The publication of a book as extraordinary as Daniel Nayeri's Everything Sad Is Untrue would be a momentous occasion all on its own. Based on Nayeri's childhood experience of fleeing religious persecution in Iran to eventually settle in Oklahoma, BookPage reviewer Luis G. Rendon says Nayeri's "patchwork story forms a stunning quilt, each piece lovingly stitched together to create a saga that deserves to be savored."

Everything Sad Is Untrue is also the first book to be published by a brand-new independent children's publisher, Levine Querido. Founded by Arthur A. Levine, who helmed an eponymous imprint at Scholastic and also held the role of editor in chief at Knopf Books for Young Readers, Levine Querido launches its inaugural list in the fall of 2020.

Nayeri and Levine give BookPage readers a behind-the-scenes glimpse at what it takes to write and edit a middle grade novel, bring us up to speed on the story of Levine Querido thus far and share their hopes for their work.

An editor’s work is often invisible to a reader, but most writers are quick to acknowledge what a good editor can bring to a book. (To borrow a turn of phrase from Khosrou, the narrator of Daniel's book, perhaps a good editor is like a god who speaks and a god who listens.) Because you’ve both worked as editors within the children’s book industry and both have written children’s books yourselves, I’d love to hear about the work you did together to shape Everything Sad Is Untrue. What questions did you ask each other and yourselves as you worked on the book?

Levine: I would strongly resist the characterization of the editor as a kind of G-d! At least in the traditional sense of an all-knowing, all-seeing, omnipotent being who shapes, controls and forms the book, with the author as clay. If you could meet Daniel, you'd laugh hard at the notion of me (or anyone) assuming that role with him!

Levine: I would strongly resist the characterization of the editor as a kind of G-d! At least in the traditional sense of an all-knowing, all-seeing, omnipotent being who shapes, controls and forms the book, with the author as clay. If you could meet Daniel, you'd laugh hard at the notion of me (or anyone) assuming that role with him!

And that's not how I think of the job anyway; I think of myself as the smart best friend who loves you and reads your manuscript because he already thinks you're amazing and just wants to give you a few helpful reactions and impressions. If anything, for me G-d is that ineffable burst of wonder that happens when creative people come together with pure trust. I don't know—Daniel, was G-d part of it for you at any part of the process of this book?

Nayeri: I like this. We’re going straight into religious conversation on question one. Leave it to you, Arthur, to get to the heart of the matter immediately. I have often heard from my fellow editors that the last taboo of children’s literature is religion. But this is a book about religion entirely. It is the reason the younger narrator is a refugee. Religion is the dividing line between his mother and father. And underneath his obsession with counting the memories of his grandfather is the anxiety that when they both die, they will go to different places. For me, G-d was in every word, or at least I hope so.

Nayeri: I like this. We’re going straight into religious conversation on question one. Leave it to you, Arthur, to get to the heart of the matter immediately. I have often heard from my fellow editors that the last taboo of children’s literature is religion. But this is a book about religion entirely. It is the reason the younger narrator is a refugee. Religion is the dividing line between his mother and father. And underneath his obsession with counting the memories of his grandfather is the anxiety that when they both die, they will go to different places. For me, G-d was in every word, or at least I hope so.

But to return to your description of the author/editor relationship, I agree. I think the best version of that relationship is one where each person thinks the other is a master at their work. When I read an editorial note, I am naturally resistant. It hurts in the way that physical therapy hurts. An immediate reaction would be to argue, dismiss or distract from the points being made. But somewhere deep down, I know my editor is brilliant. He isn’t saying this to be obtuse. And my child mind has to relent to guidance. But then, maybe I was a recalcitrant child. Were there any instances you felt I never quite managed to hear you out?

Levine: Ha! We're both author-editors so I know exactly what you mean. I could sometimes feel you struggling to consider my reactions; we had some excellent back and forth about the bull-killing scene, remember? But it's a good example of the process working on both sides. I shared my visceral reaction to some details and placement decisions, but I also felt total confidence that your vision for the book in its entirety REQUIRED many of those details as part of an accumulation of imagery and metaphor—meaning, ultimately, I might tell you that I recoiled at something, but if you said, "Good! I wanted the reader to recoil!" then I was happy.

Levine: Ha! We're both author-editors so I know exactly what you mean. I could sometimes feel you struggling to consider my reactions; we had some excellent back and forth about the bull-killing scene, remember? But it's a good example of the process working on both sides. I shared my visceral reaction to some details and placement decisions, but I also felt total confidence that your vision for the book in its entirety REQUIRED many of those details as part of an accumulation of imagery and metaphor—meaning, ultimately, I might tell you that I recoiled at something, but if you said, "Good! I wanted the reader to recoil!" then I was happy.

I have a great deal of faith in the capacity of young people to experience a huge range of emotion and experience through literature; I think that from time immemorial that has been the magic power of storytelling.

I don't want "obedience" in an author. I want someone who is so thoughtful and aware of his own work that he can be the ultimate arbiter of decisions (meta and micro) about the writing. As long as he thinks my reactions are sympathetic and intelligent then I hope he can give them the room to be helpful. And I'm very confident that you did that, Daniel. Was there ever a time you thought I strayed from that and was a bossy boss?

