All I want for Christmas this year is a box full of kids’ gift books. That’s exactly how I feel after perusing these inspiring selections, which include visual, musical and artistic treasures, plus boatloads of fun and games.

ALL ABOARD THIS BOOK

Preschoolers will eagerly hop aboard Train: A Journey Through the Pages Book, Mike Vago and Matt Rockefeller’s sure-to-be-a-hit creation. Young engineers can steer a small plastic steam engine across “tracks” built into the book’s pages, starting early in the morning in a train yard and traveling through a city full of skyscrapers, hillside towns, snow-capped mountains, wide-open prairies, a parched desert and a cheerful seaside bay. Colorful illustrations in this changing American landscape offer the feel of a cross-country journey as the train travels over rivers and navigates mountainous curves.

Clever construction allows the train to stay on its “tracks,” moving seamlessly from page to page. Finally, at the end, a tunnel built into the book allows train lovers to start their journey all over again.

A YEAR OF LEGO FUN

Does your LEGO lover need inspiration? From the creative team that developed the bestselling The LEGO Ideas Book and LEGO Awesome Ideas comes 365 Things to Do with LEGO Bricks. It’s packed with a variety of activities, games, challenges and pranks that will appeal to everyone from elementary students to young-at-heart grown-ups. A small timer allows builders to race against the clock during select challenges, or use its random number generator to decide which project to pursue.

This is not a book for beginners, nor does it offer step-by-step instructions, but the projects are incredibly varied, colorful and appealing. Build an animated bear’s head or a model of your bedroom. Put on a magic show, or film your own LEGO movie. Construct a small pinball machine, a shark that bites or a carnival shooting gallery. This is creativity at its best, and it’ll keep your builder busy all year long.

MUSIC TO YOUR EARS

Kids tend to love “sound books,” but endless pushing of those buttons can quickly drive parents over the brink. Not so with Katie Cotton’s The Story Orchestra: Four Seasons in One Day, the story of a girl and her dog set to the sounds of Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons,” the first in a series of books to bring classical music to life for kids.

As readers follow young Isabelle and her dog, Pickle, through the year, beginning with a Spring Festival and ending on a snowy winter’s eve, buttons on each spread play snippets of movements from Vivaldi’s opus. Artwork by Jessica Courtney-Tickle is a gorgeous riot of color and detail, guaranteed to hold readers’ interest as they listen to the music.

An informative spread at the end contains a capsule biography of the composer, a short glossary and brief explanations of the music featured on each spread. The Story Orchestra is an innovative little master class for young listeners.

BRINGING ART TO LIFE

What might Vincent van Gogh have been thinking about when he was about to paint one of his most famous masterpieces? Elementary school students will be in the know after reading Vincent’s Starry Night and Other Stories: A Children’s History of Art, a creative and comprehensive look at masterworks from cave paintings to Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei.

Art historian Michael Bird brings 68 stories to life using fact-filled creative nonfiction. For instance, Bird describes Jackson Pollock’s creative process through the eyes of the artist’s wife: “He dips a wooden stick into another pot, and flicks and drips the paint—here, there, too quick for thinking. All the time, he strides and kind of dances around the canvas, bent over it, a magician casting a spell.”

Each chapter offers an intriguing and informative tale and is accompanied by a photograph of the artwork being discussed, as well as Kate Evans’ evocative illustrations of the artist at work. This lovely book is rounded out by a map, timeline, glossary and list of artworks.

ABRACADABRA

There is no end of children’s magic kits and books, but The Magic Show Book has everything young illusionists need, including props, pop-up tricks and materials to make your own special “shrinking” magic wand—a trick in itself. (Parents will particularly appreciate this self-contained aspect.)

Each colorful page includes a flap with hidden instructions showing how to practice and perfect tricks such as “Tricky Chicken,” “The Astonishing Slicer” and “Eyes on the Ace.” Additional pages explain a variety of rope (shoelace), coin and card sleights of hand. There’s even a pop-up magic hat.

The Magic Show Book is bound to appeal to a broad spectrum of elementary students; just prepare to watch and be amazed.

