Growing up in Vienna during the Great Sausage Famine, it was out of pure necessity that my family developed a very strong tradition of telling stories around the fire. And, because we did not have a fireplace, most of those stories were about how to escape a burning building.

Still, it’s a rather substantive leap from coughing out a narrative as you crawl on your hands and knees toward the nearest exit to actually writing a book. And, thus, it took me years before I would finally get around to doing just that. I would first need both a good story to tell and the motivation to tell it.

The latter would come as I was lounging around my luxurious mansion taking account of what items I might like to purchase that day with some of the many millions of dollars I’ve earned over the years as founder and president of the National Center for Unsolicited Advice. I compiled a list of goods that included a pound of peanut butter nougat-flavored coffee beans, a new Mayan swimsuit calendar, and a boxed set featuring the best of Celtic banjo music. And where would I find all these items? Why at a bookstore, of course.

It was while strolling through my friendly neighborhood bookstore, searching through the calendar section, that I spied, high upon one of the many shelves of books, a very conspicuous empty slot. Needless to say I was appalled and it occurred to me rather immediately that someone needed to write something quickly in order to fill that awful black hole of booklessness. And that person, I decided, should be Nathaniel Hawthorne. I then remembered that Nathaniel Hawthorne is dead, so I quickly undecided and then redecided that I would be the one to step up and do all that was necessary to rid that poor shelf of its awful void.

I had my motivation but did I have a story to tell and, more importantly, would my story be worthy of that coveted slot between War and Peace and Wart Removal For Dummies? After all, the last thing I wanted was to write a book that would find itself lying on a table beneath a sign reading, “Books for under three dollars” or” Books: twelve cents a pound” or “Free kindling.” Actually the last thing I wanted was to be eaten alive by a swarm of larger-than-average ants. Still, authoring an uninteresting book was fairly high on the list of things I did not want to happen.

Before writing a single word I would have to make certain that I had a story that would grab readers by the throat and . . . shake them vigorously resulting in an arrest for assault and a lengthy prison sentence during which time it would learn a trade (metallurgy, let’s say) and eventually be released on parole and become a productive member of society and perhaps write a book of its own, which it would promote on talk shows all over the country. That’s the kind of story I needed. But where would I find such a tale?

Well, as fate would have it, fate intervened on that fateful day. I drove home from the bookstore, the delightful aroma of peanut butter nougat filling the car as Celtic banjo music tested the very limits of the sound system. Upon my arrival, I opened my mailbox. Tucked between yet another request for money from Rutherford, my evil step twin, and a coupon for $1 off on a pizza made entirely of cheese, I was delighted to find a postcard featuring a photo of the World’s Largest Hat. Flipping the postcard over to its non-giant-hat side, I saw that it was from my good friend, Ethan Cheeseman.

An old college chum from Southwestern North Dakota State University, I hadn’t heard from Ethan in many years. While I was building an empire of unsolicited advice, he and his lovely wife, Olivia, were busy having children and working on perfecting his many brilliant inventions.

As I read his words I soon realized that my good fortune was Ethan’s worst nightmare. I was shocked and devastated to learn that Olivia had been murdered by evil villains (for my money, the worst kind of villains), forcing Ethan and his three smart, polite, attractive and relatively odor-free children to go on the run. If something should happen to him or to the children, he wanted to make sure his story was told. I was honored that he had entrusted that duty to his old friend, Bertie, as I was known in those heady days at good old SWNDSU.

I began receiving postcards on a regular basis, sometimes as many as four or five per week, each one relaying in detail Ethan’s desperate attempt to stay one step ahead of an ever-growing number of pursuers while he worked to perfect his greatest invention; one he hoped could be used to save the life of the woman he and his children loved so dearly.