Nayeri: That’s a great point. One aspect of your editorial approach was to inhabit the reader and offer the most transparent play-by-play reactions to the sentences. Of course, I would wince whenever you’d write that a description of digging out a septic tank almost made you vomit. But then, as you said, I would consider that a victory. That’s how digging out the septic tank should feel, after all.

Nayeri: That’s a great point. One aspect of your editorial approach was to inhabit the reader and offer the most transparent play-by-play reactions to the sentences. Of course, I would wince whenever you’d write that a description of digging out a septic tank almost made you vomit. But then, as you said, I would consider that a victory. That’s how digging out the septic tank should feel, after all.

I think the only time you insisted on something was around the opening line. The book began “My first memory is blood, slopping from the throat of a terrified bull, and my grandfather …” and you were adamant that many readers would recoil if I started there, before introducing the narrator himself. I whined. I squirmed. I fought. I pouted. But finally, you got me to “just try” a different opening. I did so begrudgingly, and now I admit, you were right. The new opening is far stronger. I love that Khosrou’s sense of humor is offered up first. And I snuck in his reaction to your note, which is an apology for the blood, and an insistence that it’s important. You were the reader he is addressing in that section, Arthur. And you were right. I’ll say it again. The first opening was for me. The second opening was for the reader.

So much of what makes a masterful editor is invisible to authors. Their job is to be wind on a river. They nudge the flow of events so gently, with such patience, that the river itself doesn’t realize it is being directed.

Another moment that Khosrou speaks to you, Arthur, is when he says, “You might be thinking, what kind of twelve-year-old talks like that?” Do you remember? That was your note. And Khosrou answered you back, “The kind of twelve-year-old that speaks three languages.” We talked a lot about sophistication of language versus sophistication of thought and how readers would take to both. Where do you land on that? When telling a story to a younger audience that includes painful experiences, how do you edit to give them insight without burden?

Levine: I guess the first part of that answer is that I have a great deal of faith in the capacity of young people to experience a huge range of emotion and experience through literature; I think that from time immemorial that has been the magic power of storytelling. And this turns out to be both an explicit and implicit theme of your book, Daniel. I’m more afraid of depriving young people of the means to see aspects of their own experience reflected, or the opportunity to develop empathy, than I am of burdening them.

Levine: I guess the first part of that answer is that I have a great deal of faith in the capacity of young people to experience a huge range of emotion and experience through literature; I think that from time immemorial that has been the magic power of storytelling. And this turns out to be both an explicit and implicit theme of your book, Daniel. I’m more afraid of depriving young people of the means to see aspects of their own experience reflected, or the opportunity to develop empathy, than I am of burdening them.

In the context of the book itself, I felt that as long as you stayed rigorously true to Khosrou’s actual emotion-within-the-story (and you most certainly did!) that you would never go beyond the emotional capacity of the reader. I also think it’s (always) important to ask oneself who the “reader” is we’re talking about? (As in, “for what age reader is this book for?”) Which reader? Are we talking about 11-year-old Arthur, whose mother and aunt taught him to read before kindergarten, or a reader like my son who only became confident with reading now, in his mid-teens.

The concept of the generic reader is a dangerous one—it leads to unexamined racism, for instance, and unnecessary “dumbing down.” For those readers with confidence and the connection of close experience, the narrative is its own path. For those for whom the experience is further from theirs, I think they only need periodic bridges to help them stay on that path—and small moments such as those you cite above (Khosrou talking to the reader disguised as me) are examples of those bridges.

I also think that while you never shied away from the painful experiences, as you put it, you also were generous with a laugh, quick to offer the reader a mouth-watering cream puff (literally) and unembarrassed by love and joy.

Are you satisfied with the balance? Did you wind up leaving anything out because you felt it would be too “tough” for the reader? It’s hard to imagine. For all that I’ve said here, you know I’m not very “tough” myself, so I would have flagged any sensitive reaction I had, but I don’t think I would, in retrospect, have asked you to consider removing anything that remains.

Nayeri: I think we agree. To me, any work that doesn’t prioritize revealing the truth—even narrowly confined to a particular moment or theme—is a project I would avoid. But as you pointed out, the middle grade category has what I would consider to be the widest range in audience. In some countries, Everything Sad Is Untrue will be published for adults. In this one, it may be read by precocious 10-year-olds. I think this is because middle grade novels are often coming-of-age novels. They are the threshold into adulthood. And we all come to that threshold at different times. I suppose what I mean is simply that the novel must express the truth of that transition into the realm of the adult. And that transition is usually a bloody one.

Nayeri: I think we agree. To me, any work that doesn’t prioritize revealing the truth—even narrowly confined to a particular moment or theme—is a project I would avoid. But as you pointed out, the middle grade category has what I would consider to be the widest range in audience. In some countries, Everything Sad Is Untrue will be published for adults. In this one, it may be read by precocious 10-year-olds. I think this is because middle grade novels are often coming-of-age novels. They are the threshold into adulthood. And we all come to that threshold at different times. I suppose what I mean is simply that the novel must express the truth of that transition into the realm of the adult. And that transition is usually a bloody one.

