David Ezra Stein sits poolside, hunched over his composition notebook and safely tucked in the shade of an umbrella. This is sunny California—ALA 2012 in Anaheim—and Stein, a lifelong New Yorker, is a little out of his element.

“This is so California,” he says, squinting at the hotel pool, which is empty except for a sunburned couple paddling around the far end. I can’t blame the guy for feeling out of place, especially with Disneyland around the corner. But it’s also clear that much of his inspiration and joy comes from his hometown streets of New York City, a fact particularly evident in his new picture book, Because Amelia Smiled.

The story opens on a panoramic spread of rainy NYC. It’s an explosion of smudgy colors and motion, and somewhere in the bustle, little Amelia smiles as she skips through the puddles. The butterfly effect is enormous. People’s lives change in England, Paris, Israel and beyond without even knowing it was all because of Amelia. The smile first brightens Mrs. Higgins’ day and encourages her to send cookies to her grandson in Mexico, who shares the cookies with his class and encourages one of his students to become a teacher, too—and so on and so forth, across oceans and continents. It comes full circle when Pigeon Man Jones releases his pigeons into the now-clear New York sky, causing Amelia to smile . . . and it all begins again.

The inspiration for Because Amelia Smiled came to Stein when he was a student at Parsons School of Design 13 years ago. It started with a conversation with his sister about Buddhism and how the choices you make affect those around you.

“Say somebody does something bad to you,” Stein explains, “like you’re trying to cross the street and they cut in front of you and won’t let you cross—which happens in New York all the time. So you can either carry that with you, carry that little scribbly cloud over your head for the rest of the day, or you could decide to go back to a few seconds before it happened, where you were just grooving along, having a good day, and then carry that energy forward instead of this grouchiness that affects everyone else you meet.”

A little girl's smile spreads happy vibes all around the world—from England to Israel—in the swirling new picture book from the author of 'Interrupting Chicken.'

After this conversation with his sister, Stein was walking home from the subway when Amelia’s story hit him. He wrote the whole tale on a paper bag, stopping every block or so to jot down the next effect of Amelia’s smile. The original version went on for more than 50 pages and visited India, Japan and New Zealand. (Fun fact: He still has the bag.)

Stein was taking a children’s book class at Parsons with author/illustrator Pat Cummings at the time, and he brought her the idea and presented it as “the interconnectedness of all beings.” He laughs at this: “I was in college at the time and I thought it was a really serious idea.” Cummings helped him pitch it to an editor, who was thrilled to publish him. However, Stein’s personal illustration style had yet to develop, and he stoutly refused to let them bring in another illustrator. He wanted to do it himself; he just wasn’t ready yet. So in 2000, Amelia was tucked away.

(In the middle of Amelia’s backstory, I slip off my sunglasses. Stein stops and looks at me as though I just sat down for the first time. “Oh, now I can see you,” he says with a smile, then goes back to his story.)

