Millers Kill is a picturesque small town in the Adirondack mountains of upstate New York. But as any mystery aficionado knows, even lovely leafy settings have a dark side—like two unsolved murders, one in 1952, the other in 1972. And then, in the present, Millers Kill Police Chief Russ van Alstyne learns it’s happened again. There is yet another murder with the same confounding characteristics: The victim is a beautiful young woman wearing a new dress, her purse and ID are missing and there are no bodily indications of what caused her untimely demise.

We talked to author Julia Spencer-Fleming about Hid From Our Eyes, her newest novel featuring Russ and his wife, Episcopalian priest Clare Fergusson, in which secrets from the past taint the future, politics and money loom large and the MKPD is racing to solve the crime before the police department is defunded and the killer gets away with it—again.

Congratulations on your new book! It’s been about nine years since your last Clare-and-Russ novel, Through the Evil Days. Did you revisit your previous books, delve into your notes, etc., to get yourself back into the mindset of your characters and their community?

I did all of those to reacquaint myself with Clare and Russ and the people of Millers Kill! One thing that helped a lot was relistening to the audiobooks with their wonderful narrator, Suzanne Toren. There’s something about listening rather than reading that allows me to experience the words in a fresh way, which in turn enables me to tune in to aspects of the characters that I might let my eye skip over if I was reading on paper.

In creating Millers Kill, you did such a wonderful job evoking the feeling of the Adirondacks, from the mountainous backdrop to the use of the word “camp” to refer to what’s often quite a large house. What is it about the area that made it feel like the ideal setting for your stories? Do you visit often as a refresher, or is the area vivid in your mind?

Although I’ve lived in Maine for 30 (mumble) years now, I’m originally from that part of New York, and having spent many of my growing-up years there, certain aspects are so deeply embedded I could probably write convincingly about the area even if I moved to Paris and never came back again! However, I do go back regularly to keep the sights and sounds and smells at the front of my brain. In addition to visiting, I try to keep a hand in with research and current events, so I’m not accidentally describing places as they were in 1979. Writing about Saratoga, for instance, requires me to update my memories, because the town has changed almost beyond recognition from when I was a girl.

I enjoy digging up the answers to questions and reading histories, so that part’s not hard, but the real pinch comes in knowing what you don’t know.

The goings-on in the book take place across decades, and while key aspects of police work (analyzing clues, following leads, conducting interviews) remain the same, medicine and technology have advanced in so many ways. Was it difficult to keep track of all of your characters while also remaining true to each era? Did you do lots of research about the specifics, perhaps with a police chief, medical examiner or the like on speed-dial?

I was fortunate enough to be able to call on a detective, a doctor and a pharmacist with specific questions for Hid From Our Eyes, and I did a lot of research into the details of life in the early 1950s and 1970s. I enjoy digging up the answers to questions and reading histories, so that part’s not hard, but the real pinch comes in knowing what you don’t know. I have friends like Rhys Bowen who exclusively write historical fiction, and I am in awe of their ability to nail the research and turn in books on time!

Tracking the changes of various characters as they grew older was much easier for me, in part because I tend to have fairly detailed biographies of major characters at the ready. So I knew a lot about Russ and his mother Margy, and about police chiefs Jack Liddle and Harry McNeil, who appeared in an earlier book in the series.

You went to college for art and acting, and you also have your J.D. Did you work as a lawyer before you became an author? What made you want to transition to the writing life? Do you think your studies in the arts and the law influence how and what you write?

I used to joke that law school taught me what NOT to write, but that’s not really fair. Despite centuries of jokes, good legal writing requires the “ABCs”—accuracy, brevity and clarity. Those aren’t bad habits for a novelist to pick up. Acting and theater, interestingly, have continued to prove useful, as the same techniques I learned for creating characters on stage are the ones I use for creating characters on the page. As for why I left the law to become a full-time writer? The money, obviously.

People interacting with them tended to stop at the uniform—a badge for him, a collar for her—and not see the real human underneath.