And so I began the arduous task of turning a ton of postcards and letters (which may weigh the same as a ton of bricks but takes up a lot more room) into A Whole Nother Story. My progress was slow. You see, unlike most writers today, I do not use a computer. I write the old fashioned way; on the walls of caves. (Unlike computers, they rarely crash.) Using a blend of seven different berries smooshed together, the end result is, perhaps, the only book you will ever read that is made with 10% real fruit juice. In addition to being rich in vitamins A and C, it is my hope that it is also the story I had been looking for; one that will grab readers by the throat or, at the very least, tap them on the shoulder and say, “Psst, up here.”

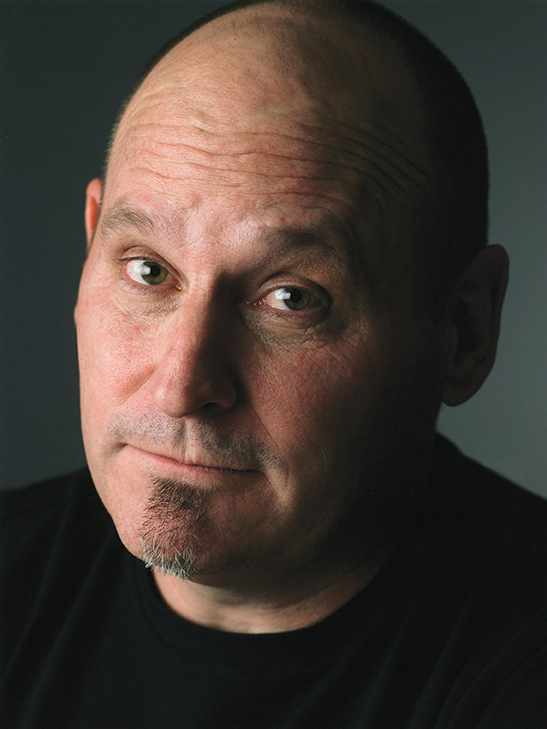

Dr. Cuthbert Soup was born in Vienna, Austria at the height of the Great Sausage Famine. At 23 he dropped out of high school and moved to New York City where he landed a gig playing elevator music. He was soon fired, however, as his trombone kept smacking other people in the elevator. Six years later, with not a penny to his name, his changed his name to Delvin but quickly changed it back again and opened the National Center for Unsolicited Advice. Since then, he has served as an unofficial advisor to CEOs, religious leaders and heads of state and has given countless inspirational lectures to unsuspecting crowds. In his spare time he enjoys cajoling, sneering and practicing the trombone in crowded areas. Dr. Soup currently resides in a semi-secret location somewhere in the United States. A Whole Nother Story is his first book; its companion, A Whole Nother Whole Nother Story, will be released in January 2011. www.awholenotherbook.com

By Kristin Tubb

By Kristin Tubb

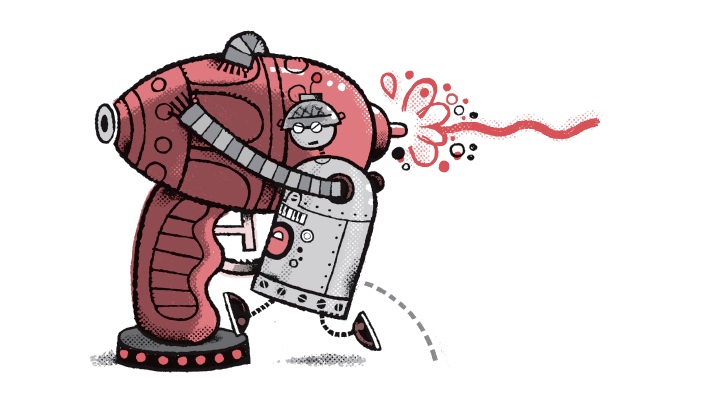

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.

Oh, and my other favorite scene is when Klank attacks Edison’s Antimatter Squirt Gun. This thing is powerful enough to destroy Einstein and Watson and both robots. And though Klank isn't the smartest robot in the world, he does have the biggest robot heart. And Brian's illustrations show exactly what happens.