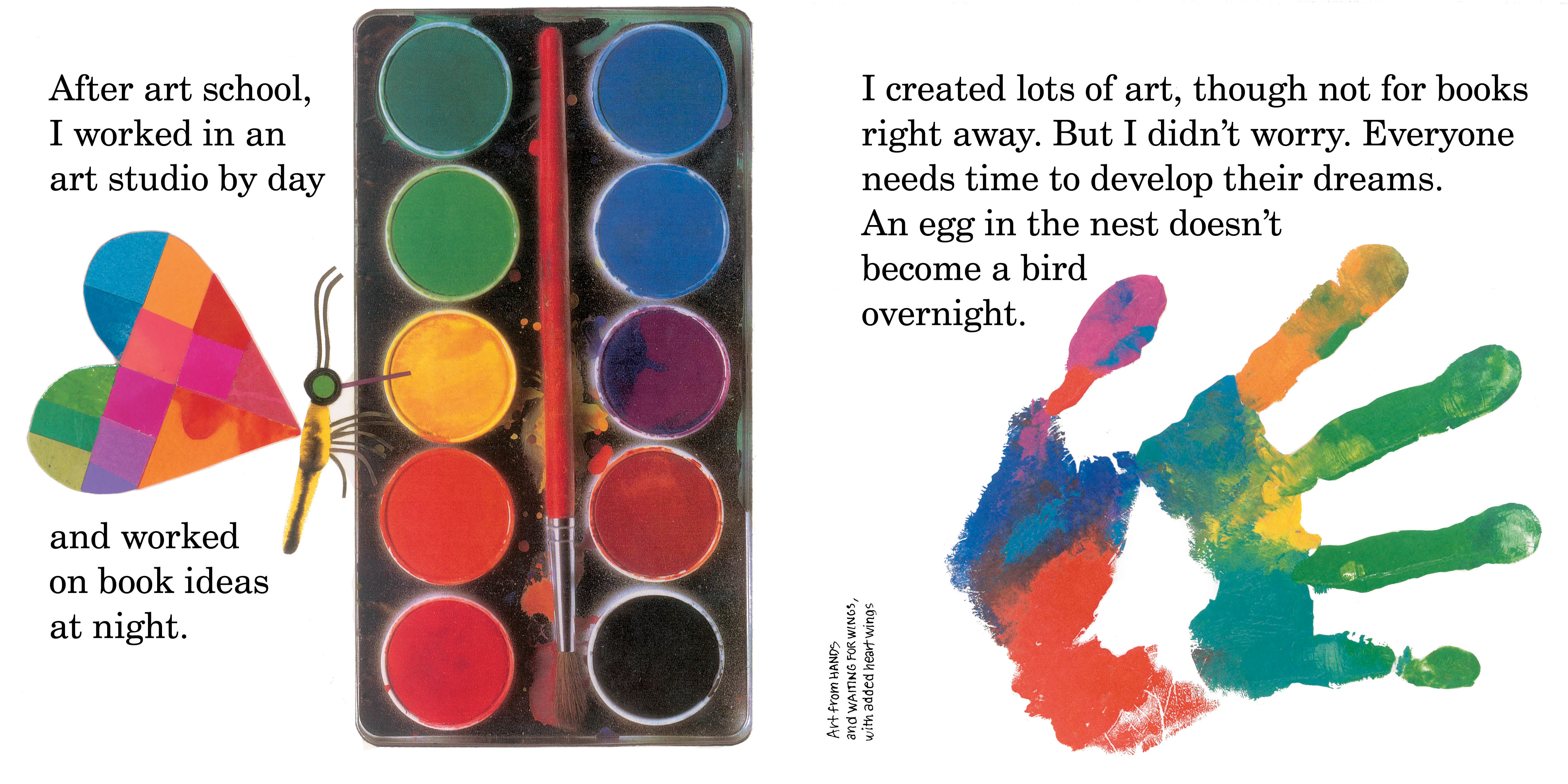

Stein spent the next few years sitting at his mother’s dining room table and drawing, drawing, drawing. He didn’t just make books; he also illustrated for set designers and interior designers.“I was doing watercolors and making really appealing renderings of spaces so the client would say, ‘Yes, let’s go ahead and make that,’” he says, his voice revealing how every artist feels about the work they have to do to pay the bills. However, those appealing watercolors came in handy and helped influence his first book with Simon & Schuster, Cowboy Ned & Andy (2006).

With several more picture books and a 2011 Caldecott Honor for Interrupting Chicken under his belt, Stein was ready to create the art for Amelia. He developed his own technique for the book, called “Stein-lining.” To imitate a printmaking look, he applied crayon to label paper, flipped it over and pressed on the back to create a line on the artwork. Most interestingly, he started each scene with “shapes of color.” Using crayon, he would draw the general shape of a yellow taxi or an orange building, then Stein-line over it to outline it. It’s almost like drawing from the inside out.

The effect creates illustrations filled with motion and swirling action, emulating the constant fluidity of day-to-day life. “There’s an immediacy,” Stein says. “Everyone’s moving; the cars are moving. Nothing stands still. The line work and the impressionistic quality of it—I’m trying to capture the energy and the momentum of the smile as it travels.”

Stein starts to flip through my copy of Amelia, and he smiles as though he’s looking through a yearbook. “I think of this book as a picture book novel,” he says, “because I really know all the characters. I did a lot of preparatory writing for each character to get into their voice and their world, and then I just threw it away and did a picture book.” I ask him if any of the characters will get their own story someday; he says yes, though the names will probably change.

Stein’s favorite characters are Gregor, the ex-clown in Paris, and his old flame, the Amazing Phyllis, who lives in Italy. Long story short, the effects of Amelia’s smile remind Gregor of Phyllis, and he sends her a bouquet with a note that reads, “Phyllis, after all these years, will you marry me?” The next page is arguably the best in the book: Red-lipped and silver-haired Phyllis tosses roses from a tightrope high above Positano, and people far below smile and point. “There’s something touching to me about that,” Stein says excitedly, thrilled to be sharing how much he loves these two old circus folk. “About people waiting till the last minute to declare their love and get married, but they still do it. They still have the joie de vivre.”

With Amelia tucked away for so many years, I ask if there are any other secret book ideas. Stein pulls out his composition notebook—his “famous author notebook,” he calls it—and flips open to a page covered with illustrations of dinosaurs eating one another’s heads, an unexpected preview of his next picture book with Candlewick. At first, it feels as though I’m trespassing on sacred ground, but Stein doesn’t seem to notice that he’s sharing something usually considered private. Much of the notebook is filled with handwritten scrawl, evidence of his hope to one day write a novel. “It’s like training for the marathon; you have to log a lot of miles of writing,” he says. It’s just one more thing for fans to look forward to.

Young readers will come away from Stein’s newest book with a sense of the powerful harmony of the world—and the knowledge that a smile wins over cloudy scribbles any day. I can’t be sure that our chat on a sunny Saturday in California changed the life of someone in Costa Rica or Croatia—but who’s to say it didn’t?