Both Russ and Clare are veterans who have experienced PTSD, and they’ve both chosen professions that require discretion and dignity. Do you think that’s a big part of what makes them work so well together as a couple and as parents?

The similarities of their professions are definitely what initially drew them together. People interacting with them tended to stop at the uniform—a badge for him, a collar for her—and not see the real human underneath. And, of course, they did see each other as fully human from the start.

One piece of writing has always been in my mind while writing these books: Leonard Cohen’s famous lyric, “There is a crack, a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in.” Russ and Clare are people who have been broken, they have broken each other, and cherishing their brokenness makes everything about them a little richer and more tender. I love the fact that they both clash with and complement each other. Without that, my novels would be shorter and a lot more dull.

Clare is an Episcopal priest, and your books’ titles are drawn from Episcopalian hymns. What does religion mean to you, in terms of your writing? Was it important to you to create characters who coexist lovingly, even if they have different views on faith?

One of the reasons the starting point for my series was Clare Fergusson was because I wanted to explore questions I had about my own faith. How do we act as believing people in a largely secular world? What does it mean to be the hands and feet of God? How, if you’re called on to love and forgive, do you love the unlovable and forgive the unforgivable? I also wanted to share my view of religion—that it’s OK to be scared, to doubt, to screw up—and, in a time when “Christian” increasingly is defined by narrow-mindedness and exclusion, to show people what my church is like: open minded, radically welcoming, progressive.

At the same time, it was also very important to me to make sure readers of any faith, or none, could connect with my characters. The last thing I wanted to do was preach. So there’s Russ, somewhere on the agnostic/atheist border, and Clare respects and honors his point of view. She doesn’t hide her beliefs, and she never tries to change his. You have Kevin Flynn, who’s probably a lapsed Catholic because he sleeps in on Sunday, and Hadley Knox, who goes to church because she thinks it’s good for her kids. In other words, I try to portray a picture of American religion as it’s actually experienced in a lot of Northern Kingdom/New England small towns.

Relationships between mentors and proteges figure prominently in Hid From Our Eyes. Russ mentors and supports his officers, Clare does the same for her new intern and police chiefs of the past offer wisdom and support to those next in line. Can you share your thoughts on the value of this sort of relationship?

Relationships between mentors and proteges figure prominently in Hid From Our Eyes. Russ mentors and supports his officers, Clare does the same for her new intern and police chiefs of the past offer wisdom and support to those next in line. Can you share your thoughts on the value of this sort of relationship?

It was something I started thinking about when raising my middle child, my son. I had never really seen a boy growing up before; my brother is nine years younger than I am and I was off to college well before his teen years. I came to realize, seeing my son and his friends, that while girls sort of fall into womanhood on their own, boys have to be taught to be men. They crave that relationship, from fathers or uncles or from mentors. The older and wiser person in the relationship has tremendous power, and I got to explore the use of that power for good and for ill in the book. And of course, there’s an echo of that idea in religion, in the idea of the initiate into sacred mysteries, which is where Clare comes in. All the while she feels she’s flailing around, doing “priesthood” wrong, she’s showing Joni and others, “This is what I do, you can do it too.”

Various characters in Hid From Our Eyes are struggling with difficulties from their past, like policewoman Hadley Knox, whose vindictive ex-husband is trying to cost her her job and custody of their kids, and Russ, who was a person of interest in the 1972 murder. Is this idea, how the past can have a hold on the present, something that intrigues you as you write your books ?

Oh, yes. “The past that won’t stay dead” appears again and again in my books. I used to say it came out of the context; small towns have long memories, and even after all the firsthand participants have passed, stories of memorable happenings and people continue to circulate. That’s still true, obviously, but now I also think it’s rooted in my own sense, as I get older, of just how much the past shapes each of us, and how hard it can be to move forward and break away from the events and individuals that have steered the course of our lives.

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our review of Hid From Our Eyes.