I am an inveterate lover of overlong titles, so for a while I wanted If You Don’t Stop You’re Unstoppable. I liked the hopefulness of that last one, the idea that this isn’t just a tale of immigrant woe. But it also sounds like those ’90s-era sports equipment ads that ended, “No Fear!”

But is there material I would share with an adult that I would withhold from a 10-year-old? Of course. I’ve known sensitive 10-year-olds with their own traumas to endure, who needed a few more years of gentleness and psychological assurance. And I’ve known plenty of 12-year-olds who need to be smacked out of their constant self-regard. It takes a parent, librarian or teacher to make that distinction, to put the right book in their hands and to speak with them afterward about what just happened. That’s the highest purpose of a “gatekeeper,” in my opinion.

That was also one of the main uses of addressing the reader in the book. Khosrou is choosing to share his pain and suffering with young readers, but also talking them through it manageably. I think that’s what the title refers to as well.

Arthur, introduce us to Levine Querido. What will make Levine Querido’s books unique?

Levine: Our motto is “Beloved books, beautifully made,” so I hope readers will find that the contents of the books are as extraordinary and surprising as the way they look and feel. We hope to be passionate advocates for authors and illustrators who come from previously underrepresented groups, in English and in translation, and to shine a spotlight on their talents.

Levine: Our motto is “Beloved books, beautifully made,” so I hope readers will find that the contents of the books are as extraordinary and surprising as the way they look and feel. We hope to be passionate advocates for authors and illustrators who come from previously underrepresented groups, in English and in translation, and to shine a spotlight on their talents.

We are choosing books to publish because we truly think they are incredible, choosing artists because we think their art is gorgeous.

Daniel, as you mention in your book’s acknowledgements, Arthur is a mythical figure in children’s publishing. Can you talk a bit about the myth of the man? What did he and the team at Levine Querido bring to this book?

Nayeri: So much of what makes a masterful editor is invisible to authors. Their job is to be wind on a river. They nudge the flow of events so gently, with such patience, that the river itself doesn’t realize it is being directed. They find like-minded librarians and booksellers and throw themselves into the actual work of community-building. They literally spend all day in the grind house of managing outsized egos, constant misunderstandings or internecine corporate warfare, and they spend nights gently coaxing a manuscript into the world. And at end, they’re judged on their list.

Nayeri: So much of what makes a masterful editor is invisible to authors. Their job is to be wind on a river. They nudge the flow of events so gently, with such patience, that the river itself doesn’t realize it is being directed. They find like-minded librarians and booksellers and throw themselves into the actual work of community-building. They literally spend all day in the grind house of managing outsized egos, constant misunderstandings or internecine corporate warfare, and they spend nights gently coaxing a manuscript into the world. And at end, they’re judged on their list.

All that, and I haven’t even addressed what LQ has managed to do as a new publishing company. To put the likes of Antonio Cerna and Caroline Sun in decision-making seats—these are two people I’ve admired for more than a decade. Nick Thomas is so clearly a virtuosic editor. There’s Alexandra Hernandez, the team at Chronicle . . . I could go on. I’m tempted to just start listing names, as if I’ve won something. The reality is that I feel I’ve finally won the attention and effort of these sorts of people. I couldn’t begin to explain what that means to someone like me.

Arthur, how did Everything Sad Is Untrue first come to you? What made it stand out to you? How far into reading did you get before you knew you wanted to publish it?

Levine: I had met the intimidatingly smart and charming Mr. Nayeri at an American Library Association conference one year and we struck up a friendship and mutual admiration society. Jo Volpe, his incredible agent, sent me the manuscript, which left me gobsmacked. The fluidity with which Daniel went from the funny earthy realities of middle school life to the exquisite poetry of stories with a thousand-year history . . . only a very, very gifted author can do that.

Levine: I had met the intimidatingly smart and charming Mr. Nayeri at an American Library Association conference one year and we struck up a friendship and mutual admiration society. Jo Volpe, his incredible agent, sent me the manuscript, which left me gobsmacked. The fluidity with which Daniel went from the funny earthy realities of middle school life to the exquisite poetry of stories with a thousand-year history . . . only a very, very gifted author can do that.

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our starred review of Everything Sad Is Untrue.

Daniel, your acknowledgements and author’s note provide a glimpse into the genesis of this book. It took you 13 years to write, and you mention that it was your friend Stacey Barney, the executive editor at Putnam, who suggested you try writing it from the perspective of your younger self. What did adapting that new perspective change for you?

Nayeri: As an adult, I’ve had the opportunity to process a lot of the raw, chaotic elements of my childhood. And that was how a lot of the early drafts read. They were distant from the pain, almost anthropological. By going back and telling the story as I would have as a kid, the reader can see he’s still in the midst of it. He is practically shaking as he describes a moment when he has had his thumb pulled out of its socket by an older kid. He doesn’t want you to think he was afraid. He insists that he didn’t cry, though we know he did. The unreliable and yet emotionally transparent narrator was the best part of shifting the story to my younger self.

