Tennessee author Jeff Zentner has written three beloved YA novels, including the 2017 William C. Morris Award-winning The Serpent King. His latest, In the Wild Light, is the story of Cash Pruitt, who is transplanted from his small opioid-ravaged Appalachian town to a fancy New England boarding school. There, he discovers the life-changing power of poetry. In this essay, Zentner explores how writing poems in Cash’s voice gave him the courage to finally incorporate poetry into his published fiction—and gave him a whole new literary hunger.

I’ve approached every book I’ve ever written with two questions in mind: What do I love? What do I fear? With my first book, The Serpent King, the answers were “friend groups of misfits in the rural South” and “publicly reckoning with faith,” respectively. For my second book, Goodbye Days, the answers were “the possibility of healing” and “grief.” For my third book, Rayne & Delilah’s Midnite Matinee, the answers were “people who try their best and come up short” and “writing from the perspective of two teenage girls when I’ve never even been one single teenage girl.”

And for my fourth book, In the Wild Light, the answers were “friends who go on an audacious and life-changing adventure together” and “putting actual poetry that I’ve written in a published book for everyone to see.” There’s a story behind the poetry part. One with many twists and turns.

I started reading poetry in high school, when I discovered Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks in an African American literature class. I fell, and I fell hard. My high school girlfriend and I would sneak onto the catwalks of a railroad bridge in our town and graffiti poetry on one of the columns. I often wrote my favorite Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks poems.

My love of Langston Hughes didn’t immediately lead me to try my own hand at poetry. Instead, it led me to music—the blues. I started listening to John Lee Hooker, Blind Willie Johnson and Lightnin’ Hopkins. I became obsessed. I bought a guitar and taught myself how to play by listening to cassettes and playing along, over and over, until the tape broke.

I wanted to write poetry. The idea of writing poetry for public consumption without having a guitar to hide behind terrified me.

I became ever more consumed with the pursuit of guitar technique. If you’ve ever listened to the musicians I just mentioned, you know that to play what they play takes a lot of practice. Like a brood of cicadas, poetry burrowed into my heart and went dormant, waiting for its time to reawaken.

I moved to Nashville, started playing shows as a solo act, formed a band and started recording and touring. My band played frequently in Bowling Green, Kentucky, due to its proximity to Nashville and its fanatical crowds of music lovers who would turn out for shows. After one of our gigs, a buddy of mine named Jonathan Treadway, who is a talented poet, painter and musician, asked me if I’d ever heard of Joe Bolton, the Kentucky poet. I hadn’t. He showed me some of Bolton’s poems. Reading them felt like watching a lightning storm. I went home that night and, at 3 a.m., ordered myself a copy of Bolton’s only poetry collection, The Last Nostalgia.

This is when poetry awoke from its long sleep and flowered in my heart again. Until that point, my musical career had almost exclusively consisted of performing interpretations of old Delta blues, northern Mississippi Hill Country and Appalachian old-timey songs. They came with their own sometimes centuries-old lyrics, and I never had to do any lyrical heavy lifting.

Joe Bolton changed that. A familiar hunger began gnawing at me. It was the same hunger that first compelled me to pick up a guitar to wrest songs from wood and wire. This time, I was being drawn to summon words from the ether. I began writing songs with my own lyrics, which eased my hunger. I made a goal to record an album of all-original songs. I did it. Then I recorded two more.

Joe Bolton changed that. A familiar hunger began gnawing at me. It was the same hunger that first compelled me to pick up a guitar to wrest songs from wood and wire. This time, I was being drawn to summon words from the ether. I began writing songs with my own lyrics, which eased my hunger. I made a goal to record an album of all-original songs. I did it. Then I recorded two more.

And for a while, it kept the hunger at bay.

But all of these things I’m talking about take time, and one day I looked up and I was 35 years old. That may not sound old, but in undiscovered musician years, it might as well be 130. Musicians seldom make it big after age 30. I had reached the end of my professional road in music, with little hope of ever reaching much of a wider audience. I started volunteering at Tennessee Teen Rock Camp and Southern Girls Rock Camp, summer camps where teenagers learn how to be rock musicians. I figured, hey, if the bonfire of a dream of making a living in music has burned down to embers for me, maybe I can pass the spark on to someone who can build it back into a bright flame.

Working with these young adults, I fell in love with a very specific thing about them—the way they loved the art they loved. The way they let the art they loved move them and shape them reminded me of my own young adulthood. They created themselves in its image. The hunger I had managed to suppress for a while roared back. I wanted to make art for young adults. I was too old to make the kind of music that would reach them. So I decided to change horses completely and move to an artistic world where age is less of a limiting factor: book publishing. People regularly publish their first books well into their 40s, 50s and even 60s.

Writing YA novels felt pretty good and suppressed the hunger for a while. But a new hunger soon nagged at me. I wanted to write poetry. The idea of writing poetry for public consumption without having a guitar to hide behind terrified me. Then a thought occurred to me. What if I wrote poetry without writing poetry? What if I insulated myself by putting the pen in the hand of one of my characters and letting him write the poetry?

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our review of In the Wild Light.

I came up with an idea for a story that would be Dead Poets Society meets Looking for Alaska—two best friends from Appalachia who end up attending an elite Connecticut boarding school, where one of them enrolls in a poetry class. That book, In the Wild Light, contains poems written by the character named Cash Pruitt. Cash Pruitt is, of course, me. It took almost 15 years, but I finally got up the courage to write poetry.

I have a new hunger now, to write and publish a book of poems without hiding behind a guitar or any of my characters—without tricking my publisher into making me a published poet.

I think that day will come. When it does, it will have come at the end of a great journey. I’ll be hungry until it does. I hope when I do it, it satisfies the hunger for a while.

But then I hope I get hungry again.

Author photo of Jeff Zentner courtesy of Annie Clark.

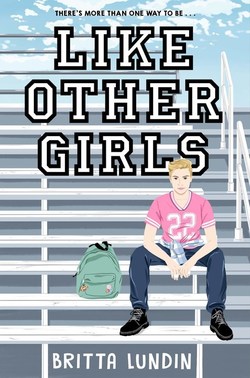

Well. She’s spent years acting like just another one of the guys, so as Mara begins to actually excel on the gridiron, she’s surprised when her teammates’ sexism turns on her with full, resentful force. Even worse, four volleyball girls—including Mara’s frenemy, Carly, and crush, Valentina—join the team. Suddenly Mara’s a role model whether she likes it or not. (Reader, she does not.)

Well. She’s spent years acting like just another one of the guys, so as Mara begins to actually excel on the gridiron, she’s surprised when her teammates’ sexism turns on her with full, resentful force. Even worse, four volleyball girls—including Mara’s frenemy, Carly, and crush, Valentina—join the team. Suddenly Mara’s a role model whether she likes it or not. (Reader, she does not.)  In Dangerous Play, debut author Emma Kress demonstrates with devastating realism just how quickly things can change. When Zoe is sexually assaulted at a party, her optimism and confidence are crushed under the weight of PTSD, and her bright “fockey”-filled future now seems impossibly far away.

In Dangerous Play, debut author Emma Kress demonstrates with devastating realism just how quickly things can change. When Zoe is sexually assaulted at a party, her optimism and confidence are crushed under the weight of PTSD, and her bright “fockey”-filled future now seems impossibly far away.

Edie in Between

Edie in Between The Witch Haven

The Witch Haven Bad Witch Burning

Bad Witch Burning