You kept your chapters short and your ending a cliffhanger, which definitely amps up the excitement and the page-turning! What’s your favorite kind of book to read? Do you enjoy mystery and suspense when you’re not the one creating it?

I love mysteries and thrillers—and cliffhangers!—and read a lot of it when, as you astutely put it, I’m not creating it. When I’m face down in a manuscript, it’s hard to delve into others’ mysteries; I find I either beat my breast in despair because my writing will never be as good as X’s, or the next day I write in some clever plot twist and then realize, oops! I just read that last night.

My other great love is science fiction. I’m actually a failed SF writer—my first attempt at a novel was a space opera. Terribly derivative and totally not what anyone was reading or selling back in the late ’90s. But the core of the plot was a murder on a space station, so my destiny was already apparent.

In the Bleak Midwinter, your first Russ-and-Clare book, was published in 2002. Has your approach to writing, and to your characters and their fictional world, changed since then? Do you think you’ll be writing about them for years to come?

I always thought the Millers Kill novels would be a five-book series, because the central story question was “Will they, or won’t they?” and how long can you stretch that out? Then I got to the point where I answered that question and discovered I had this large cast of layered, interesting characters to lay with, and wow, there were a LOT more stories I wanted to tell. Right now, I can see myself happy in Millers Kill for many more years.

My approach to writing since (ouch!) 2002? I’ve become a great deal more relaxed. I still plod through the middle of the book and agonize over wrapping up the ending and I’m always ping-ponging between complete conviction that I’m a hack or a genius, but I trust my process and choices much more than I did at the beginning. If I want to take a detour with a character or an event or a setting, I trust it will serve the greater story, even if it doesn’t feel like it at the time. And I have an excellent editor, who’ll make me take it out if I’m deluding myself!

Is there anything else you want to share about Hid From Our Eyes, or anything else you may have in the works?

I hope everyone will take a peek at it—you can’t pick it up in a bookstore and thumb through the pages, but there are excerpts at Macmillan.com and at my blog, JungleRedWriters.com. Meanwhile, I’m working on the 10th Clare and Russ book, working title: At Midnight Comes the Cry. I don’t want to make my readers wait another six years to resolve the current cliffhanger!

Author photo by Geoff Green.

You explore mental illness in empathetic and unflinching depth in your book—from Miranda’s and Kate’s perspectives as they suffer and attempt to find peace, as well as from the viewpoints of those who care about them and attempt to provide help. What was most valuable for you as you researched and created these characters?

You explore mental illness in empathetic and unflinching depth in your book—from Miranda’s and Kate’s perspectives as they suffer and attempt to find peace, as well as from the viewpoints of those who care about them and attempt to provide help. What was most valuable for you as you researched and created these characters?

You were born and raised in Atlanta, but now live on a horse farm in Southern Oregon. What is it about Atlanta that drew you back to setting Silence there, rather than closer to home in Oregon?

You were born and raised in Atlanta, but now live on a horse farm in Southern Oregon. What is it about Atlanta that drew you back to setting Silence there, rather than closer to home in Oregon?

For Sager, crafting the book-within-a-book was one of the most rewarding aspects of writing Home Before Dark. “It was really interesting to do the back-and-forth,” he says. “Maggie and her father were sort of in a dialogue with each other, almost comparing and contrasting their recollections with each other, like a fun-house mirror. . . . It was fascinating to come up with ways to do that, and have her father’s book be the unreliable narrator, in a sense.”

For Sager, crafting the book-within-a-book was one of the most rewarding aspects of writing Home Before Dark. “It was really interesting to do the back-and-forth,” he says. “Maggie and her father were sort of in a dialogue with each other, almost comparing and contrasting their recollections with each other, like a fun-house mirror. . . . It was fascinating to come up with ways to do that, and have her father’s book be the unreliable narrator, in a sense.”

High Place is almost a character in itself in this novel. Were you inspired by an actual house or location or was it purely a place in your imagination?