Nayeri: As an adult, I’ve had the opportunity to process a lot of the raw, chaotic elements of my childhood. And that was how a lot of the early drafts read. They were distant from the pain, almost anthropological. By going back and telling the story as I would have as a kid, the reader can see he’s still in the midst of it. He is practically shaking as he describes a moment when he has had his thumb pulled out of its socket by an older kid. He doesn’t want you to think he was afraid. He insists that he didn’t cry, though we know he did. The unreliable and yet emotionally transparent narrator was the best part of shifting the story to my younger self.

Tell us about your mom, to whom you’ve dedicated the book. Introduce her to readers who haven’t read your book yet and don’t know why I’m asking this question. Did writing the book change your relationship with her? Has she read the book?

Nayeri: My mother is the central figure of the story. In the book she is described as not much taller than a potted plant and yet the strongest person I’ve ever met. When I was young, she converted to Christianity, which is a capital crime in our home country of Iran, so we had to escape. My father chose to stay. My mother, sister and I became refugees and finally found asylum in Edmond, Oklahoma. Those are the basic facts. The reality is that we watched this incredibly complicated idea, that someone’s religious convictions would lead her from a fairly well-to-do family across the planet into a life of precarity. As kids, there was a constant attempt to understand the “why” of it all.

Nayeri: My mother is the central figure of the story. In the book she is described as not much taller than a potted plant and yet the strongest person I’ve ever met. When I was young, she converted to Christianity, which is a capital crime in our home country of Iran, so we had to escape. My father chose to stay. My mother, sister and I became refugees and finally found asylum in Edmond, Oklahoma. Those are the basic facts. The reality is that we watched this incredibly complicated idea, that someone’s religious convictions would lead her from a fairly well-to-do family across the planet into a life of precarity. As kids, there was a constant attempt to understand the “why” of it all.

There are a lot of people who speak for refugees, but not a lot of people who listen to them. I would love nothing more than to have young readers hear that term and think of Khosrou, someone they met in the course of reading the book, someone they may have come to like.

I don’t think the book changed our relationship much. I suppose I gained even more respect for what she endured. She has always known I wanted to write the book—ever since I was 10 years old—so it was mostly a feeling of relief after it was done. When she read the book, she disagreed with my read on several characters. For instance, she has a much kinder view of her father than I do. Admittedly, she knew him far better than I did. We talked about it. I even mentioned it in the author’s note. But at end, the book was from my perspective as a preteen.

Did Everything Sad Is Untrue ever have other titles that you’d be willing to share? When and how did its current title emerge?

Nayeri: Well, I thought about calling it Refugee, but that was taken. The adult version was titled The Persian Flaw, but that makes it sound like some sort of polemic about modern politics. And I am an inveterate lover of overlong titles, so for a while I wanted If You Don’t Stop You’re Unstoppable. I liked the hopefulness of that last one, the idea that this isn’t just a tale of immigrant woe. But it also sounds like those ’90s-era sports equipment ads that ended, “No Fear!”

Nayeri: Well, I thought about calling it Refugee, but that was taken. The adult version was titled The Persian Flaw, but that makes it sound like some sort of polemic about modern politics. And I am an inveterate lover of overlong titles, so for a while I wanted If You Don’t Stop You’re Unstoppable. I liked the hopefulness of that last one, the idea that this isn’t just a tale of immigrant woe. But it also sounds like those ’90s-era sports equipment ads that ended, “No Fear!”

What I really wanted was a title that didn’t deny fear or pain, but rather looked past it. That was how I got to the passage in the Lord of the Rings when Samwise Gamgee sees Gandalf return from the dead, and asks, “Will everything sad become untrue?” I adore Sam’s childlike faith there. If Gandalf had said so, Sam would believe that everything was about to become as it ought to be. I loved that, so the title was Everything Sad Will Become Untrue for nearly the entire time I wrote the last draft.

As I wrote, I began to consider that future-tense verb, Will Become. I wanted to add a bit of our narrator, Khosrou, to the sentiment. He, too, is as desirous as Samwise for a world that ought to be, but he’s also a bit more confident—or at least he presents himself that way. He would be the kind of kid who asserts the future as the present. Everything sad IS untrue. He’s jumping the gun. He wants his current pain to be redeemed by a better future. It’s technically a lie. Everything sad is NOT untrue. Not yet. And so that became the final title.

Arthur, I’m not sure whether the letter you wrote to accompany advance review copies of the book will end up in the finished book that readers will buy and borrow from their libraries, so I want to give you the opportunity now to get up on a proverbial soapbox and tell anyone reading this: What do you love about Everything Sad Is Untrue?

Levine: I think I could answer that question from a different angle every hour of the day. It could be the mouthwatering descriptions of food. It could be the descriptions of place so vivid you can feel the wind of an Oklahoma hurricane or smell the jasmine in a garden in Isfahan. It could be the comfort of reading a story told by someone else who knows how hard it is to make a friend in a new place. It could be the shock of a sudden moment of violence in your own living room, or the even greater shock of who comes to your defense. It’s the sharp suspense of a flight for your life. It’s the wonder of a lyrical history that lives in one man’s memories. Ask me again in an hour!