TRULY MAGICAL NATURE

Kids and adults alike may fight over Illuminature: Discover Hidden Animals with Your Magic Three Color Lens. The Italian artistic duo known as Carnovsky (Silvia Quintanilla and Francesco Rugi) bring their RGB Project (red, green and blue) to the world of children’s books, providing a unique journey through 10 of the world’s habitats, from the Andes Mountains to the Ganges River Basin.

Something amazing happens when you view Carnovsky’s artwork through the provided viewing lens. See daytime animals through the red lens, plant life abounds with the green lens, and nocturnal and crepuscular animals appear through the blue lens. A total of 180 are hidden within, waiting to be discovered.

While observers are busy staring at the wonderful transformations on these oversize pages, they’ll be soaking in plenty of data as well. Rachel Williams’ well-organized text provides facts about each destination as well as the varieties of species seen on each page. Leaping lizards, don’t miss this book!

This article was originally published in the December 2016 issue of BookPage. Download the entire issue for the Kindle or Nook.

Mustafa by Marie-Louise Gay

Mustafa by Marie-Louise Gay Saffron Ice Cream by Rashin Kheiriyeh

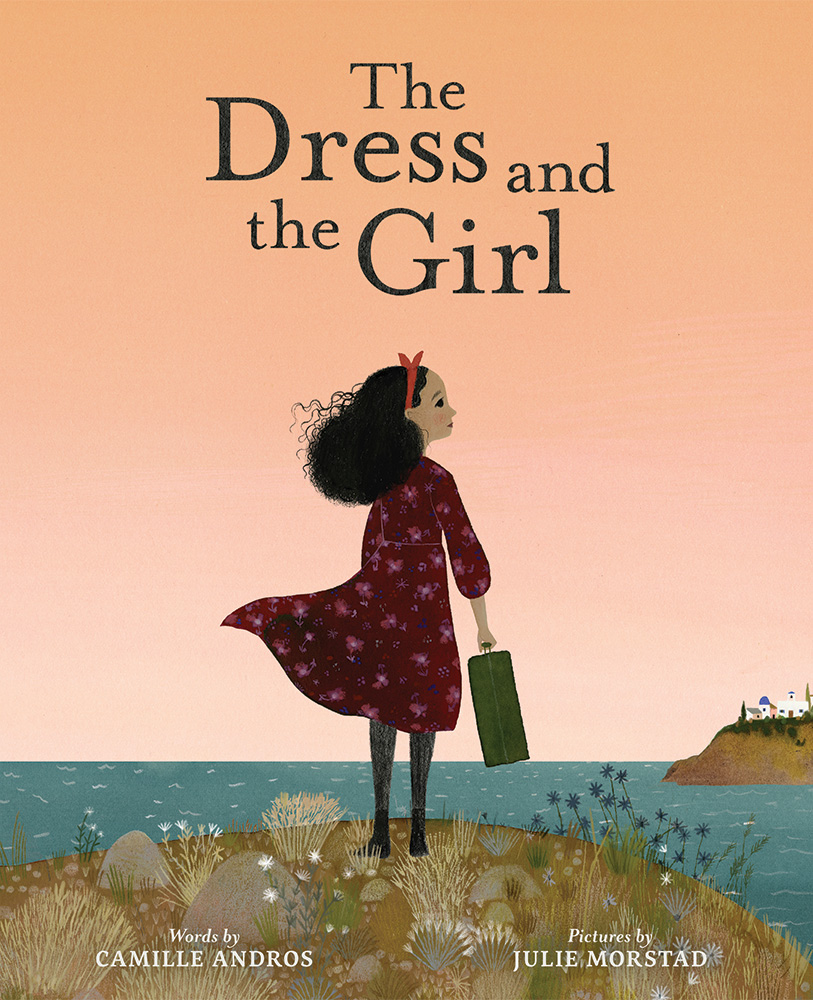

Saffron Ice Cream by Rashin Kheiriyeh The Dress and the Girl by Camille Andros, illustrated by Julie Morstad

The Dress and the Girl by Camille Andros, illustrated by Julie Morstad Ella and Monkey at Sea by Emilie Boon

Ella and Monkey at Sea by Emilie Boon Front Desk

Front Desk