High Place is almost a character in itself in this novel. Were you inspired by an actual house or location or was it purely a place in your imagination?

There’s an obvious theme in the book about the pressures and expectations others put on a person, especially a star athlete like Dylan. His brother, Joel, is a gay man and faces his own prejudices. What compelled you to write about those pressures, and what lessons do you hope readers might take away from this novel?

There’s an obvious theme in the book about the pressures and expectations others put on a person, especially a star athlete like Dylan. His brother, Joel, is a gay man and faces his own prejudices. What compelled you to write about those pressures, and what lessons do you hope readers might take away from this novel?

Sydney finds her greatest ally in Theo, who candidly describes himself as a “mediocre white man.” Did you ever consider making Theo Black or multiracial? Or was he always white in your mind?

Sydney finds her greatest ally in Theo, who candidly describes himself as a “mediocre white man.” Did you ever consider making Theo Black or multiracial? Or was he always white in your mind?

Turton plotted his latest novel using a method he calls, appropriately enough, “lighthousing.” He explains: “I felt like I was my own little ship sailing in between these different lighthouses and trying to get my characters to safety at the end of the book. It sounds weird to say, but I almost left it up to them to find their way through.”

Turton plotted his latest novel using a method he calls, appropriately enough, “lighthousing.” He explains: “I felt like I was my own little ship sailing in between these different lighthouses and trying to get my characters to safety at the end of the book. It sounds weird to say, but I almost left it up to them to find their way through.”

How do you think your work in television has influenced and informed your work? For example, did your quiz-show experience give you confidence as you crafted characters who piece together clues and evidence? And do you think producing and directing aided you in managing big-picture aspects as well as fine details of your narrative? Were there any aspects of your story or characters or the writing process that you were uncertain about?

How do you think your work in television has influenced and informed your work? For example, did your quiz-show experience give you confidence as you crafted characters who piece together clues and evidence? And do you think producing and directing aided you in managing big-picture aspects as well as fine details of your narrative? Were there any aspects of your story or characters or the writing process that you were uncertain about?

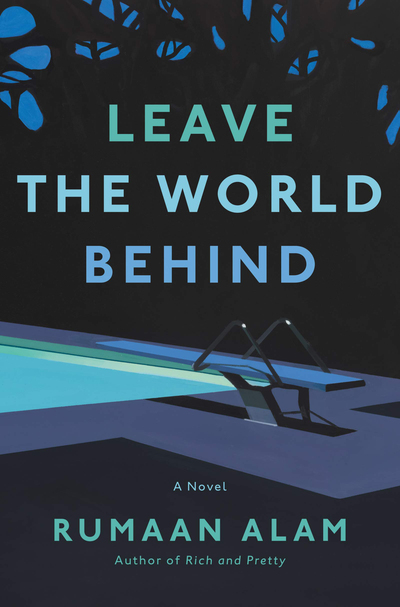

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Elements of this book felt very timely, including a fraught presidential election with possible Russian interference. Were you inspired by current events?

Elements of this book felt very timely, including a fraught presidential election with possible Russian interference. Were you inspired by current events?

Your approach to Emmy is so clever: an Instagram influencer who draws a million-plus followers by making her life seem worse, not better, than it is. Do you think people will reevaluate those they follow on social media, and why they follow them, after reading your book?

Your approach to Emmy is so clever: an Instagram influencer who draws a million-plus followers by making her life seem worse, not better, than it is. Do you think people will reevaluate those they follow on social media, and why they follow them, after reading your book?

Many of the characters in this mystery work in health care with, shall we say, mixed results. A character muses, “Sometimes working in health care felt like renovating a fixer-upper with modeling clay.” What about this often-Sisyphean pursuit appealed to you as a subject?

Many of the characters in this mystery work in health care with, shall we say, mixed results. A character muses, “Sometimes working in health care felt like renovating a fixer-upper with modeling clay.” What about this often-Sisyphean pursuit appealed to you as a subject?