Levine: I think I could answer that question from a different angle every hour of the day. It could be the mouthwatering descriptions of food. It could be the descriptions of place so vivid you can feel the wind of an Oklahoma hurricane or smell the jasmine in a garden in Isfahan. It could be the comfort of reading a story told by someone else who knows how hard it is to make a friend in a new place. It could be the shock of a sudden moment of violence in your own living room, or the even greater shock of who comes to your defense. It’s the sharp suspense of a flight for your life. It’s the wonder of a lyrical history that lives in one man’s memories. Ask me again in an hour!

As you’re answering these questions, the launch of your first season of books is right around the corner. How are you feeling? What’s been different for you about the process of working on these books? What have you discovered about running an independent publishing company versus working as an editor or running an imprint inside of a larger publishing corporation?

Levine: Well, in many ways the launch has been building for a year. I hired my incredible editors Nick Thomas and Megan Maria McCullough; we integrated with Chronicle, the best distributor anyone could ask for; and we’ve been working with Antonio Cerna and Alexandra Hernandez to create wonderful marketing and publicity plans, then scrapping them and doing them over again in the digital world. Now it’s like we’re putting on our party hats and waiting to throw the doors open!

Levine: Well, in many ways the launch has been building for a year. I hired my incredible editors Nick Thomas and Megan Maria McCullough; we integrated with Chronicle, the best distributor anyone could ask for; and we’ve been working with Antonio Cerna and Alexandra Hernandez to create wonderful marketing and publicity plans, then scrapping them and doing them over again in the digital world. Now it’s like we’re putting on our party hats and waiting to throw the doors open!

Everything about it has felt like a much more pure process, driven not only by mission but by genuine artistic response. We are choosing books to publish because we truly think they are incredible, choosing artists because we think their art is gorgeous. No one in this business can know what’s going to strike a chord; no one can prove which detail in the production values of a book is what’s going to make a difference to a book lover. It’s gut instinct and belief. And now, perhaps for the first time in my career, I can declare that that’s enough.

Daniel, a year from now, what kinds of thoughts and conversations among readers do you hope Everything Sad Is Untrue generates? What do you hope to hear from readers about the book?

Nayeri: There are a lot of people who speak for refugees, but not a lot of people who listen to them. I would love nothing more than to have young readers hear that term and think of Khosrou, someone they met in the course of reading the book, someone they may have come to like. To have a name that goes along with the word “refugee.” That would be powerful to me.

Nayeri: There are a lot of people who speak for refugees, but not a lot of people who listen to them. I would love nothing more than to have young readers hear that term and think of Khosrou, someone they met in the course of reading the book, someone they may have come to like. To have a name that goes along with the word “refugee.” That would be powerful to me.

Throughout the story, Khosrou makes this appeal to the reader. He says, we are here, in the parlor of your mind, and I am your guest. He is begging for the reader to see him as a guest and not an intruder. He wants the reader to hear him, and he struggles with the desire to listen to the readers, to hear their response.

If young readers could take in that idea, I think they might consider themselves as having a refugee friend. They might think better of them the next time someone uses the term in some fear-mongering political context, or even in a dismissive one. They will have sat with a refugee for hours, and they will have seen him bleed, and they might even want to welcome more of them into their lives.

Photo of Daniel Nayeri by Daniel Nayeri. Photo of Arthur A. Levine by Tess Thomas.

Wings of Ebony by J. Elle

Wings of Ebony by J. Elle Love Is a Revolution by Renée Watson

Love Is a Revolution by Renée Watson Game Changer by Neal Shusterman

Game Changer by Neal Shusterman Perfect on Paper by Sophie Gonzales

Perfect on Paper by Sophie Gonzales Lost in the Never Woods by Aiden Thomas

Lost in the Never Woods by Aiden Thomas The Cost of Knowing by Brittney Morris

The Cost of Knowing by Brittney Morris House of Hollow by Krystal Sutherland

House of Hollow by Krystal Sutherland Between Perfect and Real by Ray Stoeve

Between Perfect and Real by Ray Stoeve Realm Breaker by Victoria Aveyard

Realm Breaker by Victoria Aveyard Switch by A.S. King

Switch by A.S. King

Milo Imagines the World by

Milo Imagines the World by  Ancestor Approved edited by Cynthia Leitich Smith

Ancestor Approved edited by Cynthia Leitich Smith The Raconteur's Commonplace Book by

The Raconteur's Commonplace Book by  The Old Boat by Jarrett Pumphrey and Jerome Pumphrey

