Pull up a chair and dig into a four-course feast of picture books! These books offer innovative depictions of what it means to express gratitude, to share a meal and to be both welcoming and welcomed.

Thankful

“Every year when the first snow falls, we make thankful chains to last us through December,” explains the narrator of Thankful. She is stretched out on her bedroom floor, surrounded by a halo of colorful construction paper, hard at work transforming it into a paper chain. As she lists the things for which she is thankful, readers glimpse scenes of her life with her parents, new sibling and pet dog, at her school and with her friends.

Author Elaine Vickers’ text is wonderfully evocative. The girl’s list includes concrete and sensory observations, such as gratitude for “the spot under the covers where someone has just been sleeping” and “a cloth on my forehead when I feel sick.” In a humorous beach scene, the girl reflects that she is thankful “for wind and sand—but not at the same time.”

Readers will be entranced by Samantha Cotterill’s outstanding and unique art. To create her illustrations, Cotterill creates miniature 3D interiors, populates them with cutout characters, then photographs each diorama. She includes charming details, including real lights in various rooms and shining car headlights, along with construction paper chains so realistic in appearance that you’ll feel you could almost touch them. Colorful and original, Thankful will spark young readers to create their own thankful chains—and may inspire them to try their hand at making diorama art, too.

★ Let Me Fix You a Plate

The excitement of family gatherings is at the heart of Let Me Fix You a Plate: A Tale of Two Kitchens, inspired by author-illustrator Elizabeth Lilly’s annual childhood trips to see her grandparents. The book follows a girl, her two sisters and their parents as they pile into a car and drive first to West Virginia to their Mamaw and Papaw, then continue to Florida to visit their Abuela and Abuelo, before they finally return to their own home.

Lilly’s energetic illustrations capture these comings and goings, as well as the abundant details the narrator observes in her grandparents’ homes. At Mamaw and Papaw’s house, she sees a shelf of decorative plates and coffee mugs with tractors on them, eats sausage and toast with blackberry jam and helps make banana pudding. Abuela and Abuelo’s house is filled with aunts, uncles and cousins and the sounds of Spanish and salsa music. The girl picks oranges from a tree in the yard and helps make arepas.

Throughout, Lilly’s precise prose contributes to a strong sense of place. “Morning mountain fog wrinkles and rolls,” observes the girl on her first morning in West Virginia, while in Florida, “the hot sticky air hugs us close.” Lilly’s line drawings initially seem simple, almost sketchlike, but they expertly convey the actions and emotions of every character, whether it’s Mamaw bending down to offer her granddaughter a bite of breakfast or a roomful of aunts and uncles dancing while Abuelo plays guitar. Like a warm hug from a beloved family member, Let Me Fix You a Plate is a cozy squeeze that leaves you grinning and a little bit breathless.

Saturday at the Food Pantry

“Everybody needs help sometimes” is the message at the heart of Saturday at the Food Pantry, which depicts a girl named Molly’s first trip to a food pantry with her mom.

Molly and her mom have been eating chili for two weeks; when Molly’s mom opens the refrigerator, we see that it’s nearly empty. In bed that night, Molly’s stomach growls with hunger. Molly is excited to visit a food pantry for the first time, but she isn’t sure what to expect. As she and her mom wait in line, Molly is happy to see that Caitlin, a classmate, is also waiting with her grandmother. Molly greets her enthusiastically, but Caitlin ignores her. “I don’t want anyone to know Gran and I need help,” Caitlin explains later.

Molly’s cheerfulness saves the day, and the girls’ interactions contribute to a normalizing and destigmatizing representation of their experience. Molly asks her mom questions that reveal how the food pantry differs from a grocery store. Mom must check in before she begins shopping, for instance, and there are limits on how many items customers can have. “Take one bundle” reads a sign in the banana basket.

Author Diane O’Neil captures her characters’ trepidations head-on. Mom smiles “just a little, not like when they played at the park” at the volunteer who signs her in, and Molly is confused and sad when her mom tells her to put a box of cookies back because “the people in charge … want us to take sensible stuff.” Gradually, however, the occasion transforms into a positive experience for all.

Food insecurity can be a sensitive topic, and O’Neil—who went to a food pantry when she was a child—handles the issue in a reassuring, informative way. A helpful end note from the CEO of the Greater Chicago Food Depository explains that millions of people in the United States need help just like Molly and her mom, and provides readers resources to find it.

Illustrator Brizida Magro is a wizard of texture, whether depicting Molly’s wavy hair or the wonderful array of patterns in coats, sweaters and pants. Her ability to capture facial expressions and convey complex emotions is also noteworthy; it adds to the book’s emotional depth and makes the eventual smiles all the more impactful. The pantry shoppers’ diversity of skin tone, age and ability underscores how food insecurity can affect anyone. Saturday at the Food Pantry brims with sincerity and a helpful and hopeful spirit.

A Hundred Thousand Welcomes

“In one place or another, at one time or another, in one way or another, every single one of us will find ourselves in search of acceptance, help, protection, welcome,” writes Mary Lee Donovan in her introduction to A Hundred Thousand Welcomes, illustrated by Lian Cho.

With poetic text that reads like an invocation, the book is a fascinating around-the-world tour that explores the concept of welcome. On each page, a household from a different culture entertains guests. Many pages include the corresponding word for “welcome” in that culture’s language, including words and phrases in Indonesian, Arabic, Mandarin Chinese and Lakota Sioux. Back matter from Cho and Donovan explains the inspiration that sparked their collaboration and offers more information about the many languages spoken throughout the world and a detailed pronunciation guide to all of the words in the book.

