Do animals have a Santa Claus? This is just the sort of question Jan Brett would ask. In her new book, The Animals’ Santa, a young snowshoe hare in a cozy striped vest doesn’t believe all the other animals when they talk about Santa. As the squirrels and porcupines decorate the forest and share stories about the mysterious giver of gifts, the incredulous little rabbit crosses his paws. In the same way children wait up all night, hoping to hear to the sound of jingle bells and hooves on the roof, the little rabbit’s older brother—a true believer—decides to try to catch Santa. Brett’s classic illustrations capture the precious details and gentle beauty of the snowy wood, and children will treasure this tale of believing in Christmas.

What was the inspiration for this funny little story?

This funny little story just appeared to me all of sudden, the way you see in cartoons when someone has a light bulb idea over their head. . . . I was thinking, wait a minute, why don’t animals have a Santa Claus? I was thinking how I could make it into a poem about how the earth changes on its axis, and we go from fall into winter and about winter solstice. I was thinking, maybe in those couple of days, the animals don’t kill and eat each other. It was kind of poetic!

And I thought [the animals’ Santa] would be a snowy owl because they’re kind of like avian nomads, traveling all over from the arctic where they breed and where they live. They travel on silent wings, if you know about owls. What a perfect Santa Claus an owl would make!

The little skeptical rabbit’s brother decides to try to catch Santa in the act by hanging up pieces of ice. What was your inspiration for this?

I love this time of year when it’s cold enough for this ice to form. It has this kind of skin over the top of a puddle. It’s really fun to run through it and go crinch crinch crinch. It has very pretty designs, and often I’ll stop my run and see a little stream that’s coming through the woods, and it will be like lace. All this ice, this beautiful lacey ice. . . . There’s a tinkling noise that happens when it breaks. It could be a lovely trap, not a mean, awful trap.

What do you love most about these animals?

I love these animals from the arctic. I’ve always had an affinity—well, not an affinity so much as a curiosity about these animals that are white in the winter and brown in the summer. I mean, how did that ever happen? There’s something so sophisticated about how the pigment in the fur can change from winter to the summer. It sounds almost unbelievable.

One of my favorite elements of your illustrations has always been the border scenes. In The Animals’ Santa, little lemmings that look like elves make gifts for the woodland creatures. These scenes seem to be decorated with porcupine quills.

I had gone up to Canada, to Newfoundland . . . for a school visit. . . . We had stopped at this store that just specialized in native crafts. It’s a level of craft that’s really an art. I love these boxes made of porcupine quills, and I had collected them for years, not really knowing what they were. I just really love the tactile feeling of them and the colors that are used. Sometimes the Native Americans would use vegetation from native plants, so the colors aren’t knock-your-eye-out orange or red. They’re just these beautiful colors. So I met these people that have this beautiful art and found that some of these quills can be flattened out and form almost like a raincoat. . . .

One day in the summer I was driving along, and I saw a porcupine that had been hit. But it wasn’t squished, it just looked like it had went to sleep. So I went to the hardware store and got a big rubber mat that would go in a bathtub and gloves and a big, huge aluminum shovel to pick it up. The reason they’re called porky-pines is because they’re really heavy and fat! It took all my strength to get it into the car. . . . The quills, even if you just get near them and touch them, those barbs will stick you. They’re kind of dangerous. So I had these gloves and everything, and took picture of it, and this porcupine was kind of a major part of this book. . . . I started to photograph it . . . but then decided to do the next best thing, which is to draw it!

Do you have a favorite scene from The Animals’ Santa?

It would definitely be the owl. I really didn’t do it justice. This is a beautiful, beautiful animal. I’ve never really seen one—I might’ve only seen one on the wing one time but I didn’t have time to take a picture of it. They are so beautiful.

At the time I did the book, I had read somewhere that the white ones are mostly all male, so I made him all white. The females have these black markings on them—so beautiful. Last year there was an eruption of snowy owls. Apparently, from my reading, and also from this website by this guy Norman Smith, who’s from the Audubon and from my area in Boston, they had an eruption. What happens is, the lemmings and the snowshoe hares have a really good year, and there’s lots of vegetation for them to eat, and they can have multiple litters in a season. It quickly turns to fall, and then the owls feed on them, and all of a sudden you have more owls than the land can support. And who gets kicked out? The young males, so the big males can defend their territory and tend to stay up [in the arctic], and all these young males fly south. They came as far as Boston and even further, and they’d gravitate toward Logan Airport and to some of these barrier island beaches that look like the tundra. . . .

So that’s my favorite page, but I couldn’t really capture the luminescence of those feathers. It’s almost like a magical thing. It’s almost like the real animal is as unbelievable as the Santa Claus owl because of their lifestyle and the way they look. They almost kind of look like Santa Claus with their fluffy heads and mustache.

Your illustrations to me, and for so many readers, epitomize Christmas. As someone who’s constantly telling Christmas stories, how do you always find more inspiration in this season?

I would go back to what I would call my craft. I love to do details in my drawings. When I was 6 or 7, I knew I was going to be an illustrator. I used to promise myself that I’m not going to do simple drawings of cartoons, although I loved Charles Addams cartoons when I was that age. But I wanted to have things that really were pithy, that had a full range of emotions.

When you’re little, you have your own sense of aesthetics. You ask a 6-year-old what they’re going to wear to school, they’re going to tell you that they want this but not that. I think the smart parents respect that because it’s kind of a flag of a child’s individuality. It’s what they like and their idea of what beauty is. . . . I used to love books that felt like I could walk in the page and be in a different place, that transporting, that time-machine feeling of a really good story. Sometimes the illustration was the thing that propelled you in that world.

I always wanted to do that, but my style is so detailed that sometimes you don’t see the forest for the trees because it’s so busy. But the snow is the perfect foil for being able to show a little red squirrel with a brilliant coat and little whiskers that are kind of shining in the moonlight. The beauty of nature against the white. I think anybody who goes down a walk after a snow—it’s almost as if your whole color reference is booted, jump-started, because you’re seeing stuff for the first time. All of a sudden a birch tree, which is white, all of a sudden you can see the greens and the pinks and the yellows, and there’s always a few trees with a few leaves attached, even in a snowstorm. You wouldn’t see that if it was a late fall without any snow. I love that! It works for my pictures. The snow makes everything more defined.

When I go to my book signings, I talk about how everybody has their own style. Figuring out what makes your style work is part of the process. . . . One thing you need for that is time. That’s a big talking point when I talk to the children: Give yourself some time to draw and let your imagination take you away. It can be a human and exciting experience to, all of a sudden, create something.

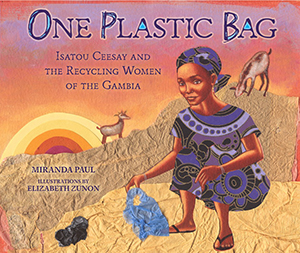

Paul is no stranger to the struggles in the West African nation. After earning English and secondary education degrees from St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the former teacher taught in Gambia more than a decade ago, where the seeds of inspiration for the book took root.

Paul is no stranger to the struggles in the West African nation. After earning English and secondary education degrees from St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the former teacher taught in Gambia more than a decade ago, where the seeds of inspiration for the book took root.