The Old Boat by Jarrett Pumphrey and Jerome Pumphrey Amber & Clay by

Amber & Clay by  The Tree in Me by

The Tree in Me by  Wonder Walkers by

Wonder Walkers by  War and Millie McGonigle by

War and Millie McGonigle by  Merci Suarez Can't Dance by

Merci Suarez Can't Dance by  The Rock From the Sky by

The Rock From the Sky by

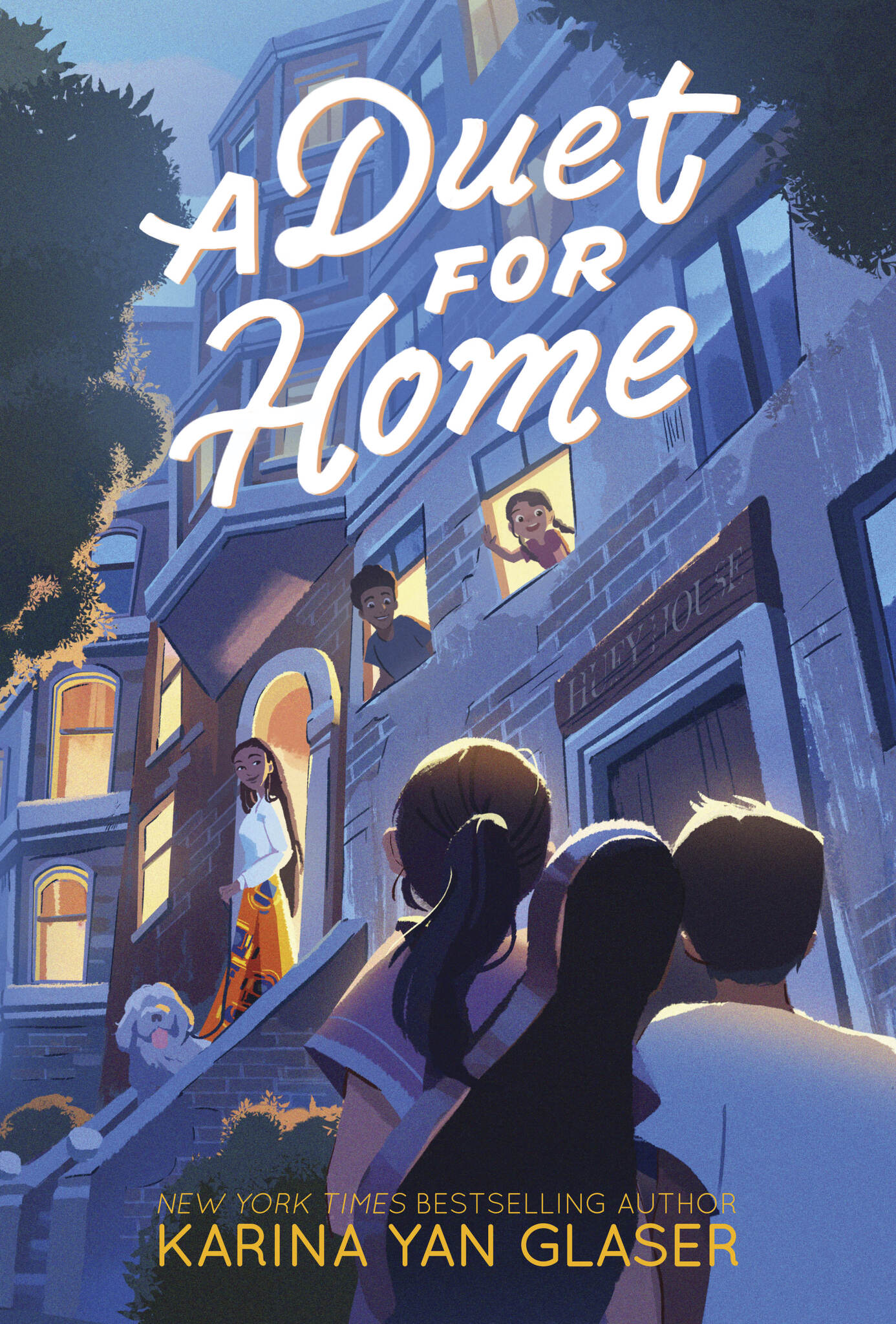

It's difficult to think of a recent fictional family more beloved than Karina Yan Glaser's Vanderbeekers of Harlem, New York, who burst onto the children's literature scene in the fall of 2017 in Glaser's bighearted debut,

It's difficult to think of a recent fictional family more beloved than Karina Yan Glaser's Vanderbeekers of Harlem, New York, who burst onto the children's literature scene in the fall of 2017 in Glaser's bighearted debut,

