Sara Nickerson's new middle grade novel is full of summery secrets, but the inspiration behind The Secrets of Blueberries, Brothers, Moose & Me is an open book. Nickerson takes us to the blueberry-picking days of her childhood.

When I was a kid I wanted to live inside books. I wanted to test myself, face hardships, survive fever 'n' ague. I read Heidi with bread and cheese in my hand. It was regular sliced bread and Thriftway cheddar, but when I ate it, I felt surrounded by mountain air and sunshine. After reading My Side of the Mountain, I mapped my solo escape to the wilderness and spent hours working to trap small animals with a cardboard box and string. To this day I can’t read Farmer Boy without gaining five pounds.

Around that same time, the time of living inside books, I got my first job. My older brother, wanting better school clothes, came up with the idea to pick blueberries. My younger brother and I, obsessed with the awesome things you could order from the backs of comic books, begged to come along. Our mother, busy with two baby brothers, was not hard to convince. We were living in Olympia, Washington, and the blueberry farm was miles past town. Like the farm in my novel, there were feuding farmer brothers, one on either side of a giant hedge. On that first day we were warned: Never go on the other side. I felt the thrill of a real-life adventure.

"Most of all, we treasured the blueberry field because it belonged to us. We weren’t at day camp or a playground or even in the woods behind our house. We’d moved past the boundary of our mother’s voice."

There were other kids in the field, of course, but also grown-ups. We were out there together, sharing an outhouse, and not the modern kind with hand sanitizer. There was mystery in the blueberry field, and romance. There was a girl who would stick a blueberry in her belly button and do the hula. This job, picking blueberries, was a hot and sweaty torture. My brothers and I hated it, we loved it, we were obsessed by the money of it and made lists of the things we would buy, like colonies of Sea Monkeys and giant inflatable beer bottles. Most of all, we treasured the blueberry field because it belonged to us. We weren’t at day camp or a playground or even in the woods behind our house. We’d moved past the boundary of our mother’s voice. Finally, finally, I had stepped into the pages of my very own book.

The Secrets of Blueberries, Brothers, Moose & Me takes place during that summer when everything changes. Twelve-year-old Missy and her older brother Patrick are on their own, making painful mistakes and amazing discoveries. It’s not the story my brothers are expecting to see. They probably won’t recognize my main characters. They’ll miss the dirt clod fights and the old lady named Bernice, who sat on an overturned bucket and couldn’t stop talking, even when no one was around. They’ll miss the dirty jokes, the ones I couldn’t understand but made a point to memorize for the day that I could. They’ll miss the groups of migrant families, who did this work for real.

What my brothers will recognize is the feeling we had out there. We were part of the big wide world. I remember walking into a grocery store a week after I’d started the picking job. I stood in the produce aisle and thought: This is food. It doesn’t just come from a store. I know where it comes from.

For the kids who live inside books, I hope this one will make them want to go outside and look at dirt, even if it’s between the cracks in the sidewalk. Follow an ant’s crazy path, or try to tell time from the sun. Hold an apple or a blueberry or a peach, even one from a can, and wonder where it came from—where it really came from. And maybe feel a new connection to their very own big wide world.

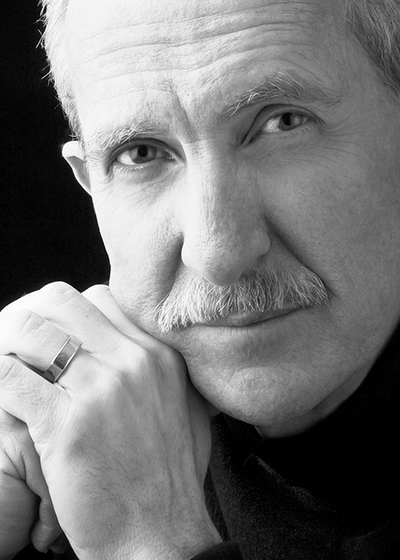

Author photo credit Ingrid Pape.