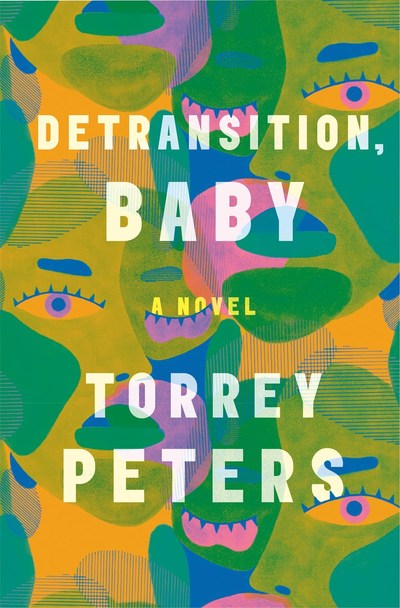

9. Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

Devastating, hilarious and touching, Torrey Peters’ acutely intelligent first novel explores womanhood, parenthood and all the possibilities that lie therein.

8. A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Peter Ho Davies’ third novel is a poetic look at the nature of regret and a couple’s enduring love. It’s a difficult but marvelous book.

7. The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

What does it mean to listen? What can you hear if you pay close attention, especially in a moment of grief? Ruth Ozeki explores these questions in her novel, a meditation on objects, compassion and everyday beauty.

6. Matrix by Lauren Groff

Lauren Groff aims to create a sense of wonder and awe in her novels, and in her boldly original fourth novel, set in a small convent in 12th-century England, the awe-filled moments are too many to count.

5. Hell of a Book by Jason Mott

A surrealist feast of imagination that’s brimming with very real horrors, frustrations and sorrows, Jason Mott’s fourth novel is an achievement of American fiction that rises to meet this particular moment with charm, wisdom and truth.

4. Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

Sorrow and violence play large roles in the ambitious, genre-busting novel from Pulitzer Prize winner Anthony Doerr, but so does tenderness.

3. Harlem Shuffle by Colson Whitehead

Like Dante leading us through the levels of hell, Colson Whitehead exposes the layers of rottenness in New York City with characters who follow an ethical code that may be strange to those of us who aren’t crooks or cynics.

2. Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

In her exhilarating third novel, Maggie Shipstead offers a marvelous pastiche of adventure and emotion as she explores what it means (and what it takes) to live an unusual life.

1. The Love Songs of W.E.B Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

From slavery to freedom, discrimination to justice, tradition to unorthodoxy, celebrated poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers weaves an epic ancestral story that encompasses not only a young Black woman’s family heritage but also that of the American land where their history unfolded.