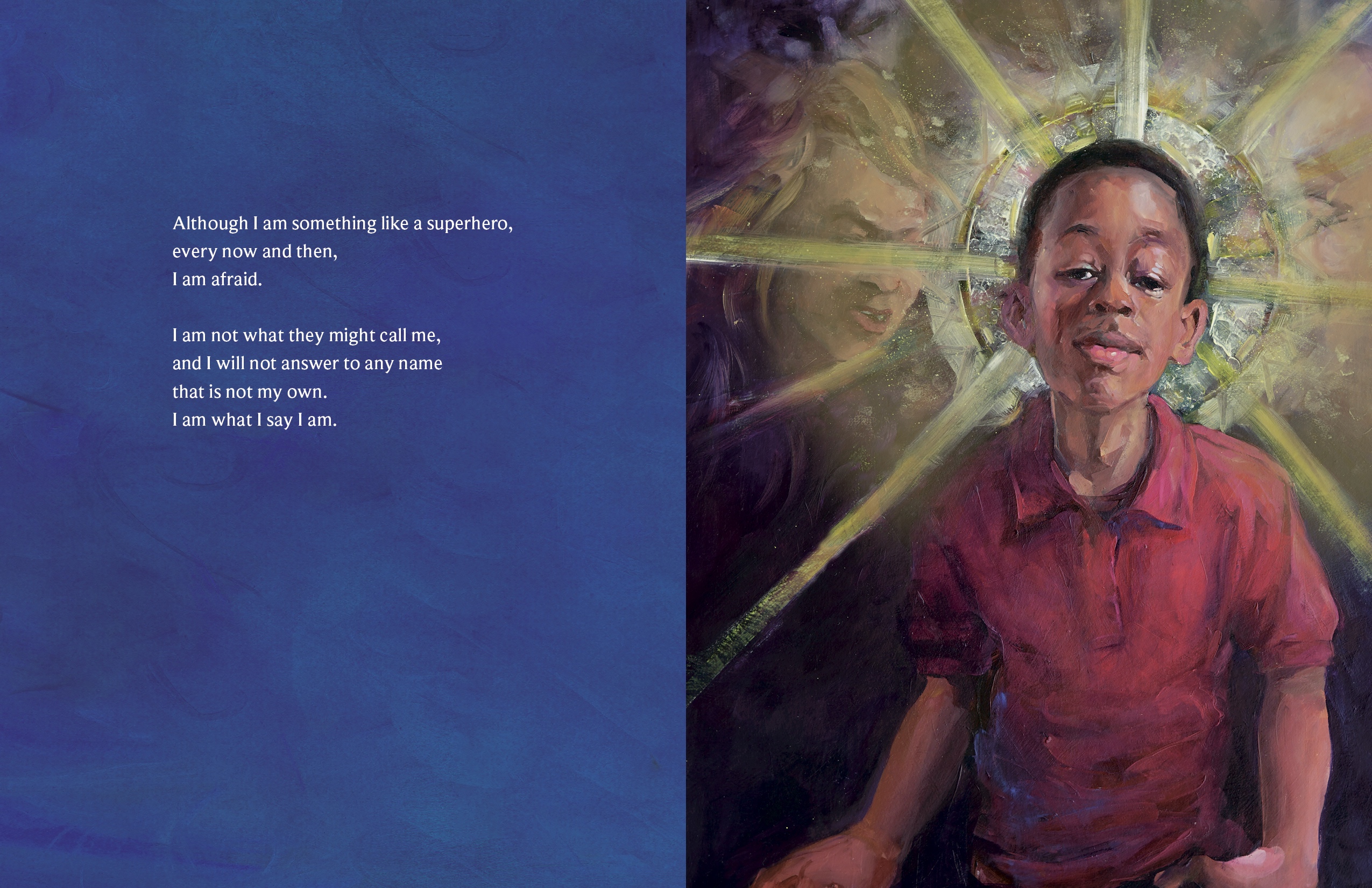

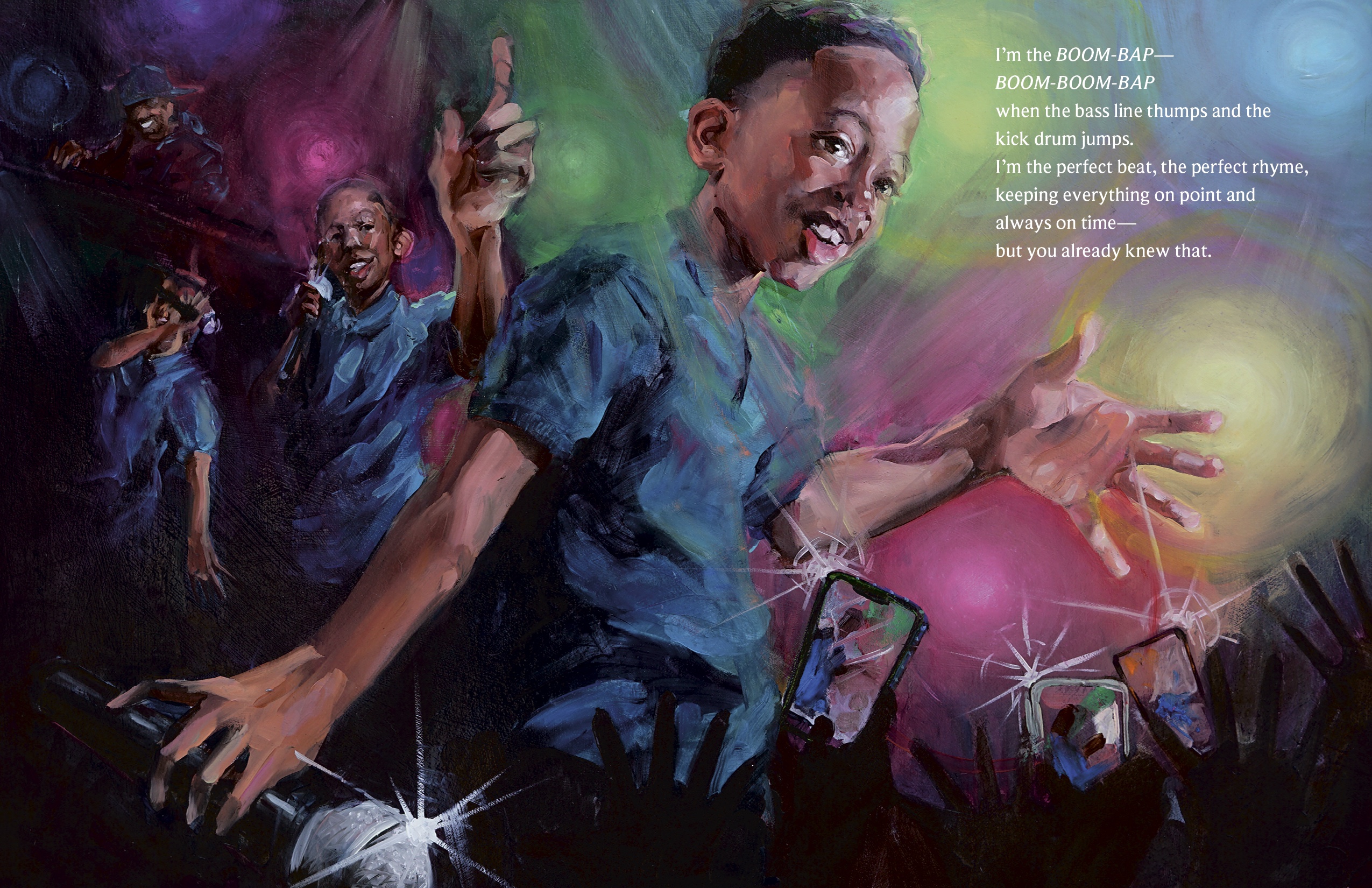

Barnes: The major difference was, when I wrote Crown, I didn’t even have a book deal, let alone an illustrator for the project. We went through at least three or four illustrators, who all turned it down. Gordon was meant to bring this story to life. There are no accidents in the universe. Our chemistry was still the same. We both agree on the message, the target audience and how much these affirming illustrations and words mean to Black and Brown boys.

Barnes: The major difference was, when I wrote Crown, I didn’t even have a book deal, let alone an illustrator for the project. We went through at least three or four illustrators, who all turned it down. Gordon was meant to bring this story to life. There are no accidents in the universe. Our chemistry was still the same. We both agree on the message, the target audience and how much these affirming illustrations and words mean to Black and Brown boys. James: After Crown, people were waiting to see what we’d do together next. How would it stack up? I was excited about the challenge to meet or even exceed those expectations. We still have the same personalities. We both want everything we create, together and separately, to be our best work. We want to leave a positive mark on our world.

James: After Crown, people were waiting to see what we’d do together next. How would it stack up? I was excited about the challenge to meet or even exceed those expectations. We still have the same personalities. We both want everything we create, together and separately, to be our best work. We want to leave a positive mark on our world.

Levine: I would strongly resist the characterization of the editor as a kind of G-d! At least in the traditional sense of an all-knowing, all-seeing, omnipotent being who shapes, controls and forms the book, with the author as clay. If you could meet Daniel, you'd laugh hard at the notion of me (or anyone) assuming that role with him!

Levine: I would strongly resist the characterization of the editor as a kind of G-d! At least in the traditional sense of an all-knowing, all-seeing, omnipotent being who shapes, controls and forms the book, with the author as clay. If you could meet Daniel, you'd laugh hard at the notion of me (or anyone) assuming that role with him! Nayeri: I like this. We’re going straight into religious conversation on question one. Leave it to you, Arthur, to get to the heart of the matter immediately. I have