Cho’s art is a multicultural feast of families and friends enjoying each other’s company. There’s a German chalet where kids play in the snow, a Bengali family greeting visitors who arrive in a small, colorful vehicle and more. The disparate scenes culminate in two shining spreads. In the first, people of all ages and nationalities share a meal at a table that’s so long, it can only fit on the page thanks to a breathtaking gatefold. In the next, an equally long line of kids sit atop a brick wall, chatting with each other and gazing up at a night sky full of stars as one child turns around and waves at the reader.

Although many picture books celebrate the fellowship of friendship and the love that flows during family gatherings, A Hundred Thousand Welcomes encourages readers to go one step further, to ready their own welcome mats and invite neighbors and strangers alike into their homes and hearts.

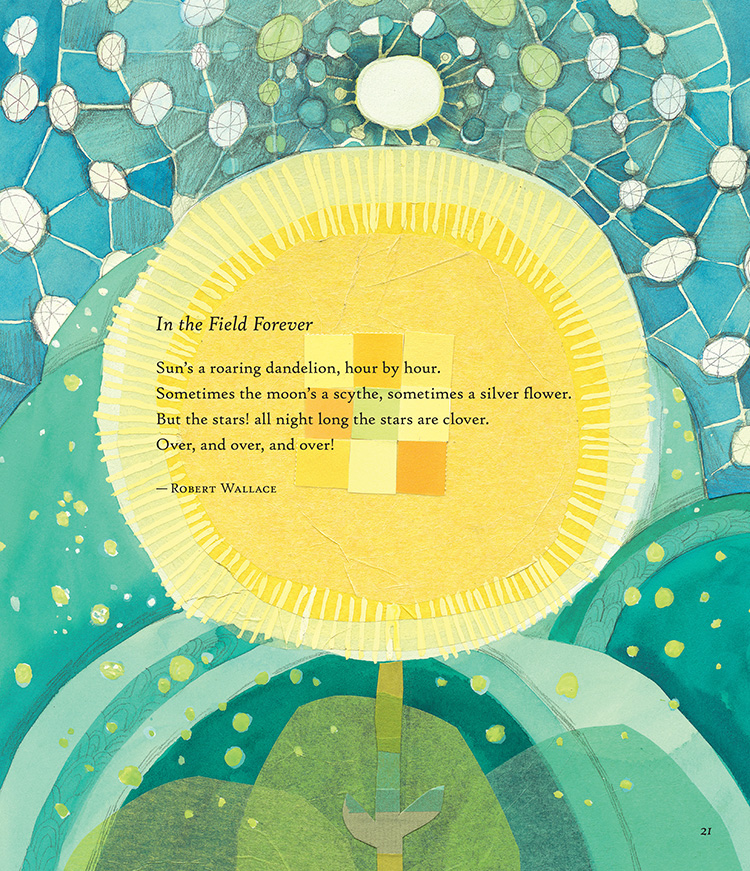

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Paul B. Janeczko, editor

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

Melissa Sweet, illustrator

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.

My entire childhood and adolescence was characterized by the inability to speak. Until I finally was given the tools to manipulate the hard contacts in my mouth when I was a senior in college, I was not able to speak a full sentence or communicate a full thought fluently—except to my animals.

Matthew Cordell, illustrator

Matthew Cordell, illustrator

Philip C. Stead, author

Philip C. Stead, author

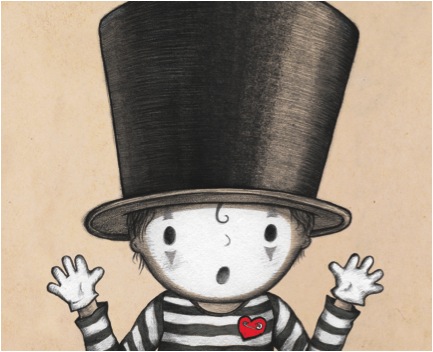

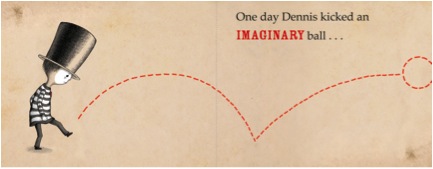

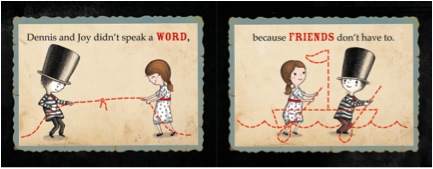

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled.

I was sitting in bed on a Sunday morning with a cup of coffee and a notebook, and I scribbled some notes for an idea about a character who only communicates through mime. This was an idea for a humorous illustrated chapter book, I thought. I’d never written anything laugh-out-loud funny, or a book with chapters. It was a stretch. But that morning, I felt like goofing off from house chores and escaped with writing. I’d already thought of the title before I came downstairs: The Silent Adventures of Mime Boy. I chuckled. On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.

On Monday, the character stayed with me. I started to think of a funny storyline for him. But I realized that this child, Mime Boy, would be teased in a school setting. And this broke my heart. There was nothing funny about it, and this wasn’t a chapter book I wanted to write. But the story had to be written.