often heard from my fellow editors that the last taboo of children’s literature is religion. But this is a book about religion entirely. It is the reason the younger narrator is a refugee. Religion is the dividing line between his mother and father. And underneath his obsession with counting the memories of his grandfather is the anxiety that when they both die, they will go to different places. For me, G-d was in every word, or at least I hope so.

Nayeri: I like this. We’re going straight into religious conversation on question one. Leave it to you, Arthur, to get to the heart of the matter immediately. I have often heard from my fellow editors that the last taboo of children’s literature is religion. But this is a book about religion entirely. It is the reason the younger narrator is a refugee. Religion is the dividing line between his mother and father. And underneath his obsession with counting the memories of his grandfather is the anxiety that when they both die, they will go to different places. For me, G-d was in every word, or at least I hope so.

Cynthia Leitich Smith: Amazing books! Gorgeous books, heartfelt books, funny books, books with page-turning adventures and books with illustrations so gorgeous, you’ll want to linger over them. All lovingly created by Native authors and illustrators.

Cynthia Leitich Smith: Amazing books! Gorgeous books, heartfelt books, funny books, books with page-turning adventures and books with illustrations so gorgeous, you’ll want to linger over them. All lovingly created by Native authors and illustrators. Rosemary Brosnan: Cynthia wrote me an email in the fall of 2018, asking if I would be interested in working with her on a Native-focused imprint at HarperCollins. I jumped at the chance—and I’m happy to say that our President and Publisher, Suzanne Murphy, was on board immediately. I’m delighted that Cynthia thought of me for this wonderful venture.

Rosemary Brosnan: Cynthia wrote me an email in the fall of 2018, asking if I would be interested in working with her on a Native-focused imprint at HarperCollins. I jumped at the chance—and I’m happy to say that our President and Publisher, Suzanne Murphy, was on board immediately. I’m delighted that Cynthia thought of me for this wonderful venture.

Do you remember when you decided to become a children’s librarian? Did it feel like a decision or like an inevitability?

Do you remember when you decided to become a children’s librarian? Did it feel like a decision or like an inevitability?